Jeffrey Lurie’s Long, Strange Trip

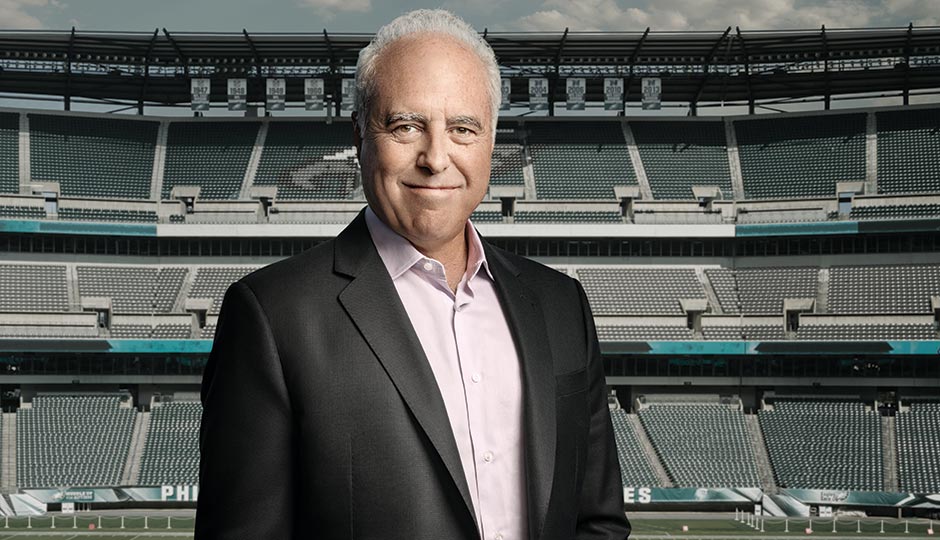

Photograph by Chris Crisman

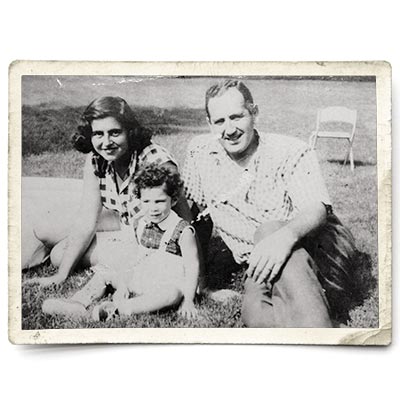

One warm, crystalline July day outside Boston, Jeffrey Lurie stands before his father’s gravestone in order to share his thoughts, to commune with him. Morris Lurie died in 1961, when Jeffrey was nine years old, and Lurie comes to visit him every year. This year, Jeffrey made the trek to Temple Israel Cemetery just before his football team’s preseason got under way.

As always, Lurie silently tells his father how his mother and younger brother and sister are doing, and how much he loves his second wife, Tina. Now, in sharing what he imagines saying to his father, Lurie chokes up a bit: “Which reminds me of him and my mother. I feel that I’m replicating that, and I want him to know that. And I’ll talk to him about the football team. I don’t go through every player, but I’ll let him know how excited I am about the team. … Oh, and I’ll go through my kids” — a daughter and son in their early 20s. “I don’t do much more than that. If a dog passed away … I was really sad about losing Satchel” — named after both Negro League baseball star Satchel Paige and onetime Boston Celtic Satch Sanders. “My other dog I named Wrigley” — after the Chicago Cubs ballpark. “I like the field.”

Sports — Lurie laughs about how often his mind rockets there, even when he stands before his father’s grave. Or especially when he stands before his father’s grave. He was very close to his father, and sports was their primary connection. And then sports got even bigger, in the wake of his father’s death. Lurie played tennis and baseball, but playing wasn’t really the point; watching — becoming an obsessive fan of Boston’s teams — was. His mother, Nancy, let him skip school on the day of the NFL draft when he was a teenager, as if it was a national holiday. Sports was a way to keep his father alive and a path, too, into a parallel world, a method of survival after what he had lost. An escape.

Now, standing before his father’s grave, Lurie wonders what more Morris wants to know. One thing is that Jeffrey is a good person, an annual assurance on humility that he gives. “I tell him that I walk around as Nancy and Morry’s son,” Lurie says. “I tell him, if you had a machine on me that could tell you what I’m thinking as I walk around Philadelphia, I rarely walk around as the owner of the football team.” Lurie is phenomenally rich, and a sophisticated man — he has a doctorate in social policy from Brandeis, spent time in Hollywood producing movies and has traveled the world — but in his telling, he’s a simple one: “I kind of became an adult at age nine, but you’re kind of always a kid. You shouldn’t try to lose it.”

Jeffrey Lurie knew where he was headed early on. Long ago in Boston, he met a boy named Joe Banner who was also obsessed with sports. Jeffrey told Joe that he would one day own a sports team, and Joe said he would run it for him. They were right, of course — Banner would end up as Lurie’s longtime right-hand man with the Eagles — though at the time of their pronouncements, neither was old enough to vote.

But Lurie’s goal was never simply to own a team. Norman Braman — remember him? — who sold the Eagles to Lurie in 1994, was a mere owner; Braman didn’t know defensive end Reggie White from the water boy and bled the Eagles dry. Lurie’s interest is different. He has now owned the Philadelphia Eagles for 23 years. For the first decade or so, the Eagles tracked upward — a cool new stadium was built; the 2004 team under coach Andy Reid went all the way to the Super Bowl — but since that loss in Jacksonville, things have gotten … interesting. Meaning messy and at times odd, and not so successful. Two years ago, when his team under coach Chip Kelly was imploding, Lurie went to every player in the locker room before a game against New England to say: “They beat us in the Super Bowl. I want to fucking beat them today.” That win was the lone bright spot in a lost season.

Last year, Lurie hired a new coach and realigned the front office. He says now, as he’s been saying for some time, that he’s sure his football team will win a championship. “It’s personal,” he says. And then he says it again, to make it clear how important this is: “It’s personal.” He doesn’t know when, but he has no doubt it will happen.

This is bold and risky territory, given that for so many Philadelphians, the Eagles aren’t an escape or entertainment or a fancy metaphor for grappling with life’s harsh realities. The Eagles are reality; we feed straight off the teat of the team’s success. Or failure. Jeffrey Lurie certainly feels our pain. But our pain isn’t his primary concern, given that for so long, he’s been driven by an obsession all his own.

Later that afternoon, after leaving his father’s grave, Lurie visits his childhood home, a handsome brick colonial in West Newton. He gets out of the car and points to an upstairs window, to the room where he and Morris communed in flesh and blood: “There it is!” he says. “We watched football in there. On a little black-and-white TV.” Until the day Jeffrey came home from school to see his house surrounded by what seemed like 50 cars, and someone said to go upstairs to see his mother, who told him that his father was dead.

“He lives good rich,” Andy Reid once said of Jeffrey Lurie. Lurie’s main residence, a 13-acre spread in Wynnewood, was the estate of media baron Walter Annenberg; it sports a three-hole golf course, a bowling alley, a lap pool and a greenhouse, plus woods and a creek. Lurie also has lush homes in South Florida and on Martha’s Vineyard. He travels in a private plane. When he vacationed in Rwanda last year, he met with President Kagame, to whom he’d been introduced by financier Evelyn de Rothschild, who summers across the street from Lurie on the Vineyard. It’s a large life.

He’s a curious man, though — friendly and accessible, not high-handed at all. Yet when I meet with Lurie in his office at the NovaCare Complex, he seems nervous, despite the several hours we spent together in Boston. He shows off photos: his kids skiing, shots of players, basketballers Dr. J and Larry Bird — “I got friendly with Julius; I still am. And his ex-wife Turquoise” — an autographed album from Glenn Frey of the Eagles (get the connection?), a signed verification of the 385-yard golf drive he hit in Ireland, with a little help from the wind. Lurie lands, finally, on a photo of one of the Boston Celtics teams from his youth, an informal locker-room shot of Bill Russell-era title winners gathered around their coach. “It’s an aspirational thing,” he says. “No one will ever match this. I take from this how they were teammates. When I pass by this photo, it’s not about the Celtics — it’s about teammates.”

It’s an odd moment. Lurie is nervous because he needs me to understand something. He was no ordinary fanboy; sports centered on what was important, on values that he has to live up to, on how he must run his team. He needs me to see that, which is new for Lurie: For better than two decades, he’s stayed at a slight remove — at a distance, that is, from us — and letting anyone in like this is new.

From the first day he set foot in Philadelphia, Lurie was met with a strong reception. There were E-A-G-L-E-S chants in restaurants when he entered; he couldn’t walk down the street without somebody racing up to him and yanking up a sleeve to show off an Eagles tattoo. “It’s still wonderful,” Lurie says of fans’ reactions to him — yet he quickly morphed, long ago, from an owner who was out and about a great deal and accessible to the media to one we rarely hear from. I ask Lurie if he ever listens to sports talker WIP, and he laughs: “You can’t.” You can’t take in all that negative noise. But Lurie says that Philly’s rabid fans understood him from the beginning: “That I was a fan buying the team.”

Yet he made an early decision to stay out of harm’s way; one longtime insider calls him very thin-skinned. So Lurie typically gives a state-of-the-team address once a year and pops up to make a statement when important or bad stuff happens — quarterback Michael Vick gets signed after doing time in prison for running a dogfighting ring, or coach Chip Kelly implodes and has to be fired — then seems to disappear again. Joe Banner and then Howie Roseman have been his consiglieri on the football side of the business, the guys he has needed to run his team day to day, which puts them, not Lurie, in the crosshairs of fan frustration. Or rage.

But Lurie’s caution means that at this point, we really don’t even know his role with the team.

Lurie with Carson Wentz. “It was all of our obsessions, especially mine,” Lurie says of the quest for a franchise quarterback. Photograph by Chris Crisman

He delegates. Lurie and Roseman and ex-staffers all say the same thing: Jeffrey’s in the room on draft night, he’s part of decisions with big free-agent signings, but even with a head-coaching search, which is his final call, he listens and asks questions and wants help. He doesn’t dictate — and, in fact, Lurie claims never to have overruled a draft decision by his lieutenants, which Roseman and others confirm. Before last year’s draft, Lurie flew out to North Dakota with Roseman and coaches to vet Carson Wentz as a possible pick. “It was all of our obsessions, and especially mine,” Lurie says. “Is this the year of the franchise quarterback? Carson was the third one we saw on the trip, and even just the first hour, it was a whole other persona. He was a very poised, upbeat, sharp, committed, driven, confident, genuine guy” — yes, the fanboy is alive and well. “At 22.”

So was Wentz his pick at that moment?

“That started a day-and-a-half process — there was a classroom part. I’m watching, and going to see how the coaches feel.” In the end, the Eagles did choose Wentz, of course, but not because Lurie ordered it. It wasn’t his decision to make.

He’s not like the Cowboys’ Jerry Jones or the Patriots’ Robert Kraft, self-made businessmen who rule their football fiefdoms with only themselves to please. Lurie’s money came from family. He believes he has to handle himself, and his team, in a certain way. It’s a style of leadership that was set in motion long ago, when he was a young boy — that’s the point of sharing the picture of his beloved Celtics, of lauding their teamwork.

It’s also why, in comparison to the overlords, he whispers.

Jeffrey Lurie’s sunniness seems preternatural in spite of the early loss of his father from kidney cancer, though he’s given his mien a conscious boost. “My attitude was to live,” he says. On the day he went to visit his father’s grave, we tooled around Greater Boston, his driver taking us to Brandeis, where Lurie got his doctorate, not because there’s any particular point in seeing Brandeis — but so that Lurie can share his life as a young man. It’s a part of his story he’s at ease with.

There was money — Lurie’s grandfather on his mother’s side had founded General Cinema, which became one of the country’s largest movie-house chains. But there were struggles, too. Lurie’s younger brother is autistic, and throughout their childhoods was barely able to communicate. And the whole family had a tough time when Morris Lurie passed away.

Still, the money allowed Jeffrey a certain freedom when he went off to Clark University. He sported a Jew ’fro, drove all over the Eastern Seaboard in a red ’69 Firebird convertible with a black interior, followed the Grateful Dead around New England, camped all night outside Boston Garden for hard-to-get tickets to the Bruins or Celtics, and pursued girls at Clark after breaking free from an all-boys private high school in Cambridge.

Lurie as a child with his parents. Photograph courtesy of Jeffrey Lurie

There was freedom, too, to draw up his own plan of who he might be, in the early ’70s. “I knew I really wanted to understand human behavior,” Lurie says, lounging in the backseat of our rental, not bothering with a seat belt. “I think my biggest focus at that time was psychology and what’s going on in the world — what was taking place with American foreign policy and domestic policy. And something else that was happening, that I absolutely believe in — women’s liberation happening at the time was a validation that we’re all the same.” Lurie has the agreeable presence of, say, a sociologist. Though one who wanted to make a large dent in the world somehow, starting at Clark.

One brainstorm was to create a huge charity concert that would raise money for preventive medicine, especially heart disease and cancer — Lurie and his roommate, Steve Bahn, were contacting legendary promoter Bill Graham and getting bands like Three Dog Night and the Dead on board a decade before Live Aid. The American Heart Association was interested, and the Astrodome in Houston was all but booked before the AHA backed out, fearful that the idea might come across as a little too cutting-edge. Another Lurie idea cooked up with Bahn, post-college: to create videodiscs that would capture cool places to travel to, a pre-Internet tool for travel agencies. Lurie hired videographers to make a demo of Boston, but the venture went belly-up over production problems.

One large idea did take off: creating a free university at Clark. The course offerings there were limited — why not open up the possibilities for evening classes and offer them to the community as well at no charge? The administration got on board and gave Lurie and Bahn an office, where they created a syllabus that expanded to dozens of schools all over the country.

But the world as his oyster created a small problem, post-college, for Lurie — what to do? Given that 22-year-olds don’t buy NFL teams.

Lurie went to grad school in psychology at Boston University with the thought of becoming a practicing psychotherapist. But dealing with eight or 10 people and their problems, he found in training, was too limiting. “My thoughts were about a bigger world,” he says. He wanted to check out a third-world country, so he spent several months in Cuernavaca, Mexico, at a social-policy institute founded by Ivan Illich, who wrote Deschooling Society. Lurie volunteered at a center for abused women and got fluent in Spanish. Then he taught social policy for three years at B.U., where he could launch into the morass of big issues: the policies leading to the American invasion of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, for example. Or genital mutilation in Senegal, which is easy to be opposed to, not so easy to figure out how to solve.

“Some people are deal junkies,” Lurie says. “I’m an analysis junkie.” But teaching proved too constrictive as well. “It comes back to being boxed in. It felt limiting.”

Lurie had also started a doctorate at Brandeis in social policy. His first idea for a dissertation was “The Politics of Intimacy.” It was a larger-than-life idea, though it requires some explanation from undoubtedly the first owner of a professional sports team who talks like this:

“I really enjoyed reading certain psychoanalysts, one of whom was very controversial, named Wilhelm Reich. And it raised the question to me, are we organizing societies to maximize people’s fulfillment of the need for intimacy? We have kind of a patriarchal system. We have a lot of different pressures of how people should be sexually. You’re born into a certain social structure, with variations depending on where in the country you are — let’s kind of redraw the map. What would be best for society? Are the savages in the Malinowski study” — a reference to The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia, written in 1929 — “happier? What should we be looking at? Countries like Sweden and Norway, Scandinavian countries? Should we look at Communist countries and see what’s happening there?”

Not surprisingly, Lurie couldn’t get this idea focused into an actual topic and would end up writing a dissertation on the role of women in Hollywood movies.

In the early ’80s, not long after he turned 30, Lurie spent two years learning the family business — perhaps it was time for General Cinema to buy a movie studio, and perhaps he would run it. But what he really wanted to do was make movies. Now, here was something large enough, with grand possibility: “Ideally, I would make some movies that have a true social consciousness,” Lurie says.

Except not in Hollywood. Lurie produced seven movies in his decade there, including, infamously, V.I. Warshawski, in which Kathleen Turner played a detective whose stunt double wore a red wig, though Turner was blond — a screwup emblematic of the movie generally. “I found that unless you were one of a handful of people — Spielberg was one, Lucas another — you really had almost no say on what would get financed,” Lurie says. “My favorite ones never got made.” He wanted to make a film about AIDS, for example — on what created the virus and the crisis. He did a huge amount of research. He pitched and pitched, trying to drum up the financing. All for naught.

Near the end of his time in Hollywood, in 1992, Lurie got a call from his mother. She told him to get home to Boston, right away. She’d found an autism expert for his brother, one who’d arrived at the Lurie home with a rudimentary keyboard. Lurie’s brother had never really spoken, though he could sing — mostly show tunes and the Beatles. But as the facilitator touched Jeffrey’s brother on the shoulder — something about the touch was integral to what happened next — he could type out his thoughts rapid-fire. Suddenly, at age 37, he had language.

When Jeffrey arrived, his brother typed: Jeffrey, I’m not stupid. And: Jeffrey, I love you so much sometimes it hurts.

With that, half a lifetime of thoughts poured out.

“We spent the entire night, all night, just having him communicate,” Lurie remembers. “It was unlimited — his experiences, at different schools. The loss of our father — that was one of the main things he wanted to discuss. Soon after my father died, he was sent to a school. He wasn’t able to be with all of us and go through the stages of grief. He talked about that that night — the isolation and loneliness.”

Lurie’s time away, pursuing whatever he wanted, searching for his place in the world, was about to end. By this time, the family business had morphed: General Cinema had become the largest independent Pepsi bottler. Uncle Richard sold that part of the company for $1.7 billion and bought the publisher Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, then merged his two companies into a conglomerate worth $3.7 billion, with 23,700 employees. Which made Jeffrey Lurie not just rich, but filthy rich.

Something else was new, too: In California, Lurie had met Christina Weiss, who co-produced one of his films, I Love You To Death. Her father was a Philadelphia-bred businessman who’d struck it rich mining manganese in Mexico; Christina had been educated in Europe. Lurie fantasized, an old friend says, about becoming more cosmopolitan, “and there she was to take him there.” They married in 1992.

The experimental part of his life was over. One Sunday in the early ’90s, as he watched an NFL game, Lurie turned to a Hollywood buddy, Jeffrey Auerbach, and told him, “I really want to buy a team.”

Auerbach knew Lurie’s family had money; he had no idea how much. “Shut up and watch the game, Jeffrey,” he said.

Jeffrey Lurie paid more for the Eagles in 1994 — $185 million — than anyone had spent on a sports team, ever, the stupidity of which the Wall Street Journal immediately noted in a front-page story. But Lurie saw something everyone else seemed slow to recognize. He casts it in Hollywood terms: Everybody there was desperate for the next blockbuster, while here was the NFL creating all these dramas — the games! — that people would watch in droves. TV’s continued growth, he believed, meant that revenue from programming rights was about to shoot through the roof.

He was right — the Eagles are now worth an estimated $2.5 billion — but Norman Braman had left the team in such a state that the Journal’s analysis appeared to be spot-on. Rat-filled Veterans Stadium was awful; the team had a lousy practice facility; the scouting was bad. Braman had recently unloaded the best players — including Reggie White, who in heading off to Green Bay for a boatload of cash left in his wake the idea that Philadelphia wasn’t exactly a good landing spot for high-priced athletes, especially if they were black.

It was, in the beginning, a mess. But Lurie made two big hires that would set the course: Joe Banner and Andy Reid.

Banner, Lurie’s childhood friend, who’d made a small fortune in a chain of men’s clothing stores, would run the team day to day and serve as Lurie’s conduit to it. And Lurie and Banner would bring creative thinking to pro football; they were smart guys who had the advantage of not being encumbered by the old-school NFL, since they had no idea how things had always been done. They’d figure it out. First, a hiccup: They hired Ray Rhodes, a hard-as-nails African-American coach who was great at rallying the troops and gave the team a bit of racial street cred. Alas, Rhodes didn’t much care what happened beyond the next game; building a team for the long haul wasn’t in his arsenal.

They then made an outside-the-box move that would set the course of Lurie’s tenure: He and Banner tapped Andy Reid as coach in 1999, for all intents and purposes beginning the Lurie era. There is something of a dispute, now, on who discovered Reid — Reid’s agent says it was Banner; Jeffrey Lurie says he’d had his eye on him for some time before he was hired. Regardless, Reid was a leap of faith.

No NFL team had ever hired a head coach who hadn’t run a college team or overseen an offense or defense in the NFL. An impressive coaching résumé was deemed crucial. But Lurie and Banner challenged conventional wisdom: Why not Reid, who showed up to interviews with voluminous notebooks that sketched out every facet of running a team?

Lurie showing off the 2005 NFC championship trophy, a franchise high point; bonding with passionate Birds lovers. Photography courtesy of Jeffrey Lurie

When he talks about Reid now, Lurie taps not just the winning — under Reid, the team had its best decade on the field ever — but something that seems just as important to him: “He is terrific, a terrific coach and human being. … His attention to details, creative offense, respect of the players, how he was terrific with everybody in the building — he represented my values 100 percent.” Reid might not have shared Lurie’s academic mind-set or kumbaya worldview, but they connected on another level. “He treated the janitor the same as the quarterback,” says Lurie. “That’s me.”

Andy Reid was Lurie’s nerve center, the buck-stops-here presence he needed. The guy to create the kind of team — not just a winning one — that Lurie craved. One day in the summer of 2009, Reid called Lurie: “I’m thinking of signing Michael Vick as our third quarterback.”

Oh, brother — Vick had just been reinstated by the NFL after doing time in prison for his role in a dogfighting ring in his hometown in Virginia. Reid’s request immediately challenged Lurie’s method and values. The pure cruelty of dogfighting made Vick … well, what did it make him? Especially to a dog lover like Lurie. He couldn’t delegate this one. He would have to decide.

Lurie had Vick come to his home in Wynnewood and looked into the quarterback’s eyes. He says he saw true remorse. What’s more, Vick had spent his time in prison reading a great deal and learning to play chess. That night, Vick and Lurie’s son, Julian, who was a teenage chess whiz, had a marathon match. “Michael was competitive and warm and enjoyable,” Lurie remembers. “It could have been an act. But I believed in the guy.”

After Vick was signed, the reaction was intense: The Eagles were whores, some said. But later that year, Lurie got a call from President Obama, congratulating him on the step he’d taken. Giving Vick a second chance sent a certain signal, Obama said, “and I know it wasn’t easy.”

Lurie says it was the hardest decision he’s had to make in his 23-year tenure as Eagles owner. “But part of making it was the trust I had in Andy. If he were a young coach not experienced in the machinations of 53 players” — if he couldn’t handle, in other words, whatever came his way in the locker room — “I wouldn’t have done it.”

In 2011, two years after the Vick signing, Lurie turned 60. He insists there was nothing magical about the number — no midlife crisis, no heightened sense of impending mortality — but within the next two years, he made several dramatic changes in his life. It felt as if Lurie was still searching for something, as he severed ties with three of the people he’d been closest to over the previous two decades.

Among them was Christina; they announced their divorce in the summer of 2012. (Daughter Milena, 24, is a filmmaker in New York; Julian, 22, graduated from Harvard in June.) Christina had always been demanding and intense — the polar opposite of Lurie in style — and in the later years of their marriage, it was clear to many that the relationship was broken. “They never should have married,” says Dan Kaplan, a lawyer who helped broker Lurie’s purchase of the Eagles and then repped Christina in the divorce. “Jeffrey really needed a much more placid, gentle, loving human being. Because he had so much pain as a child. If you know anybody whose dad died when they were young … ” Kaplan’s thought trails off, but his conclusion is obvious: Lurie needed support in marriage that he didn’t get from Christina.

Lurie’s second wife, Tina, whom he married in 2013, is Chinese. Her family, refugees who came to Philadelphia from Vietnam in the ’70s, opened a small grocery store in West Philly and eventually two Vietnamese restaurants; Lurie met her when she was working at Vietnam Restaurant. She flew with Lurie to Boston for his July trip to his father’s cemetery, a palpably warm and soft-spoken presence. At lunch that day, after Tina had gone off in a cab, Lurie ordered pizza, laughing gently that he’d fessed up to her about how he was temporarily going off his low-carb diet — as if he could ever hide such a thing from Tina. She is a sea change for him.

A few months after Banner’s departure, Lurie made the painful decision to fire Reid. In the wake of the Eagles’ Super Bowl loss in 2005, the momentum had shifted. The team’s play was inconsistent; they weren’t even getting close to the big game. At the end, Lurie had all the team’s personnel assemble in the NovaCare Complex cafeteria, then brought Reid in to a standing ovation (which was filmed and circulated online — a great calling card for the Eagles and Reid both).

To replace Reid, Lurie turned to Chip Kelly, then the shiny new toy in the coaching world — a college coach whose teams played at a pace that simply wore out their opponents. Kelly talked a good game of bringing his cutting-edge methods to the NFL, and Lurie — forever the analyst — lapped it up.

After Kelly did well in his first two seasons, Lurie gave him the full personnel control the coach had demanded, announcing publicly, “What we didn’t know is what a great leader [Kelly] is … I think what people don’t realize is how great he relates to players and his coaching staff, and it’s just very special.”

There was a problem, however: Not a word of that was true. Kelly tended to treat people, when he bothered with them at all, dismissively; he’d pass players in the NovaCare hall without bothering to acknowledge them, and he controlled various off-field aspects of players’ lives as if he were still running a college program.

Given a chance now to acknowledge that his comments about Kelly were spin, or overwrought, Lurie doubles down instead. “I meant what I said,” he claims in his office. Which corroborates something that has puzzled Eagles insiders over the years: How can a smart guy sometimes seem so clueless?

In contrast to Kelly’s first two seasons, his third year was a disaster. Not just because he started losing, but because he was losing so badly that the team was clearly going off the rails from within. Which is why Lurie went to the locker room before the New England game that December to implore each player: They beat us in the Super Bowl. I want to fucking beat them today.

By the time Lurie fired Kelly three weeks later, before the last game of the 2015 season, he clearly understood — there were Chip factions, anti-Chip factions, and a general sense of disarray. Teams are fragile structures. LeSean McCoy, a black star jettisoned in a trade for an injury-prone linebacker, has alluded to Kelly having trouble relating to black players. There’s no evidence for that, but it suggests just how uncomfortable the locker room had become, which was about as far from Andy Reid as a team could get.

And far from someone else. Once, when Jeffrey Lurie was about eight years old, he was in the backseat of the car with a friend, being driven somewhere by his father. He doesn’t remember where they were going or what he was talking to his friend about, but suddenly his father turned and said, “Jeffrey, don’t you ever be a bully.”

Advice to live by. No one accuses Lurie of being a bully. But somehow he had hired one to run his team, which maybe was just as bad.

A Super Bowl title is still Lurie’s white whale, though it’s clear that the win itself isn’t enough; he needs to do it in a certain way.

Many NFL insiders were surprised when the Eagles hired Doug Pederson to be their head coach before the start of last season. Lurie is adamant that the Eagles always hire top-notch talent, and just as clear that the best coaches “combine the cerebral with the visceral. Those are the really good coaches.” But Pederson is inexperienced and doesn’t have the intellectual heft of strong pro coaches. As Lurie began searching for a new coach, Pederson, who had been a backup quarterback for the Eagles two decades ago, did have one extraordinarily important guy in his corner: Andy Reid, with whom Lurie talked frequently. Pederson was working for Reid in Kansas City as an assistant coach.

“Going into the search, I said to my wife, it could evolve that Doug is number one,” Lurie says. “If Andy gives incredible reviews and goes through in detail with me how he would be as head coach, he could emerge as the number one candidate.” Reid obviously gave Pederson a big endorsement, and when I contact him now, he says glowing things about his ex-assistant. Yet Reid also shares his surprise when he got a call from Lurie saying he was interested in hiring Pederson as head coach. “Whoa,” Reid remembers thinking. “He’s their guy?”

At any rate, like Reid, Pederson has a crucial attribute: He’s a very nice guy — or, in the current parlance, he is blessed with emotional intelligence. And maybe Pederson, who had a so-so first year, will turn out to be a fine coach, though he’s not exactly inspiring comparisons to Knute Rockne. But he has done something very important, which is to allow Jeffrey Lurie to take back control of the culture of his team. Whether that leads to the NFL championship, no one knows, even as Lurie continues to assure us that his team will get there.

It’s still his obsession. Yet given that he’s a complicated man, with that doctorate and teaching and moviemaking on his résumé, a guy who spends his off-season traveling the world, is there anything more Lurie wants to do, other than win a Super Bowl? Anything that still touches on the bigger world he talked so enthusiastically about in Boston?

Lurie has an answer, both for himself and, it seems, for his far-off past. If his father’s sudden death was the seminal event of Lurie’s childhood, his brother’s autism was another pocket of great trouble and pain.

For a long time, Lurie has studied and funded autism research and clinical programs; his family’s foundation has contributed more than $75 million to various institutions. This summer, the Eagles announced they were sponsoring a bike-riding initiative to raise money for and awareness about autism. When Lurie talks about autism, about how it’s such a complicated, multi-disciplinary, “heterogeneous” condition, how CHOP and Jefferson and Drexel are all doing unique research to try to crack the problem and how he wants his bike initiative to become as big as the Jimmy Fund has been in fighting cancer, Lurie the intellectual and Lurie the young entrepreneur and Lurie the big-problem-solver reemerge. “It’s personal,” he says. Again. These days, his brother is doing well, pursuing two passions: music and abstract painting.

Lurie’s friend John Middleton, the Phillies owner who’s used his own wealth to get deep into various philanthropic causes, sees Lurie’s autism initiative as a big step forward. “Jeffrey has done a lot in philanthropy, but privately,” Middleton says. “This is going to be a change. This venture I see as kind of a melding of Jeffrey’s private life and his public life.” Which, Middleton believes, will lend Lurie’s giving far greater traction.

Jeffrey Lurie is, by any measure, the finest owner the Philadelphia Eagles have ever had. That might be damning him with a low bar. But given that decade of the best football in the organization’s history, and the stadium he built, and the Eagles’ commitment to local charity, he tops the list.

And Lurie leaves no stone unturned when it comes to sharing his methods; the Eagles are run a certain way by Morry Lurie’s son. Down to his parting words in his office, as the late-afternoon summer sun has grown softer on his team’s practice field, Jeffrey Lurie needs us to know: “I love my relationship with Troy, the janitor here. He’s a great guy. And the kitchen help. It’s how I grew up.”

Though Morris Lurie — like the rest of us — will still want to know, when Jeffrey visits his grave next summer: Just when will he deliver his team to the Promised Land? When? It’s coming, Jeffrey will tell him. Absolutely nothing changes that.

Published as “Jeffrey Lurie’s Long, Strange Trip” in the October 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine.