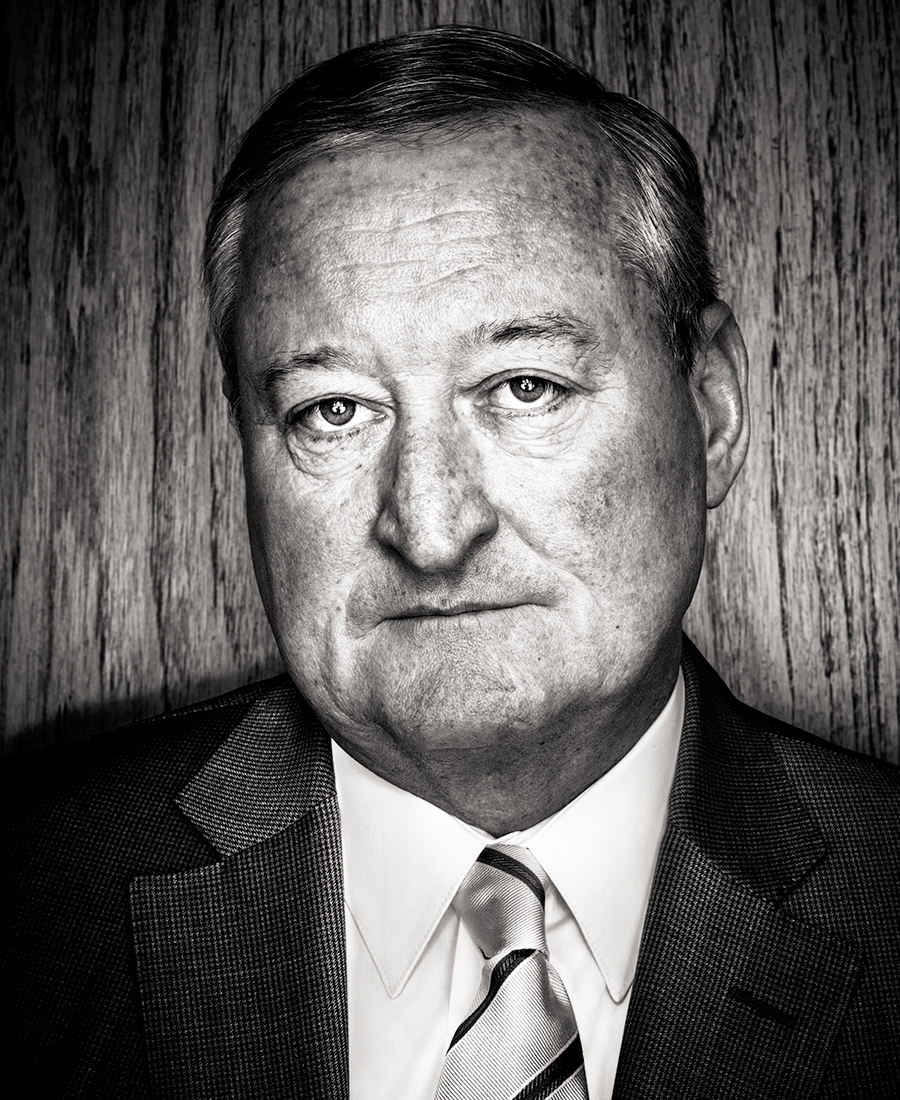

Jim Kenney Is the Most Ambitious Mayor Philly Has Ever Had. Why Doesn’t Anyone Know That?

What Mayor Kenney's aversion to the spotlight means for his agenda … and the city.

Photography by Dave Moser

A few hours into a day with Jim Kenney this fall, feeling a little desperate, I go to Lou Mfum-Mensah, an assistant who guides the Mayor through his schedule.

“Is he always so … silent?” I ask her.

In fact, he’s more than silent. Mayor Kenney seems morose. Unhappy. I’ve gone with him to a breakfast benefit for homelessness at the Loews, an outdoor press event in opioids-wracked Kensington, and the launch of a health-sciences partnership between Penn and Johnson & Johnson. That covers the Mayor’s morning, and as I sit two seats behind him in his SUV, or walk next to him at Kenney’s quick pace — “He basically fights the ground when he walks,” Mfum-Mensah says — I haven’t dared ask more than a nominal question or two about the weather or the Eagles.

In the SUV, Kenney, his small eyes and tiny mouth and great hooked nose making him look pinched, fiddles with the volume of sports-talker WIP and repeatedly checks his phone. Before going to the Kensington event, held to note the cleanup of heroin encampments, the Mayor asked another staffer exactly where they’d be meeting. “Kensington and Allegheny,” he was told.

“I love outdoor events,” Kenney said, sarcastically.

“Cleanups tend to be outdoors,” the staffer, apparently used to his moodiness, shot back.

On the way, Mfum-Mensah handed Kenney a three-page speech. “Why is it so long?” the Mayor said, reviewing it quickly before handing it back to her. She told him he was also scheduled for a radio interview about Kensington. No response. The Mayor seemed almost pissed.

“We try to keep it quiet,” Mfum-Mensah says about the atmosphere around the Mayor on the way to events. This is normal, in other words. But Kenney isn’t just quiet — he’s practically comatose.

A lot of people observing him now, including those who have known Kenney a long time, think he’s miserable as mayor. Frank DiCicco, a fellow South Philly neighborhood guy who got to know Kenney well in the ’80s when they both worked for then-state Senator Vince Fumo, sets the record straight: “He’s always been miserable.” DiCicco smiles — that’s Jimmy. I accompanied the Mayor a few days earlier on a visit to a pre-K classroom in North Philly, where he seemed quite comfortable chatting with three- and four-year-olds about their carrots and applesauce and then reading to them. When I remarked on how much he seemed to be enjoying himself, the Mayor said, “I love seeing the kids. It’s adults that are the problem.” It was the first thing he said to me.

But then today, just like that, everything shifts. I sit in the Mayor’s City Hall office midday while he devours a sandwich and flicks on MSNBC — “Let’s see what’s going on in this crazy world,” he says, suddenly sounding relaxed. And then he starts talking.

Kenney slips back, easily, to his past. His father (who passed away in early December at age 83) was a firefighter, and sometimes Jimmy would wake up early in the morning and smell the heavy, acrid scent of smoke; if his father had worked the night shift, it would be embedded in his clothes. The smell meant that his father was home.

He keeps talking. He’s Jimmy now, from Two Street — a regular guy bouncing from how much his Jesuit education at St. Joe’s Prep gave him to the baseball-bat murder of Chicken Arm Louie, his neighborhood’s heroin dealer, back in the late ’60s: “When his body was carried out, people cheered.” The Mayor has morphed into easy company.

Later today, however, the bad mood returns: After an event celebrating the opening of the Cherry Street Pier on the Delaware, it looks like the Mayor will leave too soon for the next obligation, honoring Boy Scouts at the Convention Center.

“If we get there early,” he complains, “people will want things. The longer we’re there, the more people want things. What are we going to do, sit in the car?”

Kenney’s crankiness isn’t just a problem for his staff; it’s a problem for the Mayor himself, and, moreover, the city. Three years into Jim Kenney’s tenure as mayor, as he gears up for a reelection run this spring, the conventional wisdom about him is pretty clear: Despite a handful of solid accomplishments, he’s failed to offer any kind of overarching vision for Philadelphia — or even much of a narrative about what he wants his mayorality to stand for. Ed Rendell famously overcame Philly’s fiscal woes and brought Center City roaring back to life. John Street cleaned up the neighborhoods. Michael Nutter struck a blow for clean government. But Kenney? He’s offered little in the way of inspiration, of getting people excited about what Philadelphia can be.

“No,” says Vince Fumo, when asked if his former protégé (they’re now estranged) is even capable of offering a vision. “That’s not the way he works.” He’s comfortable behind the scenes. A nuts-and-bolts guy, and not someone who can inspire: It’s a harsh but common critique of Kenney’s first term.

And yet the truth isn’t quite that simple. If you spend enough time around Jim Kenney and talk to the people closest to him, it becomes clear he does have a vision — an enormously bold one, in fact, that’s rooted in the progressive ideals that have gotten stronger as he’s gotten older: racial inclusiveness, support for immigrants, economic justice.

Mike DiBerardinis, the City Hall vet and Kenney’s managing director, claims one afternoon in his office that Kenney is the most ambitious mayor he’s ever worked for or been around — and DiBerardinis goes back to Rizzo. “There has not been such an aggressive agenda,” he says, since then. Yes, DiBerardinis is talking about his boss, but he doesn’t come off as pandering. (He’s also leaving for a post at Penn in January.)

At the center of almost everything for Kenney is education. “The biggest problem that we are facing is poverty in our city,” the Mayor tells me in his office. “The way out of poverty is education.” To Kenney, it’s patently obvious: If our lousy schools are the big thing holding the city back, then he has no choice but to take them on. To fix them.

It’s why the two biggest accomplishments of his first term — passing the soda tax to help fund universal pre-K and community schools, and taking control of the schools back from the state — have been focused on education. And it’s where Kenney himself sounds the boldest.

“It’s weird,” he says. “If you said to me, ‘Jim, it’s guaranteed you’ll pass the beverage tax to invest in schools but you’ll lose reelection,’ I’d still do it. If you’re not willing, why do this?”

That does reflect the kind of big ambition and deep conviction voters say they want in a politician. And yet Kenney is still plagued by the perception that he’s small, a City Councilman who climbed one rung too high on the ladder.

That view of him now goes to the heart of the tension in Kenney’s tenure as mayor: A strong vision — especially one as challenging as fixing our schools — needs a mayor out front, using the bully pulpit of his office to make so much noise about the importance of education that we can no longer ignore it.

But is Jim Kenney too grumpy and miserable — too fundamentally quiet — to give what he wants for his city a real chance?

Kenney is something of an accidental mayor, which is fitting, given that his entire political career has an air of reluctance about it. He came into the 2015 race late, sneaking up on us — if, that is, we were paying attention at all. It was a strange election, with candidates imploding: Tony Williams, the early front-runner, failed to sell his big issue, charter schools; Ken Trujillo got out for personal reasons; Lynne Abraham collapsed (literally, at a candidates’ debate). Kenney didn’t join the race until it was clear City Council President (and labor favorite) Darrell Clarke wasn’t running. An independent PAC with ties to union boss John Dougherty and South Jersey political honcho George Norcross raised nearly $1.5 million on Kenney’s behalf. He won the Democratic primary that May in a cakewalk.

Accepting Johnny Doc’s money gave Kenney a new financial overlord; Vince Fumo had been his first. Kenney and Fumo were an odd pairing, given Kenney’s St. Joe’s Prep brand of liberalism and Fumo’s hard-nosed politics. Kenney entered Fumo’s orbit at age 20, before he’d finished his political science degree at La Salle, and quickly moved up to become chief of staff in the state Senator’s Philly office, the man behind the man with the huge presence.

Today, in conversation, Kenney fends off the darker side of Fumo by claiming that as a staffer, he refused to do certain things — like tape a phone conversation with black activist and politician Charlie Bowser, which was illegal — and that he almost quit in protest a couple of times along the way. “It wasn’t as bad as it got,” Kenney says of Fumo’s shenanigans while he worked for him. “If it didn’t smell right, I didn’t do it.”

Kenney certainly wasn’t above some shenanigans himself. He and fellow Fumocrat DiCicco would listen to former mayor Frank Rizzo’s call-in radio show back in the ’80s because Fumo and Rizzo were mortal enemies and Fumo thought Rizzo might say something nasty about him that would be lawsuit-worthy; to relieve the boredom, DiCicco or Kenney would call in:

“Hey, Boss, this is Tony from Cherry Hill.”

“Tony, how are you?” Rizzo would beam.

“Boss, you were the greatest mayor Philadelphia ever had.”

“Thank you, Tony.”

“Boss, is it true that you were a bagman for the mob?”

Pause. “Why, I know who this is! I’m going to get you!”

With that, Kenney and DiCicco would be pounding the walls in hysterics, which, by the way, was a little fun on the taxpayers’ dime. In 1991, Fumo thought it was time for Kenney to be a Councilman, though he claims Kenney, tellingly, dithered. “Oh, all the fucking people who’ll come into the office like they come in here,” Fumo remembers him saying. “And I’ll have to deal with ward leaders.” (Kenney remembers the episode differently, claiming that he approached Fumo about running.) The Democratic Council slate was set without Kenney, but three weeks later, Fumo says, Kenney called him and had changed his mind; he wanted in. Both Fumo and Kenney agree, at any rate, that Fumo called Democratic boss Bob Brady, who kicked Bob Barnett off the ticket and installed Kenney; Fumo financed his campaign. Kenney was 32 years old.

An at-large Councilman has no constituency per se, so Kenney could take on issues, pound the table for things he cared about. Even early on, in the mid-’90s, Kenney supported liberal causes like gay rights; as he grew more progressive, the agenda became marijuana decriminalization and immigrant causes. Kenney seems embarrassed, now, over how he took on then-mayor John Street at every turn. “I wish I had done that differently,” he says. “I don’t think anyone on Council now has risen to the level of pain in the ass that I was to Street — you get a different view from here.” Nevertheless, he reveled then in being the hard-edged issues guy, fighting constantly with fellow Councilman Bill Green. He and Green sat at opposite ends of the horseshoe seating of Council, and Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, who sat next to Green, would lean forward to block their view of each other to calm things down between them. Kenney forged some level of independence; Ed Rendell, who got elected mayor the same time Kenney came to Council, says Kenney didn’t always do what Fumo wanted. He was learning to straddle the old and the new as he kept moving left.

Kenney and Fumo stopped talking because in Kenney’s view, Fumo forced his underlings to take the fall for him when he got in legal hot water; the two haven’t spoken for a decade. Now, Kenney pooh-poohs the idea that John Dougherty has a hands-on relationship with him: “He’ll send me a text, tell me to keep my head up, or he’ll call just to encourage me.”

Kenney ran for mayor at a time when belief and moment merged. While he was drawing on his own South Philly neighborhood past (even as he had rejected Fumo) and connecting with the unions, progressives, millennials, gays and immigrants, identity politics was taking over — a boon to Kenney. Bill Green says that Kenney is a very astute politician: “Jim is about slicing and dicing various constituencies to get a plurality in order to get elected … the bike people, sanctuary cities. Education is very important to a large segment. Here’s a group of people passionate on their issue, and he’ll be that issue, so they transfer their passion to him and become members of his army.” Which is the real takeaway from Kenney’s Fumo years — a political savvy he got by osmosis. Still, Green takes the same shot at Kenney that many others do: “In terms of having a big picture for the city, I don’t see it.” At any rate, the salt-of-the-earth guy who cares deeply played well and got Kenney elected.

His evolving progressiveness isn’t the only thing that’s changed since Kenney first emerged on the political stage. He no longer lives in South Philly — the Mayor has an apartment in Old City now, and there’s strong resentment among some people that he’s forgotten where he came from, which, in turn, ignites the Mayor’s hair-trigger defensiveness.

“I’m in South Philly a lot,” he says in his office. “This whole idea, ‘He forgot where he came from’ — I didn’t forget where I came from. All the things that drive me are because of where I came from. The fact that I won’t jump a line at a funeral parlor or viewing. I won’t jump ahead of people because I’m mayor. Most if not all of what I learned or experienced growing up in South Philly, I still maintain. I love Italian food and culture. Because I don’t like the Frank Rizzo statue or thought Columbus was not a good guy doesn’t mean I don’t appreciate Pavarotti or Enrico Fermi or you name it.”

Kenney’s got another hair trigger, for social justice — especially racial justice — and he segues to it like it’s a calling.

“People who grew up in the Rizzo era,” the Mayor says, “especially people of color, don’t want to have to pay their real estate bill or water bill [at the Municipal Services Building on JFK Boulevard] and have to look up at him going in there every day. He represented something to them that was bad.”

Kenney says he decompresses these days by going to New York — walking around, seeing a show. “I can be anonymous there, on a spring weekend. … ” People in Philly who stop him on the street are fine for the most part, he says, though he runs into some who want to have at him. “It’s white men. They’re all Trumped up. I gotta be me. I can’t stand that racist, misogynist, negative crap. I say to people sometimes, ‘You’re white, you got a house, a house at the Shore, you got two cars, wife is working, nobody is shooting your kids, what are you so angry about? You should be the happiest guy in the world. Why are you so angry?’

“It’s all race. The country is changing, evolving, becoming more people of color. They feel outnumbered and scared. Now they know what Native Americans felt. Make America Great Again — what, are we going to make the country Cherokee? They seem to forget that. The white privilege, it’s embarrassing to me, and aggravating.”

Mayor Kenney might seem an odd poster boy for identity politics, but that’s where he’s landed. What’s in question is how much of his progressive agenda he can pull off, and how. Ed Rendell always said: “Being mayor makes you larger or smaller.” School is still out on Jimmy from Two Street.

Mark Squilla, the Councilman to whom Kenney is probably closest, says Kenney always wanted to be mayor. And Kenney claims he knew what the job of mayor would be like, from the 23 years he served on City Council. “But sometimes it’s overwhelming,” Squilla says. Which sounds like the job is harder than Kenney thought it would be.

“I think that might be true,” Squilla says. “He never wanted to be in the public forefront, onstage, ‘I am the leader.’ That’s not his personality. He’d rather be behind the scenes, getting things done.”

You leap onto a fast-turning wheel, you hang on for dear life, especially if you’re the accidental mayor. When I speak to him, former mayor Wilson Goode claims he never slept well when he held the job — never reached a deep dream state in eight years. Kenney says he stopped sleeping well a decade ago, at 50 — “a metabolic thing.” He sometimes winds down after work at the Race Street Cafe, having a drink alone, and later roams the late-night talkers: Colbert, Kimmel, Fallon, back and forth, then to bed. He lives alone; his son and daughter are adults now, and Kenney, separated for years from his wife, is going through a divorce. Kenney claims that he has time to think; he acts as if he can’t move fast enough. And God knows, in the job of mayor, things will be thrown at you. Goode is living testament to that, the MOVE disaster the millstone he’ll drag to the first line of his obituary.

Kenney’s big test to date has been different, a growing horror: In 2017, there were more than 1,000 deaths from opioid overdoses in the city, Philadelphia’s worst public-health crisis in a century.

Quiñones-Sánchez and Squilla, the two Council members whose districts include parts of Kensington, were immensely frustrated with the response of Kenney’s administration. As the new heroin encampments under railroad bridges grew, residents railed about needles everywhere, addicts defecating in their flower boxes, their community essentially being taken over. Squilla says he repeatedly went to Kenney and his people, begging them to act. Kenney tends to give his underlings a long leash, and the administration seemed overly concerned with lawsuits from the ACLU if they got too aggressive in arresting addicts or forcing them into treatment. “The city wanted to make sure the I’s were dotted and T’s crossed,” Squilla says. “Sometimes, you have to just do something and get sued anyway, because when we go to those meetings, those residents, by right, are furious.”

“I want Councilman Kenney,” Quiñones-Sánchez told the Mayor — the one who would pound tables and pick fights with Bill Green and Mayor Street and demand action.

“I’ve got a whole city to run, Maria,” the Mayor responded.

“We’ve never sat in a room,” Quiñones-Sánchez says, “where we’ve debated this issue, where I can challenge his people in front of him. His people won’t let that happen.”

Kenney disputes that, saying he’s partnered with Quiñones-Sánchez. Certainly, though, there has been much foot-dragging on the epidemic, and a dearth of creative thinking. The Mayor is in favor of establishing safe injection sites, which is Kenney out on a limb, a progressive’s progressive, like fighting ICE. But will it fly? For both legal and political reasons, the answer is almost certainly no.

By last summer, there were some 700 addicts living on the streets of Kensington.

It feels a little too easy — and perhaps it’s also slightly simplistic — to track the mistakes of Kenney’s administration in dealing with the opioid crisis in Kensington as if a much better result should have been at hand. It’s a complicated problem; Kensington has been a marketplace for various drugs for half a century. But the one avenue a mayor surely does have — to get before us and rouse our understanding and feeling — Kenney has mostly taken a pass on.

In October, for example, when Kenney announced he was declaring the opioid epidemic a disaster and calling on his administration to find a new approach in addressing it, he put on his reading glasses and barely looked up at a row of cameras at the Emergency Operations Center on Spring Garden Street. “It truly breaks our hearts to think about what [addicts] are experiencing,” he said, moving quickly through prepared remarks. This was not a sentiment that could be convincingly read, much less speed-read. “Parks are littered with human waste, needles, and illegal activity,” he continued. “I’ve said many times before — there are no throwaway people.” But he sounded like he was talking about tax reform.

What’s ironic is that it’s abundantly clear, when you spend time with Kenney, that what he sees in Kensington does touch him — he says it’s heartbreaking. But just when we need Ed Rendell, we’re getting Calvin Coolidge.

Yet it’s also not a matter of inability; when he speaks unscripted, a different Kenney begins to come through. On the day I go with him to Kensington, instead of reading the prepared remarks his assistant hands him in the car, he folds them up, keeps his glasses in his pocket, and simply … speaks. “We need to deal with folks who are here who are suffering, both the people who are addicted and the people living with the people addicted. And unlike the ’80s and ’90s, locking our way out of this did not work then during the crack epidemic, and it will not work now. We … need to understand why people get in the situation they’re in and unwind their lives to get back to normal. … This neighborhood has not only suffered the most, living with this terrible plague” — with that, an ambulance siren, so common in Kensington, almost drowns him out — “it has given the most. We understand that living with this is difficult.”

Simple, heartfelt, real — it wasn’t Barack Obama, but it was Jim Kenney. He says he doesn’t like to speak unscripted because he tends to ramble, and at the end of this short speech, he does tack on an off-point shot about the NRA really working for gun manufacturers on the backs of poor people. But the Mayor would be a lot better off if he threw away his reading glasses and trusted his instincts before crowds.

One other thing: Kenney is promising a lot in the city’s newfound commitment to Kensington. There are two ways to take that. One, he’s a politician. But it also resonates with what managing director Mike DiBerardinis said — that Mayor Kenney really is up to something.

“They call me ‘Snowflake,’” Jim Kenney says — that is, a softy ready to take on any left-leaning social issue. “But if people don’t want me to lead the city in making an investment in education, good luck.” (Kenney gives Rendell the nod as the best Philly mayor of his lifetime, but he can’t resist taking a shot at how Rendell felt education was too risky to take on: “Rendell should have tackled schools his second term.”)

Once he gets rolling as he talks about education, Kenney is as adamant as he can be pinched and silent and miserable. “There’s no magic potion,” he says. “People are constantly saying we’re wrong to take it on — they’re basically saying our kids can’t learn. That’s abhorrent. I see kids as perfect, until a certain age, and then we’ve lost them. I don’t want to lose any more.”

He’s passionate, certainly. The problem is that we’re talking privately in his office, where he slaps his table for emphasis. I challenge him on his public stance — on whether he might agree that it should be bigger. He doesn’t seem to understand: “I talk about education every chance I get.”

And of course, it’s not just talk. Kenney pushed through that tax on soda to fund a pre-K program as well as community schools, intended to help students with problems stemming from poverty, such as nutrition and mental-health issues. And he took over control of the school system from the state. (The school reform commission was disbanded, and a new board, appointed by the Mayor, convened in July.)

All of that is politically brave. The possibility of failure is strong, and Kenney will certainly see no benefits from pre-K during his tenure. But there are plenty of studies that show if a student is reading below grade level by the fourth grade, bad trouble looms.

Not everyone thinks Kenney is doing enough, however. Longtime education advocate and former SRC member Sylvia Simms and a second former SRC member say that the Kenney administration’s attitude seems to be: Okay, we’ve checked off the boxes, as promised, on city governance and pre-K and community schools, so that’s that.

Kenney disputes that critique: “We have integrated virtually every city department into the school system. We had a tragic accident when a school boiler blew up. And within a week, L&I and a private plumber were inspecting every boiler in the city. We coordinated all that. I don’t understand that criticism.”

The critics’ point, given Kenney’s lofty goals for the schools, goes deeper: The Mayor needs to be more public in his support of Superintendent Bill Hite; to go to Harrisburg to partner with Governor Wolf and Secretary of Education Pedro Rivera to fund programs like STEM, to get students better trained in technology; to push for more charter-school oversight and the right-sizing of schools.

Regarding Hite, Kenney says he’s with him all the time. Isn’t that good enough? And regarding Harrisburg, “Me walking around, banging my head on doors there — at some point, your head gets hurt.”

He’s right — going to Harrisburg with hat in hand and simply begging for money won’t fly. But maybe pushing for some help with new initiatives in the offing could.

Former mayor John Street has another idea. If Jim Kenney really wants to take on education, Street says, “I think what I would do is have a huge education summit, across the Commonwealth and country. We’re spending $3 billion a year — how much should we be spending? You can’t create a vision for public education, and pretend to do what needs to be done, on current resources. He should look at all existing programs, look around the country. I would have said to Gerry Lenfest, ‘Talk to foundations; see if you can raise $10 million.’ Then report out a huge plan for public scrutiny.”

Bill Hite likes the idea of using the local brainpower that was gathered to pitch Amazon headquarters coming to Philly — in fact, when I suggest it, he says he’ll text the Mayor about gathering those movers and shakers together to talk education.

You can see where this is going — everyone, even a journalist, is an expert. The Mayor sees it, too. I run Street’s idea by him — to have a huge education summit in search of the best ideas — and Kenney says, “Given the urgency of it, I couldn’t sit back and study education to death. I wanted Dr. Hite to continue and accelerate what he was doing, and I told him if he left, I’d hunt him down.” But Kenney might be missing the point: Perhaps an education summit would yield nothing concrete yet plant the idea of how vital it is to improve the schools in the minds of Philadelphia’s white middle class, which needs to buy in for Kenney to pass a likely rise in taxes to fund improvements. But at heart, Kenney isn’t a thinker or a cheerleader. He wants to move the boulder up the hill, not stand on top rallying the masses.

It is, of course, a very heavy boulder, especially here. Hite says other cities have a much stronger commitment from the business community to help. Sandra Dungee Glenn, a former head of the SRC, believes we need to press Penn and other city colleges to contribute their fair share, to engage more with schools and students. On my day trailing the Mayor, when we go to a feel-good event at Penn to celebrate the partnering of Johnson & Johnson with the Pennovation tech center, I can’t help thinking: Here’s your real audience, Mayor. Kenney insists that the inner city hears him and feels his commitment, but that’s an easy sell. Kenney hugged Penn president Amy Gutmann. That’s who needs to buy his message.

Wilson Goode believes quite strongly in Jim Kenney, to the point that the former mayor says, “He may end up — forgive me, Ed — getting more concrete things done than Ed Rendell did.” But Goode, too, circles back to Kenney’s mayoral footprint and wants more. “I think to be an education mayor, you need to call upon foundations, call upon universities in the city, call upon state government, call upon the federal government, make major speeches about how important education is, write letters, use his lobbyists to get every cent he can for the school district.”

To use his bully pulpit, in other words, aggressively. But Goode isn’t sure Mayor Kenney is comfortable with being that loud — with going, say, to the U.S. Conference of Mayors and laying out the education crisis here, which would in turn put more pressure on the city.

“But all he has to do is decide he’s going to do it,” Goode says.

Ed Rendell, loath to criticize the Mayor, does say: “The only thing I’d change about Jimmy is that he should, and you can say this about any of us who held office, be less sensitive to criticism — let more of it roll off his back.” Occasionally, Kenney has lashed out at Rendell — when the ex-mayor was quoted in the press opining that Kenney had scheduled the Eagles’ Super Bowl parade on the wrong day, for example.

Kenney called him. When Rendell answered, Kenney said, “Oh, so your phone is working.” It went downhill from there.

“But I don’t take it personally,” Rendell says, and then he thinks of something else he would change about Kenney: “It sort of goes hand-in-glove with the other — to have a little more fun on the job.”

Maybe Jim Kenney can’t help himself. He often still seems like the fifth-grader whose teacher, a nun, called his mother in for a conference. Not because Jimmy was doing badly in school, or was misbehaving. The nun told his mother that she called her in because everything Jimmy thought came out on his face, and she couldn’t stand it.

Kenney himself doesn’t exactly deny his own grumpiness, or even some unhappiness in City Hall: “There are aspects to the job I don’t like.”

Meaning the public parts. Which is a shame, not just for the city, but for the Mayor, too: That take-no-prisoners moral purpose he breaks out in private would certainly be useful to him if he showed it publicly, as he did for a moment when he went off-script in Kensington on the day I spent with him and spoke his mind. That would help him, and perhaps us, a great deal. Because there’s no doubt that the Mayor, once you spend a little time around him, really is invested mightily in the state of his city.

Jim Kenney will never be Ed Rendell. When Rendell was no longer governor, he said over and over that it wasn’t the same being out of office. There wasn’t enough action, no wall-to-wall stuff to worry about, nobody clamoring for him. Jim Kenney, on the other hand, will have no problem stepping away from public life. At this point, he’d have to fail outrageously not to get reelected to a second term, but after that, he says, “I can see myself teaching. I would teach high school or grade school. The classroom environment actually makes me feel good.” Children, after all, are much better than adults.

Published as “Jim Kenney Is the Most Ambitious Mayor Philly Has Ever Had.” in the January 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.