Cradle to Grave

In the 1960s, a local couple became the most famous bereaved parents in America as their ten babies died mysteriously, one after another. In April 1998, a Philadelphia magazine investigation revealed the deaths were indeed tragic, but perhaps not unexplainable.

From the April 1998 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Homicide Hal has always been concerned that the Noe case is a ditzel.

The renowned forensic pathologist thought the case might be a ditzel back in 1963, when he did the autopsy on the sixth healthy infant that Art and Marie Noe had lost to “crib death.” And he was completely honest with that nun who called him at the medical examiner’s office in 1966 to inform him that the Noes were listing him as a reference on their adoption application — after having lost a record nine babies.

“I remember telling the nun there were two ways of looking at this,” recalls Dr. Halbert Fillinger, the 71-year-old Montgomery County medical examiner with the “Homicide Hal” license plate. “I said, ‘If you give Marie Noe a baby, she’ll either kill it quickly … or, if she had no hand in these deaths, nobody deserves a baby more than she does.’”

Everyone in the Philadelphia Office of the Medical Examiner (OME) had suspicions about the Noes back then, even though they never said so publicly. And, sitting in an office cluttered with antique murder-phernalia, Fillinger says he continues to have his suspicions today, 30 years after the tenth Noe baby died and the couple was investigated one last time and nothing came of it. While the Noes went on to rebuild their lives, their case lay dormant in OME file #30-68 and police homicide miscellaneous investigation file #11-1968. Just another ditzel.

“A ditzel is a case that looks like a goodie, but means nothing,” Fillinger tells me, his voice so gruff and breathy that everything he says sounds like it might become a dirty joke. “It’s a fairy tale you bought and you get it home and the last chapter is torn out. So there is no answer.

“Yes, I wonder what happened to those ten little kids. But there are so many blind alleys. You think you’ve got something meaty, but it’s like a papier-mache pizza. You keep thinking, Somebody must know something somewhere. But they don’t, because, well, it’s a ditzel.”

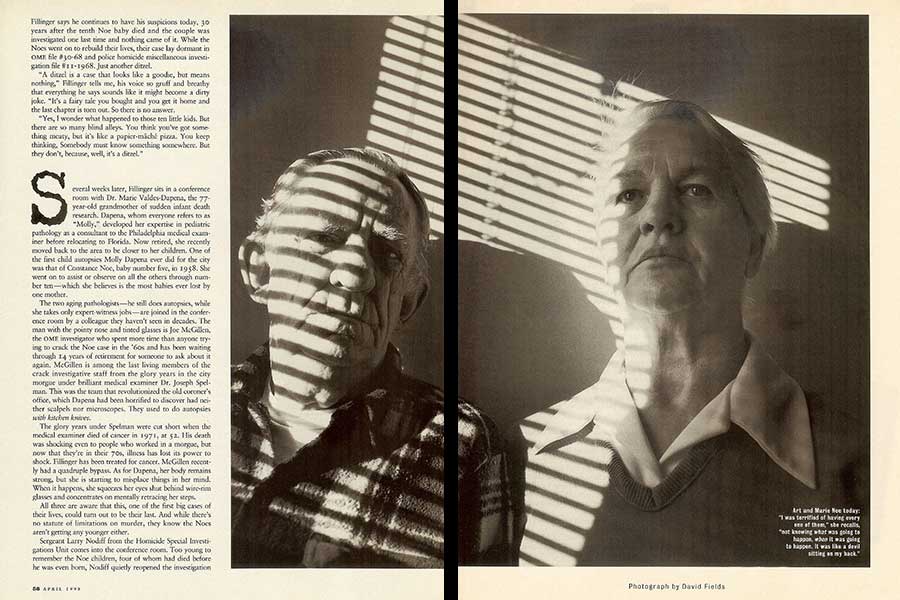

Several weeks later, Fillinger sits in a conference room with Dr. Marie Valdes-Dapena, the 77-year-old grandmother of sudden infant death research. Dapena, whom everyone refers to as “Molly,” developed her expertise in pediatric pathology as a consultant to the Philadelphia medical examiner before relocating to Florida. Now retired, she recently moved back to the area to be closer to her children. One of the first child autopsies Molly Dapena ever did for the city was that of Constance Noe, baby number five, in 1958. She went on to assist or observe on all the others through number ten — which she believes is the most babies ever lost by one mother.

The two aging pathologists — he still does autopsies, while she takes only expert-witness jobs — are joined in the conference room by a colleague they haven’t seen in decades. The man with the pointy nose and tinted glasses is Joe McGillen, the OME investigator who spent more time than anyone trying to crack the Noe case in the ‘60s and has been waiting through 14 years of retirement for someone to ask about it again. McGillen is among the last living members of the crack investigative staff from the glory years in the city morgue under brilliant medical examiner Dr. Joseph Spelman. This was the team that revolutionized the old coroner’s office, which Dapena had been horrified to discover had neither scalpels nor microscopes. They used to do autopsies with kitchen knives.

The glory years under Spelman were cut short when the medical examiner died of cancer in 1971, at 52. His death was shocking even to people who worked in a morgue, but now that they’re in their 70s, illness has lost its power to shock. Fillinger has been treated for cancer. McGillen recently had a quadruple bypass. As for Dapena, her body remains strong, but she is starting to misplace things in her mind. When it happens, she squeezes her eyes shut behind wire-rim glasses and concentrates on mentally retracing her steps.

All three are aware that this, one of the first big cases of their lives, could turn out to be their last. And while there’s no statute of limitations on murder, they know the Noes aren’t getting any younger either.

Sergeant Larry Nodiff from the Homicide Special Investigations Unit comes into the conference room. Too young to remember the Noe children, four of whom had died before he was even born, Nodiff quietly reopened the investigation into their deaths last October when I started asking him questions. In the months since then, I’d been tracking down the few people still living who had any firsthand knowledge of the Noe investigation, trying to reconstruct hundreds of pages of police, medical examiner and hospital records, many of which were believed lost. Fillinger, Dapena and McGillen are curious to reexamine the old files with the benefit of accumulated wisdom and offer the engaging homicide investigator their insights. But it is up to Nodiff to actually do something.

The Noe files are remarkably rich, with personal details going back over 50 years. The material is often excruciatingly personal, including many facts the Noes could not possibly know themselves. What their relatives, friends and neighbors really thought about them. What their doctors really thought about them. There are also autopsy reports on most of the children, but they raise more questions than they answer. The early ones carry definitive causes of death that any competent pediatric pathologist would now consider unlikely, if not impossible. Most of the later autopsies simply list the cause of death as “undetermined.” But as Dapena points out, “When an adult suffocates a baby by doing this” — putting her hand over her own mouth to demonstrate — “the autopsy shows nothing, zero.”

After several hours of plowing through documents, Dapena proclaims, “It just seems impossible that this woman is still walking around as free as a bird. … All cases like this are probabilities, but I’m 99 percent sure that these deaths were not a natural happening.”

Fillinger comes to his own conclusion. “This changes my whole concept of this case,” he says, pushing the papers aside. “This file really accuses them of murder. What this really says is that there’s no explanation for the multiplicity and the similarity in all of these deaths. The circumstances as laid out by the investigator’s interviews indicate a particular pattern that’s pathologically similar.

“I would have to go to the D.A. and say these people should be investigated.”

Maybe the Noe case isn’t a ditzel after all.

From the April 1998 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

There is something wrong with Marie Noe. When I visit her small rowhome in the working-class West Kensington neighborhood that used to be called Coopersville, it is one of the first subjects she brings up. She describes her problems in the past tense, yet when she cocks her head and purses her lips in a certain way, they seem acutely present. Marie is big-boned, but time has eroded her sturdiness. Now 69, she walks with an unsteady gait from a bad knee, and her doctor is concerned about lumps in her breast. She has mannish gray hair, fair skin, and wide eyes that are largely vacant, except when she is momentarily occupied with sadness or anger or some other emotion that defies easy description.

Art Noe, her husband of nearly 50 years, sits next to her in his black easy chair. Smaller than his wife, he is red-faced and bantam-feisty, the 99-pound weakling grown old, with a drinker’s eyes and a veiny nose. Almost fully recovered from a recent stroke, he has an urge to finish other people’s sentences, filling the achy silences with patter.

There is something wrong with Marie Noe. Whether it was caused by the trauma of her children’s deaths or actually caused her children’s deaths is hard to surmise. She may not know herself.

“I was very, I guess you would call it hard to teach,” she explains. “I came down with scarlet fever, and I was one of the ones they experimented on, with different drugs. I guess it took a toll on my … um, my noodle,” she says, with a chuckle, “and as I got older I got worse, trying to learn and stuff like that there — “

Art interrupts. “After we were married, I would make her sit down and read the dictionary, and take the mathematics tables off the old copy books. Now, she can do a checkbook, she reads books.”

“When we got married, I was practically illiterate,” she says. “My problem was never mentioned when I was growing up, but when I got married and seen how other people could talk, could read, could understand things better than I could, I understood I had a disadvantage.”

“She got me, and I taught her,” Art says. “That was it.”

“I would talk to a lot of doctors,” she continues, “and they told me it was just one of those things. It took me quite a while to understand…words, especially if it was a long word — “

“Like philoprogenitiveness?” Art interjects.

Like what?

Marie bursts out in weird laughter. Her husband knows a word that I don’t.

“I thought you were a writer,” he says. “Phil-o-pro-gen-i-tive-ness. It means ‘motherly love.’ The act of motherly love. Look it up in your dictionary.”

There’s a pregnant pause as he drags on the cigarette he’s not supposed to smoke, and then he prods: “Now I got a question for you. There’s only one word in the English language that has all the vowels. What is it?”

Marie laughs again. Something else he knows that I don’t.

“Sequoia!” he tells us triumphantly.

Art wonders why anyone would be interested in their story. While Life and Newsweek covered their misfortunes in the ‘60s, no reporter has been to their home to interview them since. I explain that my interest was piqued by some yellowed clips about their case, which is true, but only technically. The clips were listed in the bibliography of a groundbreaking new book on sudden infant death syndrome, The Death of Innocents, which contends that almost all serial crib-death cases should now be considered possible murders. The book focuses on the high-profile conviction of Waneta Hoyt, a Syracuse woman who admitted killing her five children, originally reported as SIDS deaths. It also examines how the Hoyt case inspired a 1972 paper that was the cornerstone of the widely accepted theories that SIDS can run in families and is caused by sleep apnea — sudden interruptions in breathing that can be prevented by hypervigilance and expensive monitors. Neither of these theories turned out to be true, nor did the estimate that SIDS was killing some 20,000 American children a year. Today, SIDS is believed to kill about 3,500 infants annually, down 36 percent since 1992, when doctors began recommending babies be put to bed on their backs.

In the book, Molly Dapena helps authors Jamie Talan and Richard Firstman drive the final stake into the genetic and sleep-apnea theories. She also speaks in passing about the Noe case, recalling that investigators had believed “it was likely a case of multiple murder.” But the book refers to the Noes by a pseudonym, and the case — mentioned only five times in 613 pages — gets lost.

When we first meet, the Noes are still unaware of their appearance in the book, but they know all about the reopening of the Hoyt case from seeing it on television. Art seems to understand some of the risks of being interviewed again, but ultimately believes, “You’re gonna write whatever you want anyway, right? Then you might as well meet us and hear it from us.”

While they can be as cranky as any elderly couple on a fixed income in a “changed” neighborhood, they are otherwise accommodating and surprisingly open. They mix up the names of the babies and the details of their short lives, but certain memories bring tears to Marie’s eyes. When that happens, she gets up and wanders back into the dining room, where the walls have been stripped for a repair Art will probably never finish, and then into the kitchen, where their three cats lounge on the floor, table and counter while their two dogs scratch on the back door to be let in. Art goes to comfort her, and they return momentarily to their easy chairs, which bookend a fireplace decorated with statues of Jesus, a large photo of Elvis Presley and snapshots of family members. On the wall is a print of Salvador Dali’s version of the crucifixion, as well as two faded professional portraits of Cathy, the Noe baby who lived the longest.

Marie does not get weepy when confronted with 30-year-old accusations about any role she might have played in her children’s deaths. “They really couldn’t prove I did any harm to the children,” she says, stone-faced. “Every one of them children didn’t have a bruise, didn’t have anything medically wrong.” Then she half-smiles, her indignation giving way to resignation. “Just one of them stupid things that happens. We just weren’t meant to have children, I guess.”

“The Lord needed angels,” Art sighs, “so we got a ton of them up there.” The first of our many interviews comes to a close, and Art sees me out the door, concerned where I parked. As I walk to my car, he asks if my wife and I have children. I tell him no.

“Don’t wait to have kids,” he calls out. “Don’t wait.”

Noe baby number one was Richard Allen, born March 7, 1949, at Temple University Hospital: seven pounds, 11 ounces, discharged five days after birth in good health, with slight jaundice, a rash, and abrasions on both knees from the delivery, all considered normal. The baby did not gain weight quickly, and the mother was so upset when he vomited that she brought him to St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, where he was briefly admitted for “colic.” Exactly one month after birth, the baby was discovered dead by the father, when he came home from working the night shift. Last seen alive by the mother, who was in the room, asleep in bed, when the baby was found either in a bassinet at the end of the bed (according to one report) or in a bureau drawer the couple used as a crib. Father ran with baby to neighbor, who drove them to Episcopal Hospital, where the infant was pronounced DOA. Cause of death attributed by coroner to “congestive heart failure due to subacute endocarditis,” a condition very rarely found in children. There was no autopsy.

Noe baby number two was Elizabeth Mary, born September 8, 1950, at Northeastern Hospital, seven pounds, ten ounces. Normal full-term birth, although the mother was hospitalized four separate times during the last trimester with false labor. No record of any major health problems until early 1951, when the five-month-old, 17-pound baby, who had a “slight cold,” was found by the mother “in her crib in the dining room … vomiting milk mixed with blood,” according to the police dispatcher report. Mother, who had just brought the baby downstairs and given her a bottle, phoned police and woke up husband, upstairs. Rescue squad brought baby to Temple Hospital. DOA. Cause of death attributed by coroner to bronchopneumonia. According to autopsy notes, this finding, which can only be confirmed microscopically, was made without any documented internal examination. Case was briefly investigated by police; inquest purportedly held, but no notes available.

Noe baby number three was Jacqueline, born April 23, 1952, at Episcopal Hospital, seven pounds, 2.5 ounces. No record of health problems until 21 days after birth, when she was found by mother vomiting and blue. Brought to Episcopal Hospital. DOA. Cause of death attributed by coroner to “inspiration [sic] of vomitus.” Autopsy reportedly performed, but notes are missing, and actual internal examination may not have been done. Inquest purportedly held, but no notes available.

Noe baby number four was Arthur Jr., born April 23, 1955, at Episcopal Hospital, seven pounds, 11.5 ounces. Only 12 days later, he was found by mother having difficulty breathing, brought to Episcopal, assessed to be healthy, and discharged. Next day, mother, home alone, again found baby not breathing and called the rescue squad. Brought to Episcopal Hospital. DOA. Cause of death attributed by coroner to bronchopneumonia after standard autopsy.

Noe baby number five was Constance, born February 24, 1958, in St. Luke’s Hospital, seven pounds, eight ounces. Born with conjunctivitis that cleared up quickly, the baby was discharged in good condition, although one treating physician later recalled a shocking interchange with the mother in the maternity ward. When informed that he would be helping with her baby’s care, mother reportedly said, “What’s the use? She’s going to die just like all the others.” On March 19th, mother called the family doctor to report that the baby was having trouble breathing. After making a house call, the doctor had the baby taken to the hospital because, although the problem seemed simply to be a cold that didn’t respond to medication, he wondered if something might be lacking in the infant’s blood. After three days of observation and testing, baby discharged in good condition. Two days later, father was at St. Hugh’s Catholic Church taking instruction so his marriage, an elopement, could be properly sanctified and his one-month-old daughter could be baptized. He returned home to find baby lifeless in her crib. Mother was upstairs, having just left child a few minutes before. When he pressed on baby’s abdomen to resuscitate, milk curds came out of nose and mouth. Rescue squad called, baby taken to Episcopal Hospital. DOA. Cause of death withheld 45 days for investigation by OME and police because parents had lost four other children.

Dr. Molly Dapena was asked to do the autopsy on Constance Noe. Even in the world of medical examiners, the brilliant 36-year-old pathologist was considered a curiosity. The former Molly Brown, a country girl from Pottsville, she had fallen in love after medical school with “a tall, dark, handsome Cuban man.” He was a pathologist, she became one as well, and even though they had a horde of kids — seven by 1958, on their way to 11 — Molly had decided to specialize in autopsies on children. She was one of just half a dozen such experts in the country. Dapena had recently asked medical examiner Joseph Spelman if she could do pediatric autopsies for the city. This was a relief, because no death affects a medical examiner as profoundly as a child’s, and nobody else in the office liked doing the tedious, finely detailed work on infant bodies.

Dapena quickly decided that the on-scene diagnosis of Constance Noe — “aspiration of vomitus” due to”natural or accidental” causes — was wrong. The vomit, she believed, wasn’t the cause of death at all but more likely the result of death, an artifact. The autopsy, however, didn’t reveal what had caused the death, so Dapena proceeded with extensive microscopic tissue examination and toxicology.

Both came back negative.

In the meantime, interviews were conducted by the police and investigators from the OME, who mostly asked about the parents’ health. They learned that Mr. Noe had a history of ulcers and was chronically underweight, weighing less than 100 pounds and classified 4-F by the military. Mrs. Noe was described as “slow in answering questions, constantly called upon husband to help her … and appeared either hypothyroid or under par mentally . . . [stated that] she was born in Phila. but does not know where or when and the recollection of most of childhood is clouded and vague.” With nothing more to go on, Dapena and the medical examiner had what records describe as “a long discussion” about what the official cause of death should be, and finally agreed it should be signed out as “Undetermined, Presumed Natural.”

Mrs. Noe was soon pregnant again, but her sixth baby, Letitia, was delivered stillborn at 39 weeks due to knotted cord, August 24, 1959, at St. Lukes Hospital. The body was turned over to the hospital’s anatomical board for medical study.

It was nearly three years before Mrs. Noe was heard from again. Baby number seven, Mary Lee, was born June 19, 1962, at St. Joseph’s Hospital, six pounds, eight ounces. The baby was delivered at 36 weeks by cesarean section, and Mrs. Noe experienced severe vascular collapse and anemia. Mary Lee was kept in the hospital for one month, although it is unclear if there was a respiratory problem — as her mother later recounted to police — or whether the new family physician, Dr. Columbus Gangemi, and the obstetrician, Dr. Salvatore Cucinotta, just wanted to observe. (The Noes were using St. Joseph’s in South Philadelphia instead of much closer St. Christopher’s, Episcopal and Temple because it was the preferred hospital of their new physicians.) Mary Lee was never again hospitalized, but Gangemi later told OME investigators that Mrs. Noe called him sometimes four or five times a day asking his advice and complaining that the baby “was getting on her nerves and that she couldn’t take all that crying constantly.” He described her to investigators as a “highly nervous and excitable individual but emotionally flat where the deaths of her children are concerned.”

On January 4, 1963, the couple was awakened by the sound of Mr. Noe’s elderly parents — who lived with them — fighting. Mrs. Noe took Mary Lee to her own mother’s house down the street and returned several hours later, but the infant was cranky and fussy and refused her bottle. Mrs. Noe later told authorities that she put Mary Lee down for “a short time” and when she returned, “the child was gasping for breath and turning blue.” She called police, and the rescue squad delivered the baby to Temple Hospital. DOA.

She then called Dr. Gangemi, who remembered her saying, without emotion, “Mary Lee is dead.”

Police took Mr. and Mrs. Noe to the 25th District precinct, where they were interrogated and released. In the meantime, an extensive autopsy was done by assistant M.E. Dr. Halbert Fillinger, the gregarious young forensic pathologist — half doc, half cop — who had done much of his training in Germany. Fillinger was suspicious about the death, but also worried about the immediate future: Mrs. Noe was three months pregnant. He was less concerned about her, a “bovine, docile, tranquil lady, not strikingly intellectually gifted,” than about the husband, whom he recalls seeing then as a “little bandy rooster of a guy who was feisty, troublesome and more than likely the instigator of any evil that went down.” But he and Molly Dapena both felt that someone should get involved in the situation. They arranged for a grant that would allow St. Christopher’s to offer the Noes free prenatal and postnatal care, delivery and hospitalization if they allowed their baby to be studied genetically and monitored.

The Noes refused on the advice of Gangemi, who told them that the high-profile physicians wouldn’t do anything he couldn’t and would likely take the child away and raise it. Fillinger recalls that Gangemi nixed the deal because they refused to name him lead investigator on the study. (Gangemi died in 1982.)

In April, the official cause of death for Mary Lee was announced as simply “undetermined,” rather than the previous “undetermined, presumed natural.” Then, in late June, Mrs. Noe went into premature labor, and at 38 weeks, six-pound Theresa was delivered by cesarean section at St. Joseph’s Hospital. The baby, whom the mother apparently never saw, died in the hospital after only six hours and 39 minutes.

While waiting for the autopsy findings on Theresa, Mrs. Noe became the most famous bereaved mother in America. A Life magazine story she and Art had been interviewed for just after Mary Lee died was finally published in the July 12, 1963, issue. They were referred to in the article by the pseudonyms Andrew and Martha Moore, but since the case had already received some local media attention, their identities became obvious to people in Philadelphia — among them a young assistant district attorney named Richard Sprague, later to become the most powerful lawyer in the city. According to police files, Sprague dashed off a memo to his staff asking why the first time the D.A.’s office ever heard about the Noes was in Life.

The article also drew attention to the rising prominence of Molly Dapena as an authority on crib death. But mostly, it set a tone of intense national sympathy for the Noes, especially Mrs. Noe, who was described as “worn almost to gauntness, and stung by sharp-eyed stares from her neighbors … her eyes are two enormous dark smudges in a face as gray as ashes. She seldom visits the children’s graves. Courage, in her lexicon, counts more than tears.”

Several weeks after the article appeared, the President and First Lady lost their two-day-old son, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, to respiratory problems, and the issue of infant death was high on the national agenda. The autopsy results on Theresa were then released. Cause of death was attributed by the medical examiner to a blood disorder, congenital hemorrhagic diathesis. While the problem hadn’t been found in any of the other children or during extensive tests performed on the parents, the autopsy finding dampened some of the investigative zeal for the Noe case. It was still “bizarre,” as Fillinger had told the Daily News, but now it was no longer five healthy babies in a row who died mysteriously after the mother was the last to see them alive. It was eight babies, and two out of the last three didn’t fit any pattern at all. “Theresa confounded me,” Fillinger recalls today.

In the meantime, the Noes had been busy taking care of Art’s increasingly senile and infirm parents, who’d lived with them for the past few years. Mr. Noe’s father had died the day before Theresa’s birth and death. His mother was hospitalized soon after, and went from the hospital to a private nursing home. After disputes between the Noes and the home over payment, she was moved to a public home, where she died in June 1964.

By that time, Mrs. Noe was pregnant again.

From the April 1998 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

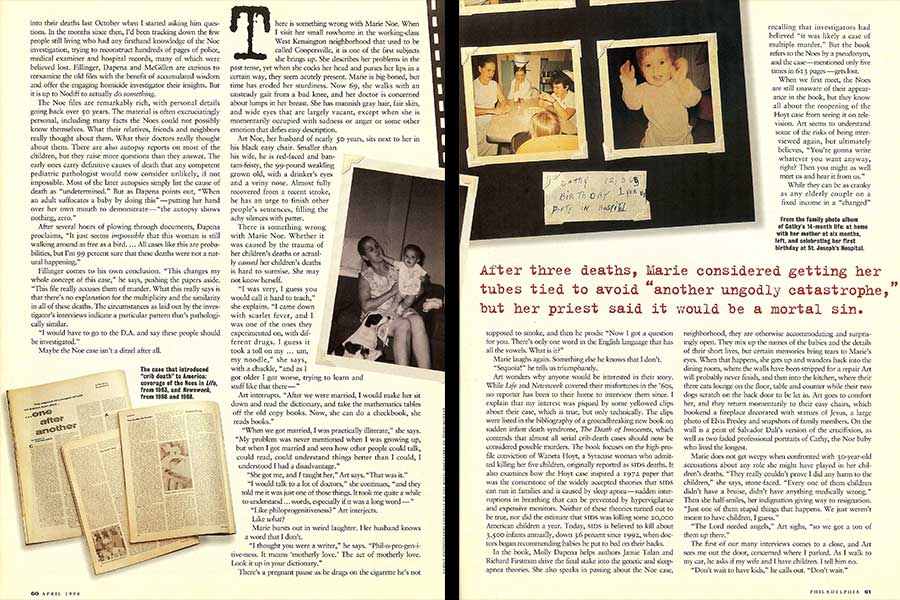

Catherine Ellen Noe, baby number nine, was born on December 3rd at St. Joseph’s Hospital by cesarean section; seven pounds, seven ounces. This time, the apprehensive doctors were taking no chances. Cathy was kept in the hospital for three months, even though she was perfectly healthy, and given every possible diagnostic test. Hospital staff kept a watchful eye on the Noes.

Many of the nurses in the pediatrics department were nuns in the order of the Sisters of St. Felix, and the supervisor of the department was a young Sister Victorine, who developed a close attachment to Cathy. She gave a statement to investigators at the time (and recently corroborated it in a telephone interview) in which she described Cathy as “a happy baby” with “no problems of any kind” during her entire hospital stay. She did, however, observe that when the parents came to visit, “Mr. Noe always was much more affectionate toward the child than was Mrs. Noe … [who] seemed to prefer to remain detached and aloof and dispassionate in her feelings.” The sister noticed, though, that when others were present, “Mrs. Noe would make a pretense of warming up to the baby, as if she felt it was required of her … [and] would utter inane little offerings that would have no bearing on the moment.” Victorine felt these remarks “were born most probably out of a peculiar need by Mrs. Noe to say something, anything at those times.”

Her nursing colleague, Sister Gemma, told investigators that not only did Mrs. Noe have an “apparent inability to establish a normal maternal rapport with her child,” but “there were times when [she] acted like two distinctly different persons.”

Victorine also noted that whenever the nurses allowed Mrs. Noe to feed the baby, she would always bring the food back to them claiming she couldn’t get her to eat much. Yet after Mrs. Noe would leave, the nurses would feed Cathy, who would consume all her food eagerly. On one occasion, Sister Victorine left Mrs. Noe alone with Cathy in the kitchen adjoining the ward. When Mrs. Noe couldn’t get the baby to eat, Sister Victorine overheard her say, “You better take this or I’ll kill you!”

Cathy was discharged in the early spring of 1965. In preparation, Dr. Gangemi hypnotized Mrs. Noe and gave her posthypnotic suggestions he hoped would instill confidence in her ability to raise the child and reduce her anxiety over the baby’s crying. He also gave her self-hypnosis/relaxation techniques to use every morning for a half hour — she still uses them to this day — and was pleased to see that they seemed to work for a while. That summer, the Noes enjoyed their pudgy-cheeked daughter, taking her to the World’s Fair in New York and to the shore. While none of their other kids had lived long enough to be photographed much, this time they even started a photo album. In it, Mrs. Noe often wrote down not only how many months old Cathy was, but how many days. “I was terrified having every one of them children,” she recalls today, “not knowing what was going to happen, when it was going to happen. It was like a devil sitting on my back.”

Mrs. Noe eventually again began calling Dr. Gangemi incessantly. And on August 31st — just after they had returned from the shore — she called claiming to have discovered Cathy in her crib, choking on a dry-cleaning bag. She said the baby had pulled the bag off one of Art’s suits that was hanging in a nearby closet. Gangemi later recalled being horrified and not even bothering to hide his suspicions, snapping at her, “Now, how could an eight-month-old baby get ahold of a large sheet of plastic off of a suit hanging in the closet?” Marie replied that she didn’t know, but “it was fortunate [I] found her in time.” Gangemi told her to take Cathy to the hospital immediately. When Mr. Noe was questioned about the incident later, he said the suit wasn’t hanging in a closet, but on a bar he had put between two side walls in the room for lack of storage space — which still didn’t explain why it was within the baby’s reach.

Cathy survived this bizarre accident but was kept in the hospital as a precaution for five weeks. During this hospitalization, it was again noted that Mrs. Noe had trouble feeding her daughter and that Mr. Noe was the more affectionate parent. Six weeks after Cathy was sent home, Mrs. Noe called the rescue squad, claiming that the child had “gone limp in her arms” while she was carrying her down the street. Cathy was revived with oxygen and taken to St. Joseph’s Hospital. She was kept there for three weeks, celebrating her birthday on the ward with her mother and several of the nuns. Photos from that day show what appears to be a perfectly normal and healthy toddler clapping with glee.

A week and a half after being discharged, and two days before Christmas, Cathy was brought back to the hospital after having what Mrs. Noe called “a spell.” By this time, the doctors and nurses treating Cathy had made some disturbing observations about these hospital visits. Dr. Gangemi later reported that the baby “would be crying terribly on admission and would act as if she was badly frightened. She would cry very hard whenever anyone came near her, and there seemed to be nothing physically wrong with her that would explain her distress.” The baby would calm down in about 48 hours, and it seemed to the doctor that “she gradually came to know she had nothing to fear from anyone there at the hospital.” She never had a “spell,” or any other new symptoms, while in the hospital. Gangemi later told investigators he hoped Cathy might survive until her fingernails grew long enough “so she would have a chance to defend herself.”

This time, Cathy’s hospital stay was over three weeks. At discharge, the Noes bought an inexpensive oxygen delivery system — regular oxygen tanks being prohibitively costly. Mr. Noe also put a screen door on Cathy’s bedroom so they could look in whenever they wanted, and he placed a walkie-talkie next to the crib, with the “talk” button taped down so they could hear her at all times.

The day Cathy returned home, the Noes celebrated a belated Christmas. Cathy got a baby doll with a toy stroller, a tricycle, a toy phone and a “Spell It” learning game. Ten days later, while Art was out having a beer, Marie found the baby having what she described as “a slight seizure,” and gave her oxygen. Two weeks after that, on Valentine’s Day, Marie said she had just finished doing the laundry when she checked on Cathy, who was napping on her stomach in the playpen, and found her turning blue. She said she tried to give the child oxygen, but her “tongue was between her teeth and her jaws set tight.” She called Gangemi, who made a house call. While he could find no reason for Cathy’s reported condition, he prescribed a liquid version of the antiseizure medicine Dilantin.

On the morning of February 25, 1966, Mrs. Noe was again doing laundry when she found Cathy unconscious in her playpen. She called the rescue squad, but when they didn’t respond quickly enough, she ran to her neighbor, who drove them to Episcopal Hospital. Cathy was DOA. Her bluish body was still warm.

At 2 p.m. that day, Joe McGillen and his partner, Remington “Rem” Bristow, arrived at the Noe home to discuss the ninth dead child. While McGillen was a hard-working OME investigator with glasses, prematurely gray hair and a flair for writing reports with dramatic detail, Bristow arrived with his own personal drama. He was the sharp-featured sleuth who wouldn’t rest until the city’s most famous unsolved murder, the “boy in the box case,” was cracked. Every year the media would cover him putting flowers on the grave of the unidentified child who had been discovered naked and dead in a cardboard crate.

The two OME investigators looked around the place and spoke to both parents, who had asked a lawyer neighbor to be present. While Bristow spoke with Mrs. Noe in the kitchen, McGillen quizzed Mr. Noe upstairs in the bedroom. According to their report to the medical examiner, Mr. Noe “admitted that it must naturally look suspicious … but he insists that he has never entertained the slightest doubts about his wife in this respect.”

Mr. Noe explained that his wife was more religious than he was, and while he had recently returned to the Catholic Church, neither of them was diligent in religious responsibilities. He also confided that he had had an alcohol problem and that his wife had helped him curtail his drinking. (Today, the Noes admit they both had drinking problems. Mrs. Noe says she often drank several glasses of wine in a day during her pregnancies because her doctor suggested it would help boost her low blood pressure. However, none of the babies displayed any symptoms associated with fetal alcohol syndrome.)

The next day, confidential sources told investigator Rem Bristow two interesting facts about the Noes. He learned that the bereaved parents were now hoping to adopt a baby. So he and his partner had to figure out how to quietly alert adoption authorities about the couple.

Bristow also learned that Mrs. Noe had once reported being raped, and he found a 1954 Inquirer police roundup story that included information about an attack on a Marie Noe. It said that a housewife had fainted after walking into her home, where she was surprised by a red-haired burglar who had been hiding in her bedroom closet. She said she awoke to find herself bound and gagged with her husband’s neckties — which is how her husband discovered her when he arrived home an hour later — and $15 missing from her handbag. According to her emergency room report, she told doctors that the stranger tied a necktie around her neck and then she fainted, yet her physical exam turned up no signs of physical trauma consistent with rape or strangulation.

Exactly nine months from the day of the attack, she gave birth to the son the couple named Arthur Jr. Bristow also found that Mrs. Noe had reported being raped in 1949, only weeks before giving birth to her first child. She told police that just before midnight a man sneaked into Art’s parents’ house, where the newlyweds were living, and attacked her while she dozed on the living room couch waiting for her husband to get home from the mill. Her father-in-law, sleeping upstairs, was not awakened, even after, as Mrs. Noe now recalls, she bit her assailant’s ear. There were no arrests.

One of Mrs. Noe’s siblings would later tell investigators about an even earlier sexual assault alleged by Marie, when she was a teenager. While the family was living in Cape May, Marie said she was raped by a man in the Coast Guard.

But even this was not the earliest trauma experienced by Mrs. Noe. McGillen and Bristow were able to piece together her tumultuous family history from interviews and a sheaf of old public documents generated every time Marie’s mother, a housewife and part-time cleaning lady, took Marie’s father, a wife-beating janitor with a drinking problem, to court.

Because of her parents’ troubled marriage, Marie ended up being committed to the Catholic Children’s Bureau. She was only in the orphanage for three months, but she celebrated her third birthday there before returning to live with her mother.

When she was five, Marie contracted scarlet fever, as did her younger brother. That same year, Marie’s 12-year-old sister was raped; a 40-year-old man was arrested and convicted for the attack. According to court documents, when Marie was 12, another of her older sisters gave birth to an illegitimate daughter, who was taken in and raised as Marie’s sister. Marie soon dropped out of school to work and help care for the infant. In fact, until she married, Marie was required to give every dollar she made to her mother, whom she recalls today as unloving, unsympathetic and sometimes violent, whipping Marie with a cat-o’-nine-tails. According to court documents, when Marie was 14, one of her siblings was sent to a state hospital for psychiatric treatment and was diagnosed with “post-traumatic personality disorder.”

A psychiatric profile of Marie Noe was emerging from the dozens of interviews the investigators conducted in the neighborhood (where the Noes lived in several different rented houses over the years) and from the decades of family hospital records they were subpoenaing. Family physician Gangemi told investigators he regarded Mrs. Noe as “an unstable schizophrenic personality who quite possibly is psychotic.” He also said that she “loves attention,” and when she was being treated for a while by a psychiatrist, “she seemed to make constant reference to this treatment as if all of this concentrated attention made her some sort of celebrity.” Investigators could not locate any records of this treatment, although Marie does recall attending several psychoanalytic sessions at Temple, during which she was given a Rorschach test but “didn’t see anything on those blots but a blot.” Her husband recalls joining her at one session, but he never returned because “it got too personal about lovemaking.” He also recalls having “a nervous breakdown” after the death of their first child.

McGillen and Bristow did, however, eventually locate a 1949 treatment record concerning an incident several neighbors and family members had told them about: the time Mrs. Noe went blind.

Only 12 days after her first baby died, 20-year-old Marie Noe was led into Episcopal Hospital by her husband. The doctor who examined her agreed she was completely blind — as she had been since 8:30 the previous evening, when she suddenly couldn’t see the television — and wondered in his notes if the condition was “conversion hysteria.” A psychiatric consultant confirmed the diagnosis, assuming the problem had been triggered by the baby’s death and the more recent news that a close uncle was very ill, but also commenting on her “inadequate personality development.” He recommended she be treated with an interview under the influence of sodium amytal, the so-called “truth serum.”

According to the doctor’s notes, Marie said under amytal that she and Art had decided that the baby’s death was unavoidable, and “she neither blamed others nor herself.” She said she very much wanted another baby, and in fact, the day she became blind, Art had told her that he “would not permit her to have another child.”

She said that since the baby died she felt like a stranger with her husband, and if financially able, she would leave him. She said their married life had been adequate before the baby was born, but now intercourse was prohibited.

The doctor believed that Marie Noe “verges on inadequacy but will probably be able to adjust if [her] husband will grant her wish to have another child.” The interview itself, however, was enough to restore her sight, and she was discharged the next day.

What she apparently did not reveal to doctors was that she had been experiencing temporary blindness for years. Today, she recalls briefly going blind before she got her period almost every month, ever since her first menstrual cycle at 14. She associated this blindness with headaches, which she also got premenstrually. Severe migraines can cause physiological blindness that responds to medication, but Marie Noe’s responded to a psychiatric intervention. She doesn’t recall having the headaches and blindness as much after undergoing “truth serum.” On the other hand, she spent almost half of the next 18 years either pregnant or recovering from childbirth.

“I would get these enormous headaches,” she explains today, “and the doctor told me I was getting migraines from the loss of a child, and maybe it might help if I got pregnant again. So I got pregnant again. I was like a factory. I was easy to get pregnant.”

While the investigation continued, the Noes held a viewing for Cathy, which many of the nurses from St. Joseph’s attended. Sister Victorine, who has since left the order, still has the mass card. Then Cathy’s autopsy results came back. The cause of death was “undetermined” — again, no mention of it being “presumed natural.”

There was a renewed media frenzy over the case that the Noes in no way discouraged. They gave interviews to the major local newspapers, as well as to Newsweek, which did not disguise their names as Life had. The Newsweek article was mostly about the phenomenon of crib death — a subject the Philadelphia medical examiner’s office was developing a national reputation for researching — and primarily used the Noe case as a way to examine the troubling subject. The M.E.’s party line on the case was that there was “absolutely no suspicion of homicide,” a statement he apparently did not believe. Cathy had died at 14 months, and his own research, as noted in the article, showed the average age for “crib deaths” was “between two and four months of age and seldom before three weeks and after six months.” In fact, not one of the Noe children had died between two and four months.

In the meantime, Joe McGillen was busy investigating a new angle: The Noes’ finances, and insurance policies taken out on the babies. Mr. Noe said he grossed just over $200 a week as a machinist, and besides his $50-a-month rent, which was a month overdue, he owed over $4,000 to a finance company, a church credit union, several stores and St. Joseph’s Hospital. The investigators noted that the otherwise modest house had a new refrigerator, washer, dryer and television set.

Before working for the medical examiner, McGillen had toiled at a company that investigated life insurance claims. While he knew it wasn’t unusual for parents to insure infants in those days, he looked into the policies taken out by the Noes. Of the seven Noe children who had actually come home from the hospital, there was evidence at least six had been insured — the first few for only $100, but from baby number four on, for over $1,000.

The company that paid out claims on Arthur Jr., Constance and Mary Lee had rejected the Noes’ application for a $1,000 policy on Cathy the previous March. But Mr. Noe, who worked on the side as a ward committeeman in North Philadelphia, was apparently able to use political connections to find another company to write a $1,500 policy. The application was taken in September, while Cathy was still in the hospital after the dry-cleaning-bag incident. The policy was issued on November 25th, just days after Cathy had again been admitted to the hospital.

Cathy died exactly three months after the policy was issued, and the company promptly refused to pay the claim. The application form failed to mention anything about the Noes’ other children. There was also the matter of the salesman having claimed to see Cathy in the house when he took the application, even though records showed she was in the hospital the day he visited the Noe home. Since it was unclear if the Noes or the salesman had fudged the application, a lawyer helped them get a settlement of $500.

Could one of the parents be killing these kids for the insurance money — as modest as it seemed, barely enough to cover the funerals? It had to be considered a possible motive, especially after McGillen had a troubling phone conversation with Sister Michael Marie, the nun who had offered to keep him apprised of the Noes’ adoption application. In the deluge of mail they’d received, the Noes had actually been offered several children by pregnant women who had read about them, but they preferred to use the local Catholic Children’s Bureau. Sister Marie reported that the Noes had attended one of the group meetings the Bureau held for prospective parents. When asked afterward how he felt about the meeting, Mr. Noe reportedly expressed surprise that no one had asked “whether one was permitted to insure an adopted child.” Sister Marie told the investigator this was most unusual; in fact, she couldn’t remember anyone else ever bringing the subject up.

Even though the Noes had been told when they made their application that it would take at least nine months to get a child, they couldn’t understand why the church was taking so long. When a Bulletin reporter was sent to their house for a human-interest story on a slow news day — only five months after Cathy’s death — they complained to him that the agency was “dragging its feet.” But before nine months were up, the adoption wait was over. McGillen learned that the Noes had withdrawn their application.

Mrs. Noe was pregnant. She had come in, Sister Marie recalled, “very exuberant as she announced the news to the nuns,” who noticed “that her whole manner and outward appearance was different.” McGillen called the Noes’ physician, Dr. Gangemi, to confirm the news.

“Yes, unfortunately, I’m afraid that’s true,” he said. In fact, Gangemi wanted to know if there was anything the M.E. could do to relieve him of the responsibility of caring for Mrs. Noe. When informed of the pregnancy, the medical examiner himself contacted the Department of Health’s special Maternal & Infant Care Project to see if they might be able to intervene.

But all anyone could do was watch, wait and worry.

Arthur Joseph Noe was born on July 28, 1967, at 9:57 p.m., in St. Joseph’s Hospital, eight pounds, five ounces. The delivery was by cesarean section, complicated by the rupture of Marie Noe’s uterine wall. Before delivery she had been told by the obstetric surgeon, Dr. Cucinotta, that there was a strong possibility she would have such a problem while under anesthesia and he might have to perform an emergency hysterectomy. She gave him her consent, and in fact he did need to remove her uterus in order to save her life.

Cucinotta, who at 86 still remembers the Noes and the procedure vividly, is adamant that the hysterectomy was medically necessary and was not done just to stop Mrs. Noe from having more children. However, he had been suspicious of the Noes for several years and had implored Mrs. Noe not to get pregnant again after the death of Cathy. And he recalls asking his lawyer about his legal responsibility to report his concerns to authorities. Instead he discussed his concerns only with Gangemi, who referred the Noes and many other patients to his practice. Cucinotta was never made aware of any investigation.

Cucinotta handed newborn Arthur Noe to Dr. Patrick Pasquariello, today a senior pediatrician at Children’s Hospital, who recalls carrying the baby from the delivery room to the nursery. He, too, was very suspicious of the Noes, but says it was a time when “people weren’t as tuned in to what to do with those suspicions. Today, the kid gets a bruise and you file a form. Back then, we were only starting to hear about SIDS and child abuse and all that.” Yet he knows the staff was anxiously watching baby Arthur — the second baby Arthur — whom the Noes called “Little Arty.”

During the two months that Little Arty was kept in the hospital, the staff had plenty of time to observe him. As Gangemi noted emphatically on his chart, “The child appears normal in every respect. NEVER has this child displayed any … respiratory embarrassment [as] described by the mother [in] her other now-deceased infants.”

The attentive hospital staff did not get much of an opportunity to observe the Noes, however. According to a medical examiner’s review of the baby’s chart, during the entire two months that Little Arty was in the hospital, the mother and father visited him two times.

Arthur Noe was discharged from the hospital on September 29, 1967. At the end of his discharge note, Gangemi wrote: “In God We Trust!”

One month later, Gangemi got a call from St. Christopher’s Hospital that baby Arthur Noe had been brought in by the rescue squad. Mrs. Noe, who had been home alone with the baby, said that while she was feeding Little Arty, “something must have gone down the wrong way,” and he began choking and turning blue. She said she “banged it out of his chest,” called the rescue squad and gave him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. By the time the baby arrived at the hospital, he was “pale but not cyanotic [blue] … flaccid but in no apparent respiratory distress.” Gangemi asked that the baby be brought down to St. Joseph’s Hospital, where he remained for 19 days.

Except for a stuffy nose and two normal regurgitations after feeding, the baby was fine. Chest and head X-rays were all normal. The only thing abnormal noted on the chart was the number of times the parents visited their only child. It said the mother showed up once in 19 days — when the administrator asked her to come in to discuss a bill — and the father didn’t visit at all.

Five weeks after discharge, the baby was rushed to the emergency room at St. Christopher’s, this time by police. According to the chart, Mrs. Noe explained that “the family cat laid across the baby’s face this morning and when [she] found it, the baby was crying and blue.” Little Arty was promptly revived with oxygen. The E.R. doctor’s assessment was that this was a “possible attempted suffocation.” Still, the baby was sent home, to be seen by Gangemi in the afternoon.

Christmas came four days later. Little Arty’s stocking was hung on the living room wall under a carved wooden cross a family friend had made to memorialize Cathy. The baby was showered with stuffed animals — two big teddy bears, a giraffe and a cow.

When he was later brought to the Roundhouse for questioning, Mr. Noe told police it was the best Christmas he ever had.

Eight days later, just after 4 p.m., the rescue squad took Little Arty to the St. Christopher’s emergency room, DOA. He had been found by his mother. Within hours, police and medical examiner investigators were at the Noe home, reading the couple their rights. This time they did not have an attorney present. Mrs. Noe said she did not feel she needed one.

“I have nothing to hide,” she said, “… [and] I will tell you everything I can possibly remember.”

She told investigators about the baby’s earlier hospitalizations and the incident with the cat, which she described this time as, “The cat was trying to get something from the playpen and scratched the baby on the head.” (There is no mention of a scratch in the E.R. report.)

She went on to explain that the baby had had a cold the week before and had been taken to Gangemi with a fever. The day before Little Arty died, he was, as she recalled, “quite cranky” as a result of teething, and her husband got some Orajel, which seemed to help. The next day was uneventful until just after 2:30 p.m. The baby was upstairs napping, and Mrs. Noe was down in the kitchen starting the chicken for dinner.

That’s when she said she heard the “crib rattling.”

According to her statement to police, the baby “didn’t cry out.” Yet she decided to take his shoes up to him. When she entered the room, the baby was “face up, gasping for breath and turning blue,” she recalled. “I immediately lowered the side of the crib and started mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. This did not appear to be doing any good and I … called the rescue squad … and came downstairs with the baby. … I placed him on the kitchen table and started mouth-to-mouth resuscitation again and tried to help it. … I called my husband and he started home. The rescue arrived but the child was DOA.”

When questioned, Mr. Noe had little to add, except to say, “I have no idea why this is always happening to us. I wish to God I did.”

In the weeks following Little Arty’s death, McGillen did nothing but investigate the Noes. He was joined by his partner Bristow and veteran police homicide detective Joseph Schimpf. Besides interviewing family members and caregivers, McGillen also chased down leads from a woman who had anonymously called the medical examiner three days after Little Arty died. She claimed to have known the Noes very well for 27 years and was now convinced that “Marie was doing something to the children.”

According to McGillen’s notes, the woman I’ll call Doris talked about the old days, when Marie and Art met at a small private club in the neighborhood. She recalled Art being overwhelmed by Marie, who had a reputation in the neighborhood “of being boy-crazy.” Their whirlwind courtship was often criticized, she said, by Art’s mother, who never liked Marie; she was very outspoken in her criticism of Marie as a housewife and was “always complaining to neighbors that Marie never cared properly for the children.”

Doris also said it was a very close-knit neighborhood, and that she and her husband were exceptionally close with the Noes. She had vivid recollections of helping Marie care for the first three children, all of whom appeared healthy. She did note, however, that Art often complained his wife seemed to care about nothing but having sex, and that he “was growing weary trying to satisfy her.” She told the investigator it was no secret in the neighborhood that Art would confront Marie angrily about her flirtations with other men. She also recalled Marie claiming to be the recipient of obscene phone calls and describing them in graphic detail. She said neighbors saw this as Marie’s attempt to “call attention to herself,” which is also how they perceived her alleged rape in 1949.

Doris said that in the time she knew the Noes, numerous house pets-dogs, cats, fish, turtles, parakeets-died mysteriously, and that Marie once complained to her, “Everything I touch dies!” She especially recalled a cocker spaniel she gave Marie for company after the death of one of her babies. According to Doris, one day Art came home from work and the dog was gone. When he asked her about it, Marie replied, “I called the SPCA and had it put to death because it had the raves.”

When the first two Noe babies died, Doris was willing to believe that the deaths were natural, especially since the coroner’s reports validated that view. But after the third child, Jacqueline, died in 1952, she said, everyone in the neighborhood became suspicious of Marie. The suspicion only increased when Marie disappeared one afternoon and Art couldn’t locate her until the next day, when she called from Florida and asked him to come get her. It was the first of several brief disappearances that neighbors recalled.

Doris remembered a 1954 christening party for a neighborhood child at which people were so wary of Marie they “agreed beforehand … no one would leave the baby unattended.” As the party progressed, everyone had a few drinks, and the baby was briefly forgotten: “Suddenly … someone called out, ‘The baby!’ and with that everyone hurried upstairs … to find Marie Noe bending over the baby’s bassinet with her hands up near the baby’s throat. Someone yelled her name and she straightened up fast … [exclaiming] she had only been straightening the baby’s covers.”

While many of the incidents in Doris’ statement were later confirmed by the Noes, few of the friends and family members she suggested OME investigators interview would admit to being quite as suspicious of Marie. Most said they didn’t really know the Noes well — including family members who hadn’t communicated with them for years — but that their children appeared to be well cared for. Many recalled seeing Marie out and about each day pushing the baby carriage, although several recounted a similar description of her as “a strange person … one time she will see you and say hello, and another time she will pass you by as if she never knew you were there.” Most felt badly for the Noes and couldn’t imagine them harming their children.

The Noes knew they were being intensely investigated, even followed in their neighborhood. “I see this guy sitting at the bar,” Mr. Noe recalls today. “I said to Marie, ‘That’s the detective from the 25th precinct.’ So I said to the bartender, ‘Jack, do you have a Polaroid camera?’ He did, and I said, ‘Whatever he’s drinking, give him a drink on me and snap the camera at him and say, “That’s from Mr. and Mrs. Noe.”‘ He got off that stool and I never seen him again.”

In the meantime, the medical examiner was telling the press that there was nothing suspicious about the ten dead babies of Mr. and Mrs. Noe. “Spelman says he found absolutely no evidence indicating an unnatural death,” Newsweek reported on January 15, 1968, in what would become, for 30 years, the last published word on the case.

The Noes were led to believe that any suspicions about them disappeared when they passed the polygraphs. “We had the lie detector test, they let us go home, and that’s all we ever heard from them,” Mr. Noe recalls.

Neither the Noes nor the public ever learned medical examiner Joseph Spelman’s true feelings about the case. But buried in the autopsy files of Arthur Noe are two identical letters that make the opinions of the late pathologist crystal-clear. One is addressed to the city office overseeing adoptions, foster home placements and child protection services, the other to the corresponding state agency. Both were written in response to comments Mrs. Noe made to investigators McGillen and Bristow at the funeral home during Little Arty’s viewing. When asked how she intended to occupy her time, Mrs. Noe said she would still like to adopt a baby or take in a foster child.

Spelman’s letters read:

“You undoubtedly have read about the death of the tenth child in [the Noe] family. … This office has actively investigated several of these deaths. We have extensive files on the background of this family. We are not willing to declare with certainty that these children died natural deaths.

“In the event that thought is given to placing children under the care of the Noes, we would be glad to discuss our file and our thoughts in detail.”

Yet when Spelman had the opportunity to list a cause of death that was more likely to provoke continued investigation, he didn’t. If the cause of death had read, for example, “undetermined, consistent with suffocation,” both the media and the police might have been encouraged to pursue the case further. But by that time, Spelman may not have had enough political clout left to take such a bold public stance against a publicly sympathetic mother. Fillinger points out that the medical examiner had successfully battled a well-known drinking problem, and that his chief pathologist, the outspoken Dr. Joseph Campbell, had barely survived an attempt to fire him over his erroneous testimony in a case. In the months after the last baby died, Spelman may also have been distracted: He was designing the new morgue (still in use today), he was called to testify in the autopsy of Mary Jo Kopechne, who had drowned in Senator Ted Kennedy’s car, and then Campbell, his second-in-command, was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Campbell died in 1969, at the age of 44. Spelman died two years later.

During his lifetime, Spelman’s true feelings on the Noe case were voiced only once — not by him, but by Molly Dapena, in front of two dozen infant mortality experts who had gathered on a remote island in Puget Sound to decide the future of research on sudden infant death. (It was at this 1969 conference that “crib death” was officially renamed SIDS.) After a presentation, a doctor asked about the public perception that SIDS “runs in families,” a misperception popularized by coverage of that “family in Philadelphia” in the lay press.

“I’m familiar with that particular family,” Dapena announced. “Dr. Joseph Spelman, the chief medical examiner of the city of Philadelphia, has concluded that these children did not die of SIDS. However, because of legal implications, we are not at liberty to report the results of his investigation.”

There is no record of the case ever being discussed publicly again until 1997, when the Noes were mentioned by pseudonym in The Death of Innocents.

Retired homicide detective Joseph Schimpf, now 77 and slowly recovering from two open-heart surgeries in a small town in Tennessee, doesn’t see why the Noe case should be brought up again. He stands by his 1968 conclusions. “It’s still the same old case,” he says, gasping for breath between phrases. “The guy in the coroner’s office [McGillen] still thinks the lady is responsible, and I still don’t. I didn’t see no kind of evidence. [Mrs. Noe] was supposed to be kind of slow, not ‘with it,’ so I don’t see how she could have fooled all these more intelligent people. …I don’t think she was bright enough to kill everybody and nobody knew how she did it. … There was a possibility they were involved in two or three of the cases. …I guess I’m just of the opinion that there’s something screwy but she’s not guilty.”

Molly Dapena feels differently. “It is truly incredible to me that nothing was done,” she says. “And one wonders why, since Dr. Spelman thought it was murder back then.”

Yet when some of Dapena’s colleagues are told that one of the main reasons the Noe case is being reinvestigated is because she boldly spoke out — first to the authors of The Death of Innocents and later to me — they are flabbergasted. They recall Molly Dapena in the ‘60s and ‘70s as a prominent voice shouting down the idea that a mother could kill her children.

Besides her teaching and autopsy work, Dapena was, in those days, the great debunker of theories about crib death. Using the files of the Philadelphia OME as a database, she wrote authoritative papers in top journals disproving that SIDS was linked to viruses, to parathyroid abnormalities, to changes in the conduction system of the heart or to retention of something called “brown fat.” But as a mother of 11 children herself and a stickler for a purely scientific interpretation of autopsy rules — at a time when public health officials were beginning to improvise in order to address the growing problem of child abuse — she developed a reputation for having a maternal blind spot. Dr. Dimitri Contostavlos, a former Philadelphia assistant M.E. who is now the Delaware County medical examiner, says,”She and her gang had a sort of ‘no-mother-can-do-any-harm’ philosophy.” He remembers her as being too focused on the strictest possible interpretation of the physical autopsy results and not willing enough to consider the circumstances surrounding a child’s death. He remains annoyed that when the city prosecuted a mother in 1971 who admitted smothering three children whose deaths were previously attributed to SIDS, Dapena testified for the defense about the righteousness of the “undetermined” causes of death.

Fillinger also recalls, “Molly testified a lot for the defense in child-abuse cases, and felt inclined as a mother to see the mother’s side of it. We were more prosecutorially oriented. But she was such a sweet girl, and she knew so much that you readily forgave her any tenderness of heart that might make her see the side of a parent in a sympathetic light.”

After being told what her colleagues said, Dapena thinks for a moment. “Well, I don’t remember being terribly upset at the time that [Mrs. Noe] was a mother who was murdering her children,” she says, literal-minded as always. “But I think that’s because I was an innocent in this regard. The person who became suspicious was Spelman. He was more wise about this. I was an innocent.”

She was also an innocent about the theory that SIDS was caused by sleep apnea and could be prevented by monitors, which she “bought hook, line and sinker” at the time. It became a theory SIDS mothers embraced, using it against researchers who suggested that a small percentage of the deaths might be infanticides and who sought to explore the psychodynamics of child murder. New York psychiatrist Stuart Asch was among the first to try to get pathologists interested in the subject. While studying crib death for the New York City medical examiner in the ‘60s, Asch developed a theory that individual child murders are often committed by mothers suffering from severe postpartum depression — almost a form of suicidality that can be treated and rarely occurs — but that serial cases are something else entirely. “These mothers are infantile, self-involved, narcissistic and probably simple schizophrenics,” he declares. “To them, the baby is not seen as a person. These women seem almost autistic in that way, because they have no feeling for the baby, don’t understand what the baby is doing. The reason for killing the baby is probably [that] she wants a relationship, she wants people to pity her.” Asch recalls lecturing about his theories at a psychiatric conference in the early ‘70s and getting an earful from audience member Molly Dapena, who “said she doesn’t believe crib deaths are murder.”

In 1977, a new diagnosis called Munchausen syndrome by proxy appeared in the literature. In the most common manifestation of this bizarre pathology, a mother either fakes or deliberately causes a child’s recurring illness in order to create increasingly intertwined relationships with doctors and nurses. Munchausen mothers typically suffocate or poison their babies. While Munchausen by proxy would become a catch-all diagnosis for serial SIDS cases, Dr. Stephen Ludwig, longtime child abuse expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, believes the Noe case could be even more complex. The Munchausen mothers he has known showed no other signs of mental illness, were extremely intelligent, and were always attentive to their children in the hospital. It was also clear what they hoped to gain from their behavior: multiple hospitalizations that brought attention from doctors, not necessarily the deaths of their children. Ludwig wonders what else the Noes might have had to gain from the deaths, noting that he has seen Munchausen families who got the attention they craved from the press. Ludwig also wonders if these acts could have been carried out in a dissociative state, a separate consciousness, so Mrs. Noe wasn’t really cognizant of what she was doing and later couldn’t remember what she had done. A noted psychiatrist suggests that the first Noe child might have died from natural causes, and the subsequent near-misses and deaths could have been caused by Mrs. Noe reenacting the loss in a dissociative state.

Ludwig recalls that in the early ‘70s, city agencies and hospitals weren’t prepared to deal with “even straightforward cases of child abuse,” so he’s not surprised a case as tangled as this one was dropped. But he believes this level of mental illness could still be diagnosed today by a good forensic psychiatrist. “A thorough investigation is not only warranted, but these children demand it,” he says.

But by the time these kinds of ideas were coming to the forefront, Molly Dapena had left Philadelphia and the OME. Her husband insisted on moving the family to Florida, so Dapena and the five children they still had living at home joined him there, and she took a position at the University of Miami Medical School. Her husband soon left her to marry another woman, and then suffered a stroke during his honeymoon in Paris, rendering him a near-invalid. Dapena not only supported her children, she also helped her ex-husband’s new wife take care of him until he died in 1985. She went on to become lead author of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s authoritative 1993 text on SIDS.

Molly Dapena hadn’t thought about the Noe case for years until approached by the authors of The Death of Innocents in 1995. I ask her if she feels that by helping the authors of the book, and now by speaking out more publicly about the Noes, she has redeemed past oversights.

“That had nothing to do with it,” she insists. “I don’t think I was trying to redeem myself. I was just trying to be helpful to people working on a project. If I can help people, I’ll do what I can.”

Is it possible that the result of your actions is to redeem yourself, as some of your colleagues have suggested?

“Well, I would rather trust their memories than mine,” she says.

Regardless of age-old sins of omission or commission, what was true then is true now. The status of the Noe case is likely to be changed only with a confession. There was no definitive physical evidence then, and there is little hope the bodies of the Noe children would yield any more useful information today. Several are buried in a Philadelphia cemetery that was somewhat notorious in the medical examiner’s office. After a hard rain, it wasn’t uncommon for the M.E. to receive a call about bodies washing up from their graves.

Once more, a sense of dread has returned to the Noe home. Following the death of their 10th child, the couple’s attempt to get on with their lives met with some relative success. After years of working in factories and serving as a local committeeman on the side, Mr. Noe was able to get a string of low-level political patronage jobs with the city. (He was an aide to Harry Jannotti, until the councilman was brought down by Abscam.) Marie, whose migraines disappeared after her hysterectomy, became a local committeewoman, and Art was able to help her get jobs at traffic court and the parking authority. They became more active in the church, and by their own admission grew much closer than they had been while having children.

But that life phase has ended as well. They are “in dire straits.” In one of our conversations, Mr. Noe says he has had a premonition he will die soon, eliciting a nervous laugh from Mrs. Noe. In a later discussion, Mr. Noe tells me he is thinking of killing himself. “My life’s been screwed up,” he says. “What the hell?”

The Noes recall feeling resignation when they were investigated 30 years ago. “No matter who dies or how they die, there’s always an investigation,” Mr. Noe says. “What can you say — ‘Stop, I don’t want you to’? The law states the coroner has the right to investigate. They come to the door and ask questions.

“That’s how I felt then. I can’t say what I’m gonna feel now. Ah, the hell with you. It’s over with. Let them think what they want.”

“People are gonna think what they think,” his wife agrees. “Sometimes you’d like to hide under a log, but what good is it gonna do? I know I often question myself about each one of them babies. … you feel it’s your fault, and you coulda prevented it because you were so tied up in yourself or something.” She rubs the back of her hand across her misty eyes. “I imagine every person that has a SIDS case thinks this way — “

Art interrupts. “You’re not responsible Marie,” he says. “It’s just something that happened.”

The last time I visit the Noes, the reality that their case is being reinvestigated has finally sunk in. Mr. Noe paces back and forth on one side of the dining room, punctuating his bitter monologue by pointing his cigarette, while Mrs. Noe stands perfectly still on the other side, interjecting a thought only when her husband pauses to take another drag. “If I killed them babies,” she says, “do you think we’d still be living in this same neighborhood, and have all these pictures of them up?”

Mr. Noe says he wants to know — if people are so goddamn interested in new theories about his dead babies, “What about killer genes, huh?”

Listening to this gaunt, haunted couple, I think about what Fillinger told the nun about the Noes over 30 years ago — that they have either endured one of the most horrific medical tragedies of the century, or they caused it. Watching the two of them brings to mind one of those winking Jesus postcards. As they rail at me, I move my head slightly, and the picture changes. From one angle they look like a sad old couple falsely accused, from another a sad old couple falsely exonerated. Mr. Noe is either a husband fiercely protecting his wife or a desperate man protecting himself.

From every perspective, they are sick with fear. They jump when there’s a sound from the street or a knock at the door. Sometimes it’s a neighbor, out of rehab, asking for a few bucks — nearly broke themselves, the Noes are still a soft touch — and sometimes it’s just the local free shopper being lobbed from a slow-moving delivery car. But one day soon, it will be a homicide detective knocking on their door. If he arrives before death does, they will have some explaining to do.

© 1998 Stephen Fried