Pasek and Pasek

With La La Land and Dear Evan Hansen, Ardmore native Benj Pasek is helping to make the musical cool again. But the real star of the family just might be his mother.

Benj and Kathy at the Oscars. Photograph courtesy of Lester Cohen/WireImage/Getty Images

It’s a Sunday evening in late September, and 32-year-old Benj Pasek — currently the toast of both Broadway and Hollywood — is on the phone, trying to explain to me that, yes, his life is busier and more chaotic than it used to be, but honestly, it’s not nearly as glamorous as you might think.

“Justin and I feel very lucky that we’re getting the opportunity to write every day,” he says earnestly, name-checking Justin Paul, his songwriting partner since college and collaborator on the current Broadway smash Dear Evan Hansen. “You know, we really just go into a room and we bang our heads against the wall, and we collaborate until we come up with the best work we can. For us, it’s a little more nerve-racking — and mundane — than it might appear from the outside.”

The subject of Benj’s busyness has come up, in part, because of the difficulty in scheduling an interview with him. A conversation that was originally slated for June got moved to a Monday in September, and then to a Sunday in September, and then was shifted from an in-person meeting in New York to a chat on the phone so that Benj — who grew up in Ardmore — could make it to the airport for a Sunday-evening flight. Success, it seems, does not come without scheduling issues.

Eighteen months ago, Pasek and Paul, as they’re known, were rising, if still somewhat obscure, young Broadway composers. Today, they’re among a handful of people helping to move the musical back to the center of pop culture’s stage. In January, the pair, along with composer Justin Hurwitz, snagged a Golden Globe for their song “City of Stars” from the movie La La Land; seven weeks later, the trio landed yet another statue for that song at the Oscars. Four months after that, Dear Evan Hansen — an affecting musical about teenage loneliness, loosely based on an incident from Pasek’s days as a student at Friends’ Central — cleaned up at the Tony Awards, in the process establishing itself as the biggest Broadway phenomenon since Hamilton. And things show no sign of slowing down: Up next are a live-TV production of Pasek and Paul’s stage musical A Christmas Story (airing on Fox on December 17th) and the December 20th opening of The Greatest Showman, a musical film about P.T. Barnum for which the duo has written the songs.

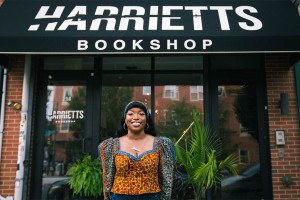

Meanwhile, in the midst of it all, Pasek also managed to go viral thanks to a heartfelt shout-out to his mother, Kathy, during his Oscar-night acceptance speech. “I want to thank my mom, who is amazing and my date tonight,” the fresh-faced Pasek said breathlessly as he stood at the podium in a tuxedo, looking like James Bond at his bar mitzvah. “She let me quit the JCC soccer league to be in a school musical. So this is dedicated to all the kids who sing in the rain and all the moms who let them!” The camera cut to Kathy, who stood glowing at her seat and waving at her son.

To the average viewer at home, it was a sweet moment between a grateful kid and his proud mother. To those in the know, it was something more.

For the past three decades, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek has been one of America’s foremost experts on childhood development — a Temple professor, a Brookings scholar, and the author of more than a dozen books on parenting, development and education. And the great theme of her work is one that aligns beautifully with the sentiment her son hinted at on Oscar night: that in our hyper-competitive, helicopter-parenting world, we’ve gotten way off track when it comes to what matters in raising and educating kids.

“I mean, both,” Benj says when I ask if his Oscar-speech reference to giving up soccer was meant literally or metaphorically. “I was definitely in the JCC soccer league for many years. And I actually loved it. Kobe Bryant’s dad, Joe, was one of my coaches. But I remember I definitely felt more of a pull to be in the plays and the musicals. And my parents were really supportive of me pursuing that passion.”

On the surface, it makes for a neat, tidy narrative: parenting scholar takes the principles she’s developed in her research, applies them to one of her children, and — voilà! — out comes a brilliant young man crushing it in his chosen field. But if you’re looking at the Paseks as a blueprint for how to turn your kid into an overachiever, you’re missing the point of their story.

On a rainy day in October, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, who’s 64, is sitting comfortably in the Ardmore home where she and her husband Jeff, a lawyer at Cozen O’Connor, raised their three kids. (Josh, the oldest, is a professor of communication at the University of Michigan; Mikey, the youngest, is a PhD candidate in social psychology at Penn State.) With short brown hair and bright eyes, she has the warmth and enthusiasm of everybody’s favorite kindergarten teacher. Which isn’t to say she doesn’t get exasperated. The object of her ire at the moment is the slew of high-tech parenting contraptions she’s seen of late, including one called the Babypod.

“It’s a new tampon-like device that a pregnant woman can insert so she can make sure the baby is hearing well before it’s born,” she says, those bright eyes all but rolling. “Now, you wouldn’t have that device if parents weren’t obsessed.” It’s not the only gizmo that’s got her goat. “There’s another new device to help with potty training where instead of just having a kiddie potty, you put an iPod in front and click it so the app can help your child.” She sighs. “I mean, are we kidding? Are we kidding?”

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek has spent much of the last couple of decades trying to get America’s educated, upper-middle-class parents — the folks most obsessed with churning out “successful” kids — to calm down a little bit, while simultaneously trying to identify the policies, strategies and tactics that can help all kids thrive. Much of her work has been scholarly, but twice, she and her frequent collaborator, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, have written popular books geared toward more general audiences. In 2003 they published Einstein Never Used Flash Cards, a research-backed argument for why play is vastly superior to academic drilling for toddlers; last year they came out with Becoming Brilliant, a blueprint for what education should look like in the 21st century. (CliffsNotes version: less focus on test scores, more on skills — from collaboration to creativity — that will help children reach their potential.)

“We’ve got a whole country that’s obsessed with the idea that success equals how well you do on your reading and math test,” she says. “But if you ask any parent would you rather have that or a happy, healthy, caring, thinking, creative individual … every parent chooses the latter.”

The style of education and child-rearing that Hirsh-Pasek promotes seemed to happen more easily in a less-stressed age. She remembers the freedom and encouragement she got from her family growing up in Harrisburg, whether she was inventing a new kind of bowling alley in her basement or — she swears she’s not making this up — planning to become a Broadway composer. “My mom and grandmother said to me, ‘Are you gonna do music? You’re so fascinated by it.’ And I said, ‘I’m gonna write a Broadway show.’ Most parents would have said, ‘Oh, you’re crazy.’ But my grandmother and mother said, ‘Then you will.’”

She ultimately chose a different path, getting a PhD in human development at Penn and settling into a teaching and research career at Temple. Studying childhood is an interesting way to make a living, since unlike in, say, economics, you can’t really leave your work at the office — at least, if you’re a mom. The thing you focus on during the day — kids — is the same thing you come home to at night. But Hirsh-Pasek insists the combination was valuable, less because she and her husband were applying research to raising their kids than because raising kids gave her ideas about research. Those ideas sometimes went against the grain. When the American Academy of Pediatrics issued an edict several years ago that no child should watch TV before age two, she pushed back: “I said to them, you know what, guys? Moms need a break. We have to make dinner. We have to take a shower. What do you expect of moms?”

In the midst of raising kids and doing research, she also found herself drawn back to her first love: music. When her three boys were small, she started writing songs from a kid’s point of view and eventually co-founded a group called Kamotion that over the course of several years played concerts and recorded five albums. Kamotion’s peak came in 1994, when they were invited to perform at the annual White House Easter Egg Roll.

One of the guest soloists in their set? Nine-year-old Benj Pasek.

Benj believes it’s no accident that the musical — in the form of Hamilton and Glee and Frozen and, yes, La La Land and Dear Evan Hansen — is finding new life these days. After all, the first movies he and his fellow millennials paid attention to were the animated Disney musicals scored by Alan Menken. “It makes a lot of sense, if The Little Mermaid is the first movie you ever see, that you have an appetite for musical content in a way that previous generations didn’t,” he says.

Kathy insists she had no particular inkling her middle son was headed for musical success: “Did I know he was a smart kid? Sure. But everybody has a smart kid. Do I personally like his melodies? Yeah, what Jewish mom wouldn’t like her kid’s melodies? I wish I could tell you I’m prescient. I’m not.”

In truth, it took a proverbial village to help Benj develop his musical abilities. He credits a trio of teachers at Friends’ Central for exposing him to sophisticated music and theater while he was still young (Sondheim! In middle school!), as well as his friendship with Justin Paul, which began during their summer orientation at the University of Michigan. (Not helpful: the high-school piano teacher who, Kathy says, “fired” Benj as a student because he didn’t like to practice. Hope she enjoyed the Tonys.)

After writing a song cycle as undergrads at Michigan, Pasek and Paul moved to New York in 2007 to take their shot at show biz. They fairly quickly … succeeded. Over the course of a half dozen years, they wrote for the NBC show Smash, composed the score for a new musical version of James and the Giant Peach, created an off-Broadway show called Dogfight, and finally hit the Great White Way with a musical adaptation of the holiday cable hit A Christmas Story, which was nominated for a Tony in 2013.

It was that same year, on a trip to Los Angeles to meet with writer Steven Levenson, that they began working in earnest on what would become Dear Evan Hansen. The idea grew out of a memory that had stuck with Benj for years — of the way he and others reacted to a fellow student’s death when they were at Friends’ Central: “I was always really interested in why so many of my peers, and why so many in the school community, felt the need to be so public in their grieving. And I was just as complicit in this as anybody else.” Also on his and his collaborators’ minds was the way their generation had dealt with 9/11, including the fact that some people lied in their college entrance essays about connections to people who died that day: “We were sort of struck by why particularly people of our generation were so keen on inserting themselves into a tragedy that they had no place being part of.”

In Dear Evan Hansen, the title character is an awkward teen with severe social anxiety and few connections to other people, including his parents (a feeling of loneliness captured achingly in the song “Waving Through a Window,” with its refrain: “I’m tap, tap, tapping on the glass/I’m waving through a window”). When Evan inadvertently exaggerates the friendship he had with another student, Connor, who has died by suicide, his popularity and social status skyrocket. What’s fascinating about the show is the way it takes a dark, cynical situation and flips it on its head. “Tragedy, oddly, allows us to be openly emotional and connect to a community,” Benj says.

Dear Evan Hansen debuted in Washington, D.C., in the summer of 2015, not long after Pasek and Paul began working on songs for La La Land. The movie opened across the country last December, and that same month, Dear Evan Hansen premiered on Broadway. Two months after that, Benj was onstage at the Oscars, saying thanks to his mom.

Dear Evan Hansen is a show very much of its time, but in the end, maybe not surprisingly, it’s also a story about something more universal: the relationship between parents and children. Some of the show’s most powerful moments are when Connor’s parents try to come to terms with their son’s suicide, and when Evan’s mother fully understands how absent she’s been from her son’s life.

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek says one of the dangers we face when raising kids today is exactly that: missing the moments when we can truly connect with our kids in a human way. The problem with potty training your kid through an app, in other words, isn’t the app; it’s the missed opportunity to look your kid in the eyes.

She describes a study that she and some colleagues at Temple recently did in which they asked parents to teach two new words to their two-year-olds. While one word was being taught, the study’s authors did nothing; while the other word was, they interrupted the parents with a cell-phone call. The kids learned the first word just fine. The second? Not so much. “It’s almost as if we’ve lost the human connection,” Hirsh-Pasek says. “And you know, I think Benj tapped into that in Dear Evan Hansen — that you’re tap, tap, tapping from the outside, looking in.”

Hirsh-Pasek has two big initiatives she’s focused on. One is continuing to push out the education ideas covered in Becoming Brilliant. The other is Learning Landscapes, an initiative that attempts to create more moments for creative play — and parent-child interaction — in low-income areas. (One project, Playful Learning City, is funded by the William Penn Foundation and under way in West Philly.)

Her middle son, meanwhile, in addition to this month’s premieres, seems to have come full circle in his creative life. He and Justin Paul are now working on two upcoming Disney live-action movies, Snow White and Aladdin. Their collaborator on the latter film? Alan Menken.

“We still get nervous to be in the room with him,” Benj admits. “But he’s such a warm and kind guy, and it really feels like getting to be in the room with your hero.”

Which is not to say he only has one. “She was the best date a boy could have dreamed of,” Benj says of Oscar night with his mother. “My mom had to be my date. She was the person who was always by my side.” It’s a reminder of the impact we make as parents, one way or another.

Published as “Characters: Pasek and Pasek” in the December 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine.