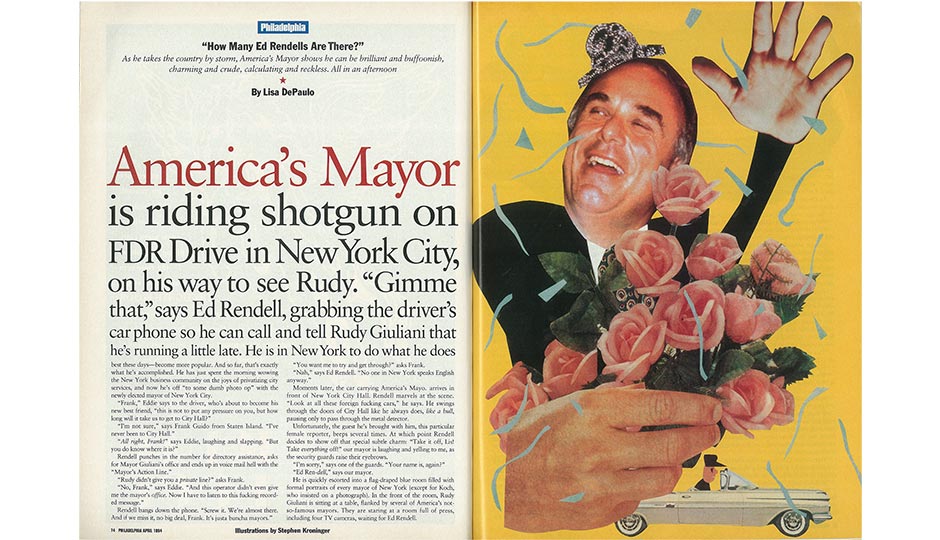

“How Many Ed Rendells Are There?”

The opening spread of “How Many Ed Rendells Are There?,” from the April 1994 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

In “How Many Ed Rendells Are There?” (April 1994), Lisa DePaulo masterfully dissected the glowing national reputation of our then-mayor — and found herself splashed across the Philly papers for reporting Fast Eddie’s salacious comments to her. “My favorite was the Daily News cover LADY IN RED, because the day the story broke, I was wearing a red suit and sitting at my desk behind a vase of red roses — sent by Zack Stalberg, the editor of the Daily News,” DePaulo recalls. “I gotta hand it to Zack. That was brilliant PR.” Rendell held a press conference to address the brouhaha. But while he fessed up to a “salty, earthy” sense of humor, he added that DePaulo “gave as good as she got.” Still, he added, “I feel a little stupid.”

America’s Mayor is riding shotgun on FDR Drive in New York City, on his way to see Rudy. Gimme that, says Ed Rendell, grabbing the driver’s car phone so he can call and tell Rudy Giuliani that he’s running a little late. He is in New York to do what he does best these days – become more popular. And so far, that’s exactly what he’s accomplished. He has just spent the morning wowing the New York business community on the joys of privatizing city services, and now he’s off “to some dumb photo op” with the newly elected mayor of New York City.

“Frank,” Eddie says to the driver, who’s about to become his new best friend, “this is not to put any pressure on you, but how long will it take us to get to City Hall?”

“I’m not sure,” says Frank Guido from Staten Island. “I’ve never been to City Hall.”

“All right, Frank!” says Eddie, laughing and slapping. “But you do know where it is?”

Rendell punches in the number for directory assistance, asks for Mayor Giuliani’s office and ends up in voice mail hell with the “Mayor’s Action Line.”

“Rudy didn’t give you a private line?” asks Frank.

“No, Frank,” says Eddie. “And this operator didn’t even give me the mayor’s office. Now I have to listen to this fucking recorded message.”

Rendell bangs down the phone. “Screw it. We’re almost there. And if we miss it, no big deal, Frank. It’s justa buncha mayors.”

“You want me to try and get through?” asks Frank.

“Nah,” says Ed Rendell. “No one in New York speaks English anyway.” Moments later, the car carrying America’s Mayor arrives in front of New York City Hall. Rendell marvels at the scene. “Look at all these foreign fucking cars,” he says. He swings through the doors of City Hall like he always does, like a bull, pausing only to pass through the metal detector.

Unfortunately, the guest he’s brought with him, this particular female reporter, beeps several times. At which point Rendell decides to show off that special subtle charm: “Take it off, Lis! Take everything off!” our mayor is laughing and yelling to me, as the security guards raise their eyebrows.

“I’m sorry,” says one of the guards. “Your name is, again?”

“Ed Ren-dell,” says our mayor.

He is quickly escorted into a flag-draped blue room filled with formal portraits of every mayor of New York (except for Koch, who insisted on a photograph). In the front of the room, Rudy Giuliani is sitting at a table, flanked by several of America’s not-so-famous mayors. They are staring at a room full of press, including four TV cameras, waiting for Ed Rendell.

It turns out this is not just a dumb photo op.

“Glad they told me,” mutters Rendell, who had “no idea” that Rudy gathered them here, in view of the entire New York press corps, to draft a letter to President Clinton to beg for more cops for the cities.

Rudy is sitting with his hands strangely clenched together, his mouth a thin straight line, in a crisp white shirt and cufflinks, white silk hankie in the pocket. When he spots Rendell barreling through the door, he bares his teeth. That’s the way Rudy smiles.

Then what does our fine mayor do? Well, he does what he always does. He knocks their socks off.

First he waits, occasionally making faces, while the other mayors from towns like Houston and Indianapolis take their turns speaking. Then he smoothly adlibs the best and most sensible sound bites of the session. When it’s over the New York press has questions — almost all of them for Philadelphia’s mayor. One reporter decides to challenge him. “At a breakfast here a few weeks ago,” s reminds him, “you said you didn’t want more cops … “

“First of all,” says Eddie, “we’ll take anything we can get.” Laughter. So, yeah, he’ll sign the letter, but “you’re right,” he tells her, more cops isn’t the first thing on his wish list from Washington. “Because in the long run, all the cops in the world will do no good if we don’t get our people back to work … “

As always, his answers begin as ad-libs and end up like campaign speeches. “Because if we don’t, we’ll just have armed camps.”

The press nods and scribbles. Rudy bares his teeth. They love him.

Afterward Rudy lets the other mayors leave, then invites Rendell back to his office.

Giuliani invoked Rendell’s name all through his messy campaign — promising New Yorkers that he would do for their city “what Ed Rendell did for Philadelphia.” The line got Rudy his biggest applause. He said it so many times that Ed’s relatives in New York, where he was born, would call him up after watching the news and say, “He mentioned you again.”

Giuliani’s opponent, David Dinkins, managed to squeeze a sort-of statement of endorsement out of fellow Dem Rendell, literally on the eve of the election. “Because I think he’s one of the finest individuals I ever met in politics,” says Eddie. “But I agreed with Giuliani on most of the issues.” And it was Giuliani who literally the day after the election, had his staff make one of their first calls to Ed Rendell — asking “for all of our written stuff” (the five-year plan, etc.).

“This was LaGuardia’s desk,” says Rudy, proudly showing it off as Eddie rubs fat fist across the surface.

“No kidding,” says Rendell.

“When you were born,” says Rudy, beaming, “he was mayor of New York.”

“So,” says Ed, “where’s your real office?” Giuliani smiles, this time a real one.

“You want to see it?” he says eagerly.

He leads Rendell out of the fancy ceremonial office, through a small kitchen and down a narrow flight of wood stairs to a room that could pass for an office in an insurance agency: mini-blinds, ceiling fan, industrial carpet, glass shelves — empty except for a few framed family pictures. In office two and a half weeks, Rudy is still unpacking boxes.

“This is where Dinkins and Koch worked too,” says Rudy.

Rendell checks it out, peering through the blinds. “So this is actually on the first floor,” he observes. “Ya paranoid?”

“Well, not really,” mutters Rudy.

“Good,” says Rendell. “You shouldn’t be. Before I got elected, the Philadelphia mayor’s office was like a bomb shelter. And like I told my staff: ‘If somebody’s gonna shoot me, they’re not gonna do it through my office window.”’

Rudy chuckles with him, though his eyes dart to the windows a bit nervously.

“So,” says Rendell, slapping him on the shoulder. “How does it feel?”

“It feels great,” says Rudy, awkwardly returning the slap. “It’s a great job. You know that.”

“Yeah,” says Rendell. “And you’re doing a great job, Rudy. You’ve been mayor for two weeks and the Rangers are already headed for their first Stanley Cup!”

As he says goodbye, Rendell promises Giuliani what he’s promised every group he’s spoken to in New York. That the mayor of Philadelphia — and who would have believed these words just a few years ago? — will continue to help New York in any way he can.

As he leaves New York City Hall, he stops to talk to a janitor, then playfully slaps the guy at the metal detector. “Don’t worry,” says Ed. “She didn’t kill him.”

“So,” says Frank, as America’s Mayor tumbles back into the car. “How’d it go?”

Rendell considers all the possible Giuliani stories he could share with Frank Guido from Staten Island, then picks this:

“Lis must have a spiked metal bra on or something, ’cause we almost didn’t get in,” he says, laughing.

“So how was Rudy?” Frank wants to know.

Rendell tells him how he wasn’t expecting a press conference.

“So ya got duped,” says Frank.

Rendell laughs. “Rudy’s a good guy,” he says. “And I think he’ll build an effective coalition. Because New Yorkers are smart people, Frank, and they know they’re up shits creek.”

“I don’t know about Giuliani,” says Frank.

“Yeah,” says Eddie. “We told him you didn’t like him.”

“Oh, man.”

“Yep. Gave him your plates and everything.”

They both crack up. And so it went — with no surprise that our Ed Rendell would bond as easily with Frank Guido as with Rudy Giuliani. That’s part of what makes him so effective: The man has broad tastes indeed.

In the 24 hours I spent with Ed Rendell in late January, I watched him charm three groups of jaded New Yorkers, invite Frank the driver to join him at a game if the Phillies make the World Series this year, eat a hot dog in two bites, deliver a speech so eloquent audible “wows” could be heard, and speculate on how I might be in bed.

America, meet your mayor.

OF COURSE, THIS PARTICULAR trip to New York was just one blip on his radar screen of “personal appearances.” Since Ed Rendell became a national sensation, he’s been logging more miles than the average Miss America — all to spread the good word of how he rescued Philadelphia from financial and moral despair, and how you too can make your city great.

Why, he’s even starting to talk like a Miss America.

“One day in October,” he tells me, “I had to be in Albany for some ‘restructuring government’ thing. My presentation was over at 9:50 a.m. I hopped a 10:10 flight to Phoenix to speak at a panel for the Association of Transit Administrators — you know, streets department people, stuff like that. I got finished at 2 Phoenix time, then I had to speak again in Phoenix, then I took a red-eye back to Philly. I got in the middle of the night.”

Since he took office 15 months ago, he’s been traveling to other cities, by his own estimation, three times a month; is a regular visitor at the White House; and is currently being booked three months in advance. He’s been everywhere from Reno to Dallas. Mayors conferences alone — where he is invariably a speaker — have eaten up four trips. He’s in Cambridge giving pointers to 44 first-time mayors at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. He’s in New York — and later, the New Yorker — to deliver the prestigious Wriston Lecture. He’s in D.I dazzle the cynical Washington Press Club.

And rarely does a day go by when some other mayor, or some other “reinventing government” disciple, isn’t on the phone with him asking for more advice. He’s particularly chummy with Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago and Mayor Kurt Schmoke of Baltimore, both of whom are his age and, like him, former prosecutors. Schmoke, who’s a big fan of Ed’s, says he and Rendell “have stolen so many ideas from one another that we don’t remember who thought them up first. We talk about everything from law enforcement to federal housing policy. We [also] talk a great deal about baseball.” Schmoke says Rendell likes to “remind me of my lack of clout in my own city.” Turns out, when Schmoke was the state’s attorney of Baltimore, he had to call Ed Rendell in Philadelphia to get tickets to a World Series game between the Orioles and the Phillies — at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore.

When L.A.’s Republican mayor, Richard Riordan, got elected, he flew to Philadelphia the following week — to get four hours of tips from Ed and chief of staff David Cohen. When Dennis Archer, the new Democratic mayor of Detroit, got elected, he flew to Boston — to pump Ed outside class at the Kennedy School. That Rendell is also every mayor’s direct line to Bill Clinton — “We’ve become great friends,” says Ed — hasn’t hurt his stature either.

But it was really the press — the national press-that launched the Rendell Cross — Country Tour. The mayor says he wasn’t surprised at all when he became the flavor of the month. Or rather, 15 months. “Because this is a faddish country,” he says, “I knew that once the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal wrote a story about us, everyone would do a story about us.”

Since then he’s had his ass kissed in every media outlet from the CBS Evening News (“I hear Philadelphia is a great place to live, John,” says the CBS anchor to the CBS reporter) to the Las Vegas Review-Journal. It has gotten so that the gushing he receives almost daily in the Inquirer and the Daily News seems like criticism compared to what the rest of America thinks.

“He’s even been in our limelight in Oregon,” as Portland’s former Mayor Neil Goldschmidt put it, introducing Rendell to yet another fawning group of New Yorkers. “He has taken a fresh look at how we are doing everything in our ties.”

Naturally it was only a matter of time before the rest of America would want to meet this Ed Rendell. “I get tons of invitations,” he says, “and I turn down a ton. All because of the success of what we’ve done in Philadelphia.”

Oh, right. Philadelphia.

No one can argue that Eddie’s national exposure hasn’t done wonders for the city’s image-when was the last time a hotel doorman in New York said, “You’re from Philadelphia? Wow. I hear it’s a really nice place.”

But as Rendell himself is the first to admit, there’s still some work left to do around here. Yeah, he’s balanced the budget, turned the deficit into a surplus, boosted the bond rating, strong armed the union workers and landed a part in the Philadelphia movie. But ours is still a city that is losing 2 percent of its jobs each year, we just had the biggest population loss of any major city, and while Center City’s shining (almost), the worst neighborhoods have only gotten worse. Unfortunately, solving the whole urban crisis is not a ceremonial job.

Eddie likes to point out all the gigs he’s turned down (“Ten for every one that I accept”). Yeah, he went to the White House to screen Philadelphia with the president and director Jonathan Demme. Yeah, he’s had a roll in the Lincoln Bedroom. But when his new pal Bill invited him down to schmooze with Arafat and Rabin after “the handshake that shook the world,” he turned it down. Some small business was opening in Philadelphia. And yeah, The Donald is another new pal — they have regular conversations about riverboat gambling, says Ed, and Trump does little favors for him, like promising to fly in Muhammad Ali and his family and pay all their expenses so Ali can appear at “Knockout Night” during our Welcome America party in July. But Eddie turned don an invitation to Donald and Marla’s wedding: “It was our office party that night.”

“The glamour part of it really doesn’t do it for me,” Eddie insists. “Really I get a bigger kick out of that middle-aged man coming up and asking for an autograph for his mother,” referring to one of the many fans who assaulted him at the train station, “than reading in the Picayune Times that I’m America’s Mayor.

“And, well, one of the reasons is I do try to work. So I really limit my traveling. I mean, if I really wanted to whack off, I could be out of town five days a week.

Of course, he also has two valuable weapons. The first is David Cohen. Here in Philadelphia, it’s become a joke that the man behind the curtain, the guy who never leaves town and rarely even leaves City Hall, is Eddie’s chief of staff, the 38-year-old former Ballard Spahr partner who left a big-bucks law career to be Rendell’s Boy Friday (through Thursday). Now, even the other mayors are starting to catch on. Eddie reveals that Richard Riordan, who has some personal wealth, “told David, ‘If you come to L.A., I’ll pay you $350,000 out of my own pocket.’“ Cohen, who makes $90,500 in Philadelphia, turned it down.

Rendell laughs when he tells the story. “If he’d have asked me, I’d have gone.”

His other weapon is his seeming ability to be everywhere. It’s hard to imagine that he spends so much time in hotel rooms when his mug appears all over town — more often than not making all four news channels a night for his city-wide appearances. In fact, he’s been such a ubiquitous presence around the city he claims to have rescued that, as one Philadelphian put it at a cocktail party moments after seeing Ed at another cocktail party, “How many Ed Rendells are there?”

There’s Ed at Wanamaker’s for a fashion show. There’s Ed taking drink orders in a waiter’s uniform at the Palm for some charity event. There’s Ed under the flash-bulbs at the reopening of New Market, as Society Hill residents line the sidewalks to get a glimpse. There’s Ed feeding strawberries into the pouty mouths of Katmandu waitresses at a photo shoot for this magazine. There’s Ed conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra before game four of the World Series He jumps in pools, he cleans toilets, he cooks hot dogs outside City Hall, he stands on Gay News publisher Mark Segal’s roof at midnight during a Christmas party and sings “Happy Birthday” to his secretary.

On an average day in Philadelphia, says Eddie — who claims to survive on four hours of sleep a night, “five tops” — he does one or two public appearances before 9:30 in the morning, and three to four a night, “except for the last two weeks of December and the dog days of summer. And I don’t do half of the invitations I get here.”

And, as anyone who’s seen him in action knows, he loves every minute of it. “Yeah, I enjoy it,” says Ed. “And I think it’s an important part of being mayor. Everyone made fun of Wilson [Goode] for doing all those ribbon cuttings — and I was one of them. But I’ve learned that it’s very important that the mayor there makes e appearances, because they really buoy the spirit of the city. It’s the cheapest currency you have. The only price I pay is vis a vis Jesse [his 14-year-old son] and Midge [his wife, the newly appointed federal judge]. But they’re veterans.”

He also justifies it in dollars and cents. His stories of personally raising money for the city have been heralded not just locally but in the pages of the Wall Street Journal (Chief Cheerleader, Chief Beggar). He does almost nothing without a payoff.

“Hatfield Meats was willing to give the Rec Department $5,000,” explains Eddie, “if I’d declare it Hatfield Hot Dog Day and cook a hot dog outside City Hall.” Hell, he’d have declared it Hot Dog Month. “It took 30 minutes of my time to raise $5,000!” he boasts. It’s just one of the things he advises other mayors to do.

On the train ride up to New York the night before his meeting with Rudy, he was going through a stack of appearance requests for events back home in Philadelphia. One was for a sporting exhibit at the Franklin Institute — “Curt Schilling will be throwing out the first ball,” he says, writing YES to that one. Another was Wawa’s 30th anniversary celebration. He’ll also go to that. “Sure,” says Ed. “Wawa probably gives us $75,000 to $100,000 a year in contributions to different events. Again, it’s a tiny little investment of my currency to say thank you for all they’ve done for us.” How does he know how much Wawa gave? “Because I raised it,” says Eddie.

He estimates that since he’s been in office he has personally raised $50 million for various city causes — mostly for the Avenue of the Arts, which Ed tells the New Yorkers “will be much nicer than Lincoln Center,” and which he credits his wife Midge and Diane Dalto, the deputy city rep for arts and culture, for spearheading.

Local groups who book him to speak receive a letter that basically says: If you plan on buying the mayor a little thank you gift, please send a check instead to the library or the Rec Department. (“I don’t need 30 clocks,” says Rendell.)

“And guess what else I found out?” he says excitedly. “That I can marry people.” For $500, you too can be married by Ed Rendell. “I’ve done about six or seven so far,” he says. “I grouse when I see them on the schedule, but I like them when I get there. I’m an old softy. Sometimes I even get a little choked up doing it.

“But you have to pay $500, no matter who you are,” he explains. “And money goes to one of three things: The library, the Rec Department or the Avenue of the Arts. But Lis,” he says, “if you get married, I’ll up it to $5,000.”

I tell him not to let the city’s financial future depend on it.

And hopefully it also won’t depend on the fees he gets from his out-of-town appearances. Though many of the groups he speaks to pay him an honorarium — which goes into the coffers of one of those three favorite groups — when asked how much he’s raised on the road doing the Eddie Tour, he thinks for a moment then says, quite proudly, “I’d guess about $40,000,” which almost amounts to the annual salary of one cop.

“But,” adds Ed, “that includes the weddings.”

What Ed Rendell doesn’t brag about is the money he’s raised for Ed Rendell. Though the papers didn’t cover this, isn’t it a bit strange that three months before the gubernatorial primary, the biggest Democrats in town got together and raised more than $1 million for a mayor who won’t be up for reelection until 1995?

In February, just days apart, there were two $5,OOO-a-head fund-raisers. One of them, which he himself threw, drew over a hundred worshipers for cocktails at the Convention Center. The other one, dinner at Susanna Foo, hosted by big-time money-raiser Bill Batoff, had 25 Rendell fans nibbling dim sum. Batoff says Eddie needs to “replenish” his war chest for the ’95 mayoral race. “Let’s face it,” says Batoff, “he gave a lot of his money to [Russell] Nigro and [Bill] Stinson,” respectively referring, of course, to the failed Democratic state Supreme Court candidate and the recently dethroned and indicted Democratic state senator, accused of stealing an election from scrapper Bruce Marks in the biggest political scandal in recent Philadelphia history. (You can bet Rendell will also give some of his stash to whoever runs against Marks in the next round.)

Though Rendell handled the Stinson affair badly by anyone’s assessment — basically saying it was no big deal — he seems to have Tefloned his way out of that one. It was in the heat of the Stinson scandal that Philadelphians paid $5,000 each — more than most presidents have gotten here — to have a cocktail with him.

IN THE HOURS BEFORE he’s to meet with Giuliani, Ed’s booked as the guest speaker for the Carnegie Council Privatization Project — a think tank of gung-ho corporate types whom he will later refer to as “a little fanatical” and who have packed a room in an Upper East Side townhouse at 8:30 a.m. to hear his wisdom.

On the way over, Ed, who never prepares a speech, jots down a couple of notes in his tiny handwriting. “All right, what am I gonna say here?” he asks himself, chewing on his pen.

“You’re the mayor?” asks a woman at the registration desk, as Ed, in all his rawness, barrels in. He’s immediately introduced to Gloria, the woman running the event, whom he treats with grace and aplomb, and whom, he will later brag, he “totally charmed.”

“So he grew up in New York. Well, that’s interesting,” says a woman from the United Nations who’s sitting with a diplomat from Switzerland. “I met his predecessor,” she adds. “The black man with the entourage.”

Philadelphia is quite nice now, no?” adds the diplomat.

Rendell, who’s seated next to Gloria and some big shots from the new Giuliani administration, somehow refrains from scarfing down the plate of Danish they’ve laid in front of him. He has all of them laughing.

A stiff guy in horn-rims from Chase Manhattan Bank gets up to introduce him.

“I’m happy to introduce to you Edward G. Ren-dil,” he says — repeatedly. And then he launches into Ed’s bio, mentioning how he lost a race for governor, lost a race for mayor, then finally got elected to office with 68 percent of the vote.

Eddie gets up to the mike and says that he’s achieved such fame in Philadelphia that “it’s nice to come up here and have someone mispronounce my name…. And by the way, Brian,” he adds, “when I speak to groups in Philadelphia — especially if they want something — they go directly from my election victory as D.A. [in ’77] to my election victory as mayor and skip all the losses.”

They love him already.

And so he launches into his favorite How-I-Saved-Philadelphia anecdotes.

The union contract story.

The incentiveless workforce story.

The cleaning-up-City Hall story.

The tax-the-athletes story.

The parades-don’t-need-a-thousand-cops story.

Later he’ll even tell the fish-in-the-Delaware story. Oh, you didn’t hear that one? That’s when he took on the crazy environmentalists who wanted to waste city dollars on improving the oxygen level for fish in the Delaware River. “Are the fish dead?” he says he asked them. No, they said, but the water’s still below the EPA standard for what’s good for the fish. “How do you know? Did you interview the fish?” he says he said, as everyone roars. “I told them they could seek a court order and cite me for contempt,” because Ed Rendell would go to jail before he’d waste Philadelphia’s money on fish

His speech is peppered with as-I-told-Rudys. As in, “As I told Rudy, one area where you can’t miss: Collect taxes better.”

He also fires off his best sound bites: “There is no liberal answer to picking up the trash!” Yeah! “Short of taking an Uzi and gunning down your co-workers, you couldn’t lose your city job in Philadelphia!” Before he got there. Yeah!

Then he winds down, like he usually does. Just at the point where they’re nodding so vigorously their horn-rims are sliding down their noses, he hits them with self-deprecation: “And it was easy! That’s the funny part,” he says, while of them are actually taking notes. “This is not rocket science.”

The United Nations lady leans over and whispers, “He’s not very polished, but in his own simple way, he’s very effective, don’t you agree?”

Afterward, he agrees to take questions, and so many of the guests have one that he ends up spending an hour after the waiters leave indulging the line of people that formed in front of him. To some he hands out David Cohen’s direct line. To some, he instructs them to drop Cohen a short note. To some, he promises to put together a group of Philadelphians that they can come and visit, who will “help them in any way they can.”

“I grew up here,” he tells them. “My mom lives here. So any way I can help New York … “

“Excuse me,” says one Upper East Side type who’s been waiting for 20 minutes. “I didn’t pull either lever in November, because I didn’t like either candidate. And I was wondering-why don’t you come back and visit your mother on a full-time basis in about three years?”

Ed laughs. He also manages to point out that the New York Times got a letter to the editor that pretty much said the same thing. But, he says, “he’s your mayor.” And then he proceeds to do the best PR Rudy Giuliani can hope for. He the guy “you can’t judge a mayor by a campaign.” He explains that before his election, lots of Philadelphians thought he was just another pol “with bullshit campaign promises” too.

“Give Rudy a chance,” he continues. “He’s your mayor.” The jaded New Yorker is silent.

“It doesn’t matter what he did in the past.” And with this he segues right into: “I couldn’t care less what Bill Clinton did with the Arkansas state police. That’s history. He’s our president!”

Ed delivers this like he’s trying it out. And he seems to get exactly the response he’s after.

“I agree!” says the jaded New Yorker.

“So do I,” shouts a woman in line.

“I have one burning question,” says another woman in line, who promptly shifts the conversation from presidential affairs to municipal privatization.

When the line ends, Gloria, whom he’ll later refer to as “a helluvan attractive woman,” ushers him out. “Thank you so much,” she gushes. “You were so stimulating.”

MUCH OF THE SOURCE of Ed Rendell’s power began in the back seat of a car. It was January 1992 when Bill Clinton, then a nobody from Arkansas, came to visit Philly to drum up support, and Eddie took a ride with him from the Ritz-Carlton to Penn, where Clinton was giving a speech. Our mayor ended up throwing his substantial weight behind Clinton — one of the first prominent politicians to do so — mostly because they hit it off so well in the car, says Ed. He’s really fun to be around.” Eddie stood by Bill — even when nobody else did, especially when Clinton’s libido was first called into question.

A month after their backseat bonding, “when all the shit hit the fan about him [and Gennifer Flowers],” says Ed, loosening up on the train ride up to New York, “I was at a dinner for the Italian American Society, and I was sitting next to [Italian ambassador to Washington] Boris Biancheri — and we must have spent an hour and a half talking. And we got into the presidential election, and he said, ‘You know, mayor, no offense, but yours is a strange country.’ And I said, ‘How so?’ And he said, ‘All this talk of this Clinton and his love affairs. In our country it would only enhance his voter appeal.’“

The train passes Metro Park station.

“Have you met Biancheri?” asks Ed. “His wife is a great-looking woman.”

Anyway, Ed stuck by Bill, and Midge got tight with Hillary. “They get along terrific, just terrific,” says Ed. “And I like Hillary a lot. She’s smart, she has a great sense of humor, and I think she’s attractive. I know she gets beat up a little bit, but I think she’s attractive.

“When we were at the White House for the Philadelphia screening,” says Ed, “Bill took us on a tour of the Oval Office after the movie.” And, well, Clinton got a little goofy, says Ed. “And Hillary stood in the back and made good-natured fun of him, just as Midge would do.

“I probably shouldn’t say this,” he adds, “because it might not be taken right. I don’t want to sound conceited, but Clinton and I are very much alike.” How so? “We’re both gregarious and fun, we both love sports, we both have a genuine affection for politics and government and substance. We’re both married to successful women lawyers, we both have one kid the same age, we’re both lawyers and former prosecutors. We both have big hearts, we both love junk food and have problems with our weight. And,” he adds, laughing, “you can draw some other conclusions.”

The train slows down to a crawl and Ed is getting rammy. “This is most disappointing, “ he says. He looks at his watch. “What the fuck is taking so long with this train? We should be pulling into the station by now.”

Earlier, he fretted that he might not get to see his mother on this trip. Ed’s mother, Ruth, who lives on the Upper East Side, was stricken with Parkinson’s in 1977, the year her son was elected D.A., “and that put her in a chair for the rest of her life.” She’s 79 now and hasn’t been able to travel to Philadelphia since, so he often visits New York mainly to see his mother.

Rendell’s friends say his father’s death, when Eddie was 14, was the defining moment in his life. It’s why, when a cop is killed in Philadelphia, Rendell seems genuinely shattered. It is not good PR that puts him in hospital wards in the middle of the night, holding sleeping children while their mothers decide how to wake them to tell them that their father has been killed. Anyone who’s seen Rendell show up at the side of these families knows that every time a boy loses his father, he seems to relive it allover again.

Rendell grew up on the Upper West Side and in private schools. His mother’s family had some bucks — they owned Sloat Skirts, a large women’s sportswear company. And his mother worked for a while as a designer. His dad worked as a converter in the textile industry — essentially he was a middleman between the fabric mills and the clothes manufacturers. He died of a heart attack at 58/ But Ed, who’s 50 now, says it’s not fear or a cholesterol count of 240 that drives him to spend 35 minutes six days a week on the Stairmaster at the Sporting Club — where he manages to schmooze and sweat at the same time. “Every other male in my family, including my two grandfathers, lived into their 90s.” (Rendell has one sibling, an older brother who’s an international lawyer in Dallas; he says they are not close.)

“The bad news was I lost my father at 14. The good news is that I lived with him long enough for him to have a profound impact on me.” How so? “My love for sports, my love for politics, being a Democrat, caring about ordinary people my love for my son — because I’m sure it’s just a mirror image of how my father treated me. And he was a great believer in the golden rule.”

He pauses, then volunteers: “That’s why, when all this bullshit popped up during my campaigns, about me using my power position to abuse women…” He shakes his head over the rampant rumors about his libido. “That’s not true.”

What’s not true? “I’ve never done anything to hurt women — or men. And stop writing for a minute…”

When we go back on the record, I ask him about the topic he later brings up with the privatization fanatics: what he thought about Clinton and the state troopers. On the train, he rails back at me.

“It’s absolutely irrelevant and meaningless and, you know, there’s got to be a statute of limitations on this stuff! You gotta judge him on how he is as president. We’re gonna kill public life if we keep getting intrusive, intrusive, intrusive …

I tell him I agree.

“You do?”

I do.

We seem to relax. Enough to toss around another theory — that most great leaders have been philanderers. He seems to warm to this subject. “When you think of all the great leaders in history,” he says, “David Lloyd George, Konrad Adenauer — and just in America alone, FDR, JFK. … Even Dwight, everybody’s grandfather, was having a long-running affair with one of his attaches.”

We take this logic a step further. Not only were most of our great leaders philanderers, we decide, but the ones we really had a problem with weren’t.

“Look at Nixon,” says Eddie. And Carter, I offer. “Yeah. No question about it. It’s so silly. Elizabeth,” he says, looking out the window. “I think we’re passing through Elizabeth.”

A fellow passenger comes over to pay homage to Rendell. Ed responds in his usual charming way, then abruptly stands.

“Gotta hit the head,” he says. “Be right back.”

HOW DID WE COME TO love Eddie — Fast Eddie, who in his years as D.A. was best known for kicking in walls and throwing snowballs at Eagles games and hanging out at Apropos and being big-hearted. Eddie, who it is said used to sit in the dark at night in his office at Mesirov, Gelman, Jaffe, Cramer and Jamieson — thinking about what, Eddie, what? Eddie, who when his temper flares, is about as charming as the Missing Link?

The local answer is easy. Wilson Goode. After eight stultifying years with Congeniality — who, if nothing else, succeeded in diminishing our expectations — is it any wonder that we love Eddie? Or perhaps more accurately, that we want to love Eddie. We want him to save the city! We want to “love ourselves,” as he has actually put it. When did Philadelphians ever love themselves?

And don’t count Rizzo out of the equation. When we lost the Big Bambino, we were starving for a new local hero. But what’s amazing about Eddie is that while, Rizzo, he is beloved, unlike Rizzo, nobody seems to hate him. Or at least no is willing to admit it.

“I’m not Rizzo and I never can be,” says Eddie, “But I am more like Rizzo than I am like Bill [Green] or Wilson.” Does he think he’d be so popular if Wilson weren’t so unpopular? “I don’t think it’s Wilson so much. I think in Philadelphia, that certainly contributes to my popularity. But not nationally. Nationally, it’s just the dollars and cents, nuts and bolts recovery story.”

And so far those stories are so positively flattering that one wonders how long this honeymoon can possibly last. Is he worried? “A little bit,” says Ed. But I have tried, as you’ve seen, not to let this stuff make me think I’m anything special. In eight years — and I hope I’ll be there for eight years — I expect some downtime, some negative turns. Even now,” he says, with the public and press image so high, “there are constant defeats, constant defeats.”

Of course, part of the appeal of Rendell is, for lack of a better comparison, not so different from the appeal of the Phillies: He has managed to be both larger than life and Every guy. He can be smooth and he can be crude. He can be charming he can be boorish. He can be calculating and he can be reckless. He can be smart and he can be very, very dumb.

It is hard to imagine, for example, Rudy Giuliani bonding with Frank Guido from Staten Island. Or conducting the New York Philharmonic, for that matter. Or singing on a gay leader’s roof. But it is equally hard to imagine Mayor Giuliani sitting in a car with a female reporter and casually mentioning, as Ed Rendell did with me on a rather fascinating ride back home, in the presence of Frank the driver and prominent Philly lawyer Tom Leonard, one of Ed’s best friends, that he heard “something very interesting” about me. Then proceeding to tell me, in raw and alliterative terms, how he presumes I am in bed. All of which he says I “should find flattering.”

How does one respond to such a thing?

Does it really matter that a mayor who has clearly turned Philadelphia around can sometimes act more like an extra in Animal House than a public servant? Does it really matter that the national press, in the throes of its love affair with Ed, rarely sees the side of him that Philadelphia has come to accept? Does it really matter that America’s Mayor is probably more like America than anyone wants to admit?

But the really scary question is: Will Ed Rendell’s most notable attributes — that raw, unadulterated realness that makes everyone, this reporter included, a fan of his ability to govern — also be his undoing?

And who’s going to tell him where to draw the line?

It was cute, for example, at the train station — after I noticed he’d forgotten his bag in the car — when he gave me a little hug and said, “Lis, you’re a lifesaver I owe you one.” It was still pretty cute a few minutes later on the train platform: “Anything your heart desires. No task is too menial, too trivial or too abject.” Later in the train, it’s a little less cute as he’s going through his itinerary: “They didn’t schedule any time for me to do whatever you ask me to. Remember I owe you one.” Even the following morning, he’s still on this rant: He hopes to squeeze in a workout at the Plaza Hotel, he tells me. “Or,” he adds, “you can get your favor then.”

Does it really matter?

IN THE HOURS AFTER he meets with Rudy, America’s Mayor is off to the Plaza Hotel, where he is also staying (on Forbes’ dime), to be the star of a “Rebuilding America” panel summoned to discuss infrastructure in American cities. Unlike the other notables gathered for this conference, Ed Rendell is traveling sans entourage. Like he always does, much to the chagrin of his chief of security Anthony “Butch” Buchanico, who “feels responsible for him. Put in the article that he shouldn’t be traveling alone.” I tell Rendell I’m surprised he does.

“Why?” he asks. “It would be a total waste of money for me to take a policeman to New York and pay for him to stay in a hotel. I’m in no danger in New York.”

But surely all these fancy groups he speaks to would pay for the extra room.

“It’s not my style,” he responds. “Wilson would bring security into the Sporting Club. I could never do that. I don’t even let them come to Wanamaker’s, with me when I shop.

“I really don’t go for the monuments of power or any of that stuff,” he adds. “The Crown Victoria’s as good as I need. As you’ve probably noticed, I don’t dress very well, I don’t give a shit how many shoes I have.”

Between his privatization speech and his infrastructure speech, he is joined in the car by an old pal from the D.A.’s office — Rob Shepardson, a former Philly assistant D.A. now working in New York.

“The Ren-dil was deftly handled this morning,” Rob tells Ed.

“You think I should have ignored it?”

“No! It was great,” says Rob.

“So, how’s Jesse?”

Ed tells him about his son’s love of sports.

“Is he fast?” asks Rob.

“No, unfortunately that’s one thing he didn’t inherit from me. But when he was nine, he made an unassisted triple play. His mother was crying.”

Rob asks Ed if he’s seen The War Room, the campaign documentary starring political guru James Carville.

“No,” says Rendell. “Is it self-serving?”

“Sure,” says Rob. “Carville is absolutely magnetic.”

“James did an absolutely miserable job for Florio,” offers Ed.

“Can I interject?” asks Frank the driver.

“Sure, you can interject, Frank,” says Ed.

“Do you think Carville or the media won the election for Bill Clinton?”

Ed thinks about this seriously, then says if he had to pick one thing that put Clinton in office, it would be his ability — particularly in the debates and the town meetings — to connect with the people (something that is also Eddie’s forte.

Later, Rob asks Rendell who he thinks will win the Democratic primary for governor. And Ed says, “If Yeakel raises the money, she’ll win.”

“What about O’Donnell?” Rob asks, referring to former state representative Bob, the candidate Ed sort of endorsed back before O’Donnell lost his power as speaker of the House.

“I think it’ll be embarrassing,” says Rendell. “So how’s Jane?”

Jane is apparently a friend of theirs who has some acting ambitions. “I screwed up” says Eddie. “I got to be good friends with Demme from the start. I should have gotten her a speaking role.”

“How was the White House?” asks Rob.

Ed replies that the bed in the Lincoln bedroom was “woeful.” Too small and too old. And that being there didn’t have the “awe” he had expected, because Clinton “is so much like us,” he tells Rob. “Maybe if it were FDR or something.”

“So it was more like a sleepover?” asks Rob.

“Yeah,” says Eddie. “It was just like a sleep over.”

Now Frank wants to know what Eddie thought of the showboating of Rudy Giuliani’s son, Andrew, on Inauguration Day.

“That mother should have taken that kid by the scruff of the neck,” says Ed. “My wife,” he tells Frank, “would have taken our kid by the collar and put a stop to that, real fast.”

As we’re approaching the Plaza, Ed asks for one of Frank’s cards so that he can use him the next time he’s here “on personal matters.” By the end of the day, Rendell has promised Frank that he will “personally make a call to Rudy” and suggest that Giuliani hire him full-time.

Frank flips a card across the front seat. In the corner it says ARMED DRIVERS AVAILABLE.

“Armed drivers?!” says Rendell. “I love it. What a horrible city this is, Frank. Look at this traffic. There’s no excuse for this, Frank. It’s 11 o’fucking clock in the morning.”

Rendell’s infrastructure talk is scheduled to begin at 2:30. Mario Cuomo will be speaking at noon to the same “Rebuilding America” conference, but Rendell plans to blow off Cuomo’s speech, which he expects will be “a B.S. sort of thing,” and have lunch with Tom Leonard instead.

In the meantime, he retires to his room at the Plaza “to make some phone calls.” He says he wants to check in with the office.

Two hours later, when he emerges from the Plaza elevator, he’s late for his lunch with Leonard in the Prince Edward Room, but manages to squeeze it in before the infrastructure panel.

The first thing Rendell does when he shows up in the ballroom where the panel is to be held is re-arrange the namecards at the head table — so he can go last. Then he greets the other mayors in attendance, as if he were the star of the day, which, of course, he is. There’s Stephen Goldsmith from Indianapolis, who wears a Mickey Mouse watch and whom Ed refers to as one of the most innovative, progressive mayors in the country. Goldsmith also went to high school with David Letterman, whom Eddie loves, which leads to a ten-minute discussion on Letterman’s Andy Giuliani jokes — all of which Ed knows by heart. There’s Bob Lanier of Houston, a good ol’ Southern boy whose speeches, Rendell rolls his eyes through, but whom he slaps on the back like a long-lost friend. And there’s Meyera Oberndorf of Virginia Beach, a feisty little lady who loves Virginia Beach almost as much as Ed loves Philly, and who clearly amuses our mayor.

The panel ends up running late because the audience is still upstairs listening Cuomo. Rendell looks at his watch and laughs: “Mario must be waxing eloquent again.”

When the infrastructure panel finally begins — before a packed ballroom of New York lawyers, businessmen and other suits — Rendell manages, once again, to steal the show. But first, just as the mayor is stepping up to the seat he so carefully rearranged, Mayor Oberndorf mentions that Amtrak is virtually shut down and that Ed might have a hard time getting back to Philadelphia.

Rendell is genuinely surprised. “Why’s that?” he asks.

AND SO IT WAS THAT the mayor of our fine city spent 24 hours in New York without the foggiest clue that back home, the city was in a state of emergency. It was the day after the L.A. earthquake — which explained why Riordan didn’t show — and also the day the worst storm of the winter landed on Philadelphia, paralyzing the city for the next month.

But it isn’t until Ed is in the car at 5 p.m., with his pal Tom Leonard, that he learns what’s going on back home. Apparently, those two hours in the hotel suite didn’t include a phone call to David Cohen.

“What is happening in Philadelphia?” Rendell barks into the car phone to Butch, his chief of security. “Brownouts? Why are there brownouts? And why are the trains having problems?… I might have to send David to this thing tonight. They cancelled it? What’s going on?”

Frank offers to blow off his next two fares and drive Eddie back to Philadelphia. Eddie says okay — and he’ll even throw in some Flyers tickets — but only if Gloria from the Carnegie Institute, who hired Frank for the day for Rendell, will pick up the tab.

He hangs up on Butch and calls Gloria’s secretary.

“It’s Ed Rendell, from this morning,” he sweet-talks into the phone. “Listen, this is a great driver you got us …. Yes, I feel very safe with him. Yes, you should be commended. He’s a fine young man. And see, I have to get back to Philadelphia, but there’s a delay on Amtrak …. Yes, wonderful. Tell Gloria to call me if there’s a problem.”

Ed hangs up the phone and turns to Leonard.

“She’ll pay for it,” he says. “I charmed Gloria.”

A few minutes later, he punches in Cohen’s direct line. “David, I leave town for one day and you screw up so badly!” he says, laughing.

Cohen gives him the rundown: PECO is in such bad shape that they’re blacking out parts of the city for half-hour intervals. Firms have closed. The governor has declared a state of emergency.

“Oh my God,” says Ed.

In fact, says Cohen, the Packard Building, where Tom Leonard’s office is, really had it bad. The elevators were shut down and everything.

Rendell finds this terribly amusing, since the Packard Building is also where Bill Batoff works, and as he and Leonard chuckled earlier, “The Bates” was supposed to be hosting a big luncheon with U.S. Representative Dick Gephardt there today.

“So,” says Ed, “did Bates have to go home to Beverly [his wife]?”

They’re laughing raucously, he and Leonard. And Frank.

Then Leonard pipes in, suddenly serious. “Uh, David, what if it gets worse? .. Is there a priority list on the power? You know, to make sure kids get it first?” Cohen assures him everything’s under control. “David,” says Ed, “why don’t you go home, too? Save the energy.” He puts his hand over the phone and laughs.

Now Ed wants to talk to Butch again. He wants to know if “Hillary’s still coming tomorrow.”

He’s told that she’s not.

“Because of the weather?” asks Ed. “What the fuck is happening to this world? Earthquakes in L.A., brownouts in Philly …! can’t leave you guys alone for a minute.”

He hangs up the phone and thinks for a moment.

Then he calls his wife. He assures Midge he’s sticking to the low-fat diet she has him on, then hangs up and confides to Frank that “my wife is nearly perfect,” except that she’s a lousy cook. “She’s gonna be a judge,” he also tells Frank, “so all week she’s been interviewing law clerks. And they’re all 24 or 25. She’s gonna get herself a 24-year-old guy, Frank, I just know it.”

“Nah,” says Frank. “How could she do better than you?”

“True, Frank, true,” says Eddie, and for the next few miles, he’s staring silently out the windows — thinking of what, Eddie, what?

The following morning, the Philadelphia papers will report, in excruciating front-page detail, how the mayor’s office snapped into action to handle the state of emergency, without any mention that the mayor himself was out of town. In New York, the papers will have breathless front-page coverage on Rudy Giuliani’s plans to save the city, plans that are almost verbatim Rendell.

But for now Ed Rendell turns and asks Frank if he’d mind pulling into next rest stop.

America’s Mayor would like a hot dog.