The Trials of Tony Luke

Three months after his son’s death from a heroin overdose, Tony Luke Jr. is grieving — and simultaneously battling his own father and brother in court. It’s a family drama whose roots lie deep in their South Philly pasts.

Photography by Gene Smirnov

It’s Monday afternoon, and Tony Luke Jr. drifts just above the surface of the moon.

A woman speaks into his earpiece.

“Anxiety is constant fear. Fear of your past choices,” she says.

Earth looms into view, blue and distant, and Tony Jr. whispers, “It’s beautiful here.”

The woman doesn’t hear. “Fear is a hummingbird,” she says.

He gives a flick of his hand and plunges under the sea. Then into a cave. A jungle. The moon again.

“Anywhere but here,” he whispers.

The virtual-reality goggles hug his head as he looks left, toward Saturn. He spent thousands of dollars on the technology to use it for games with his sons, but the oldest — Tony III — isn’t here, and never will be. He died in late March, at 35, of a heroin overdose. His demise will seem familiar, among the crowd of people shuffling daily into opioid addiction. But like each of them, to his family he was utterly unique: tender, conflicted, infuriating, afraid.

His death laid waste to the elder Tony. And waste is unfamiliar to a man who became famous for his liveliness, his loudness, his sheer largeness. Together, he and his father had built a mini-empire selling Philadelphia’s most famous product, the cheesesteak, and along the way, Tony Jr. grew — in personality and physicality — to embody the city, first reflecting it back to itself and later to the nation. He had prolific tattoos, a gleaming head, and a rasping South Philly accent that played well on television. He made himself into a human being, Whiz wit’.

Now the empire is crumbling from within, and he hardly cares. His once-meticulous goatee crawls across his jowls, and his sweatshirt stretches to contain his midsection. He spends his time stuck in a recursive loop of guilt, pondering his sins as a father and those of his father before him, and his father before them all: four generations of South Philly men all striving to flee the preceding generation and never quite making the slip.

Now Tony Jr. uses the virtual-reality machine for meditation and escape.

“To be at peace, you must be in the present,” the woman says.

But Tony isn’t in the present. The present is painful: him, sitting alone in a white-walled room. A room barren of any decoration or furniture except his chair, his virtual-reality goggles, and the computer that powers them.

A window looks north, on the Delaware River. Tony’s high-rise condo extends directly over the water, so that from his perspective the river is a silver ribbon stretching from beneath his feet to the horizon. A breeze has just driven away a squall, and the sun plays across the waves.

It’s beautiful.

“Anywhere but here,” he says.

The original Tony Luke’s location on Front Street and Oregon Avenue in South Philly. Photography by Gene Smirnov

The story that leads to Tony III’s death starts long before his birth. It starts with old Armando Lucidonio, who emigrated from Italy to Philadelphia four generations ago.

He was a large man, more than 500 pounds, with fists like bags of cement. He swung them often.

He had an immigrant’s work ethic and fastidiousness with money. He kept each dime and dollar in a can assigned to its purpose: the grocery can, the rent can and so forth. Once, when the insurance man came around the apartment early to collect, Armando discovered his wife had slipped a few quarters from that can into another one, to cover an expense.

He beat her so severely, and so immediately, that the insurance man was still in the doorway and begged him to stop. And one of Armando’s small sons, Anthony, tried to intervene. So Armando rounded on him and beat him as well.

It happened regularly.

The boy — Anthony Lucidonio — grew up and became “Tony Luke” when he started selling sandwiches to blue-collar workingmen across South Philadelphia. He started small in the 1970s, selling from a truck, slaving over a grill to build an empire one roll at a time.

He never, ever beat his son, Tony Jr. — he absorbed that blow and never passed it down. But he did hold on to some of his father’s hardness.

“He never physically abused us,” Tony Jr. says. “But the mental abuse. The verbal abuse. Yeah.” (Tony Sr. didn’t return calls from Philadelphia.)

Tony Jr. was a fat kid, with a 40-inch waistline before he finished puberty. “You know your problem?” he remembers his father saying. “You’re the kid who can’t put down a sandwich.”

The harder the father came down, the more deeply the son lost himself in food. “It was my escape,” he says.

Once the cycle started, life had a way of perpetuating it. There was a girl, for instance, who would walk past the Lucidonio house each afternoon after school. Tony Jr. made sure to be sitting on the stoop each day as she passed by, and slowly — agonizingly slowly — they developed a small, tender relationship of hellos and smiles and gestures. One day when he was 12, he summoned the courage to write her a note with two questions, in the eternal adolescent form:

Do you like me? …… yes/no.

Would you go out with me? …… yes/no.

He passed her the note as she walked by, and she smiled as she accepted it. He watched her carry it to the street corner, where she met two girlfriends and opened it in their presence. She showed it to them. They giggled, looked at him, and then whispered something among themselves. Then she came back to the stoop. She wore a smile so sweet, and which bore so deeply into the boy’s brain, that decades of time would do nothing to blunt it.

“I would go out with you,” she said. She reached up to hand back the unfolded note. “But my friends say it’s best if I don’t talk with a pig.”

It’s the sort of moment that crushes boys into powdered saline and testosterone, and from that material shapes the men they will become.

He took the note from her and ran inside, where his grandmother stopped him. “Why are you crying?” she asked.

He told her.

“Go sit on the sofa,” she told him. “I’ll bring you something to eat.”

He did. And she did. A big tray of old-world food, to console his broken heart. He sat and watched Happy Days, an episode in which Fonzie confronts Rocky Baruffi, a Falcons gang member. A tough Italian guy in a black jacket.

“See him?” his aunt said. “Whenever you feel afraid, I want you to pretend to be him.” Rocky Baruffi.

He took the advice to heart, and for months he used that living room, catered by his grandmother, to become Rocky Baruffi. The walk, the talk, the jacket. And at the end of his understudy, he realized he knew what he wanted: to act. To perform.

One day he told his father that. He had always loved to sing, too. The father stared.

“What, are you gonna wear a tutu?” Tony Jr. says his father asked. “What are you, a faggot?”

Adolescence is a time of life when the world comes in close anyway, and it was landing blow after blow on Tony Jr.: a chubby kid in South Philly who wanted to maybe try theater.

The other kids were merciless. “Fat Tony,” they would call. “Hey, Torpedo Tits.”

Then one day, when he was 13, the world brought him what seemed to be a gift.

A friend knew he wanted to lose weight and offered him some sort of small rock. “Just try it, it’s good,” the kid said.

“What is it?” Tony asked.

“It’s called crystal meth.” You inject it, the friend said. With a needle.

Tony Jr. winced. “Nah,” he said.

“Look,” the kid said. He popped the top off a 7Up bottle, and inside the fluted metal lid, he crushed the small rock into powder. Then he poured a tiny bit of 7Up into it. “Drink this.”

Tony Jr. did. And nothing happened, at first. But later, as he walked home, he felt something unfold in him. Confidence. Swagger. By the time he got home, he no longer needed to play the role of Rocky Baruffi; he had become him.

The years that followed were a blur of achievement and speed, with no apparent cost. Everything he undertook, he did explosively: He started working out, lifting weights. In just a few months he dropped from 220 pounds to 160 and had traded his fat for muscle.

When he heard about the opening of a new school in the city — the High School for the Creative and Performing Arts — he pulled on his Baruffi-style black leather jacket and auditioned. He stood on the stage and sang. He leaped down off the stage and went on all fours, pretending to be a dog, and sniffed the teacher who would select students. And out of thousands of kids hoping to get in, he won a spot. The old, fat, virginal Tony Jr. would never have had the confidence.

He used his newly chiseled jaw to talk with girls, and then to sleep with them. Many of them. Some guys in the neighborhood paid girls for sex, but teenage Tony Jr. had no need — in fact, he started organizing the girls, collecting money for them, sleeping with them for free, running cash from place to place for an escort service.

He felt invincible. Immune.

Cracks started to show. Like the time at a pool hall when he asked to use the bathroom and the guy behind the counter told him there wasn’t one available. Tony Jr. punched through the plate-glass door. His dad had to come and talk the police out of charging him, and use hard-won money from his food truck to cover the cost.

“What is wrong with you?”

There was one girl. A nice girl, named Franny.

She had a supernatural patience. She would tell Tony Jr., “Go ahead and get this out of your system. I’ll wait.”

In 1979, they had finally gotten serious and were on the verge of getting married. That’s when Tony Jr. overdosed.

He was 17, but his body had become a toxic cauldron of crystal meth, cocaine, Quaaludes, all washed down with Mad Dog 20/20 and Jack Daniel’s and topped off with weed laced with bug spray. He started hallucinating and wound up in the hospital.

So he did exactly what Franny told him to: He got it out of his system.

“I just kicked it,” he says now.

He never went back to drugs. Soon after, a baby arrived.

He named him Tony. The third.

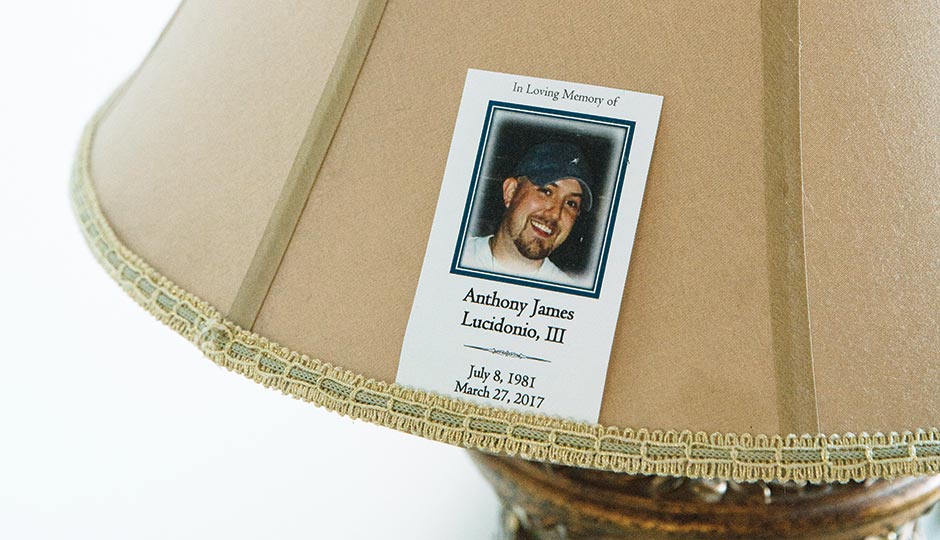

A card commemorating Tony Luke III. Photography by Gene Smirnov

Tony jr. sits on his living room sofa, waiting. Behind him stands a lamp, and into its shade he has tucked a small laminated card from his son’s funeral. A photo from the good times. Tony III was a handsome kid, like Tony Jr. had been but taller and even more muscled-up. He was a wrestler, and man, he loved to lift weights. He was a BEAST. You shoulda SEEN —

The father’s phone rings, interrupting his reverie. In a small voice he says, “Okay. I’ll be right down.”

A driver has arrived to take him to a radio station in Center City. He doesn’t want to go. He wants to lie down on the sofa and cry. But as the face of the Tony Luke’s chain of cheesesteak stores — an outgrowth of his natural gift, an ability to perform — he has obligations. On this day, that means cutting a 30-second radio spot.

At the studio, he lowers himself into a chair before a microphone and sighs. He wears another hoodie, black this time and larger, and he retreats into its folds. He looks over the script written by an advertising firm. It seems like too many words for 30 seconds, he tells the producer. But he’ll try.

The producer looks at him over the top of a computer monitor, eyebrows raised. “Ready, Tony?”

“Yeah. I guess so.”

When the mic comes on, he transforms; he sets aside the weariness and woe of Tony Luke and becomes “Tony Luke.” Becomes the brand. He seems to physically enlarge, until his face comes level with the microphone.

“Tony Luke’s prides itself on our farm-to-family promise! By serving 100 percent U.S. ground — ”

He stops, and deflates. “‘Grown.’ Sorry.” He runs a hand over his face.

“No problem,” the producer says.

Tony Jr. reinflates, rising again. “Tony Luke’s prides itself — pfffffffttt.”

He releases a stream of air, literally deflating again. “Calm down,” he whispers to himself.

“It’s too many words,” he tells the producer. He’s having to expel the language faster than his mouth can move, and it can move fast.

Again and again the producer watches as Tony Jr. blows himself up to become the Tony Luke’s Marketing Blimp, and gradually it becomes clear a heroic struggle is playing out before the microphone.

Finally Tony Jr. delivers the stream of words unbroken: Hormone- and steroid-free steak. Locally sourced vegetables. Locations from King of Prussia to the Shore.

The producer checks his monitor. “That’s 43 seconds. If we could just tighten it up a little more.”

Thirty-eight seconds. Then 36, and 32. Close enough.

Back in the car, Tony Jr. calls the ad firm. “A minute spot?” he says. He lets his shoulders slump, like a prizefighter who has given up.

“Well. It’s a 30-second spot now.”

Tony jr. always worked hard.

Not like his father, no. He was never able to match his father. But he worked hard.

He had worked alongside the elder Tony in the food truck, which became two trucks, which became a commissary where they cooked and distributed food for half of South Philly’s electricians and carpenters and pipefitters to eat.

In 1992 they opened the flagship Tony Luke’s cheesesteak shop, on Oregon Avenue near Front Street. The men in the family — the older Tony, the younger Tony and his brother Nicky — worked hard. Often more than one job.

Tony Jr.’s driving force was to move his family — Franny, Tony III, and now Michael and little Joey — to a better neighborhood. He relocated them from block to block, looking for any small improvement, but South Philly had its rough spots. At one point, some punks, he says, threw a glass bottle that nearly hit the baby in his cradle at home. And when Tony III was 10 years old, some neighborhood kids beat him, badly, as little Michael ran home to tell their mother.

“My brother and I were so different,” Michael says. He’s 32 now. “I was kind of a nerd and focused on studying. He was a jock and fought a lot. I don’t know why we were so different — I’ve thought about it a lot, and I don’t understand it.”

Tony Jr.’s black BMW glides quietly through the old neighborhood, among now-gentrifying rowhomes and churches and schools.

“That was this corner,” Tony Jr. says. The spot where Tony III took a beating for Michael. Things were different here then. The neighborhood was rough. So he moved the family again, this time to New Jersey.

“That was hard for Tony. He wanted to fit in over there,” Tony Jr. says. “And he liked a girl. And she liked pills. It was just a thing happening in Jersey at the time.”

The father only learned about that years later. “I wasn’t there,” he says. “I was gone. I was working, working. Franny had to raise the boys by herself.”

So by the time Tony III was 13, like his father before him, he was an addict.

Researchers now often say that an opioid “epidemic” has taken hold in the United States, but even that word fails to capture what is happening. In 2000, in any population of 100,000 Americans, three would die from opioid overdoses. By 2014, that number had leaped to nine, and it continues to climb. According to the Centers for Disease Control, an average of 91 Americans die every day of an opioid overdose.

The crisis has hit Philadelphia hard. By almost any other measure, life in the city has improved in this decade. Between 2010 and 2015, for instance, according to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, homicides dropped. Various accidental injuries dropped. But heroin here is both cheap and pure, and across the same years, annual overdoses from it leaped from 150 to almost 400.

Over time, Tony III fell into the familiar pattern: using pills, going to rehab, using again. He didn’t nod off in gutters or panhandle; he held together a middle-class existence. In recent years he was living in a white two-story house in New Jersey with his fiancée and their two little girls. They had a swing set in the yard. He always managed to hide his habit until some crisis — relationship trouble, a crime, a lost job — would drive him back into counseling.

For years, his father says, the son was able to gather enormous quantities of pills simply by going to the doctor. It didn’t seem so bad when he called it “medicine,” and there was always a reason. An injury, an ache.

“The car accident was the big one,” his brother Michael says.

But beneath the cycle, Michael says, his brother would show flashes of extraordinary empathy. Not long ago, Michael remembers, he and Tony III were walking to a South Philly doughnut shop for breakfast. Tony III saw a homeless man on the sidewalk, reached into his pocket, and pulled out everything he had: 20 bucks.

Michael stared. “What are you doing?” His brother had just been complaining about money.

“I don’t know,” Tony III said. “He needed it more than me.”

Michael marveled at that. Then they arrived at the doughnut shop and he had to pay for his brother’s breakfast. Those little things — flickers of humanity in a fog of irrationality — defined Tony III when he was using.

Mostly, Tony Jr. blames the doctors for fueling his son’s addiction. But he also blames what’s happened in the family.

The fracture started to form a decade ago. Business was pouring into the cheesesteak shop on Oregon Avenue,and the Lukes had settled into a division of labor that worked. Tony Sr. and Nicky handled daily operations, and Tony Jr. put his charisma and stage training to use — he filmed campy TV and radio ads that made him, and the store, locally famous.

But regional fame is better than local, and national fame is better yet. Tony Jr. came up with a plan to boost the Tony Luke’s name to new levels, which first meant bringing in a deep-pocketed investor: Ray Rastelli of South Jersey, who co-founded Rastelli Foods Group. It doesn’t have the literal sizzle of a cheesesteak joint, but RFG distributes hundreds of millions of dollars of food each year.

The plan was that each of the Lukes would do what he did best: Tony Jr., with Rastelli, would form a franchising company called TR Worldwide. The younger Tony’s profile had risen along with the national appetite for food-related shows on the Food Network, Spike and elsewhere.

Meanwhile, the franchising deal would kick back a cut of profits to Tony Sr. as the founder of the original store. And he and Nicky would keep the original, now-sprawling store on Oregon Avenue and a smaller one in Wildwood, except for a five percent stake for Tony Jr.

Rastelli sank money into the project, building more than 20 franchises around the country and amplifying Tony Jr.’s marketing voice.

It all started to fall apart three years ago, according to Tony Jr.’s lawyer, when a customer walked into the original shop and asked for a picture with “Tony Luke.”

“The father came out and said, ‘I’m Tony Luke,’” the attorney, Paul Rosen, told Philadelphia magazine last year. “And the guy says, ‘No you’re not.’ And the father went ballistic, and from that point he decided that he was going to try to compete with his son.”

That’s when the legal fight began. According to a lawsuit brought by TR Worldwide, Tony Sr. fired Tony Jr. from the store at Oregon Avenue and Front Street in July 2015, “thereby cutting off all his income.” That suit also alleged that Tony Sr. and Nicky “secretly decided to create their own hybrid brand under the name ‘Papa Luke’s.’” While that case was ultimately dismissed, Tony Sr. and Nicky have brought their own suit against TR Worldwide, alleging they were duped into signing an earlier agreement and are owed money. The fight still carries on.

For a long time, Michael maintained good relationships with both sides of the family, so he witnessed the rift up close. His assessment is simple: “My grandfather and uncle work with their hands,” he says. “To them, if you don’t physically do the work with your hands, it’s not real work. So the things my father was doing just seemed ridiculous to them.”

Gradually the cheesesteak civil war put the youngest Tony — Tony III — in an untenable position, trapped between his father on one side and his grandfather and uncle on the other.

It’s not that he minded the work of cheesesteaks. He never resented it, and he was good at it. “Tony could work like no one I’ve ever seen,” Michael says. Making and selling sandwiches usually takes several people working as a team — at a prep station, at the griddle, at the cash register and so forth. “Tony could do them all at once, alone. He just had a mind for it.”

So he made an unexpected flight, last year: He went to work at Geno’s, the legendary South Philly cheesesteak spot. There’s a rivalry among the cheesesteak empires, but it’s familial. “I would have created a job for [the youngest] Tony even if I didn’t have one,” says Geno Vento, whose late father founded their business. “Just because he’s Tony’s son.”

People came to Geno asking, “Do you think he’s here to spy on us?”

He told them: “No. Tony [Jr.] is a close friend.”

Tony Jr. and Geno, two cheesesteak scions, had known each other since they were young. Years ago, when Geno still felt awkward about being public in his sexual orientation, Tony Jr. pulled him aside one day. “Geno, just so you know,” he said. “I don’t care that you’re gay. You’re my friend, and I care about you.”

It was an affection the older generation wouldn’t have understood. It was the bond between two oddball sons trying to step out from their fathers’ shadows.

Here’s the hard part.

When Mark Wahlberg came to town to film The Happening a few years ago, the shoot featured a Tony Luke’s shop in the background. Tony III would be on-set, and he was excited about it.

“Let me come down and introduce you,” Tony Jr. told him. He had some Hollywood experience by this time and had played a rabid Eagles fan in another Wahlberg movie, Invincible. He knew the producers, he told his boy. He could get him a small part, maybe. Make some introductions.

“No, Dad,” the son said. “Don’t. I want to do this on my own.”

Tony III was in his mid-20s and hadn’t yet worked out what he wanted to do. But he wanted to do it on his own. He wanted to prove himself. “All my brother ever wanted was my dad’s approval,” Michael says now. “Even when he did something right, he’d say, ‘What does Daddy think? Is Daddy happy?’”

(That term — “Daddy” — with its adult burden of affection and fealty and submission, runs in the family. Tony Jr. still slips into it, from time to time, when talking about Tony Sr.)

As the Wahlberg movie shoot wound down, Tony Jr. visited the set one day and was shocked to see his son in line to eat cold chicken with the extras and crew. “What are ya doing?” He pulled him out of line and toward Wahlberg.

“Dad, stop. I’m not allowed.”

But the father made the introductions anyway, and the producers seemed delighted. “Ah, Tony! This is your son? Why didn’t anyone say anything?”

That day, the son didn’t eat cold chicken. “He ate next to Mark Wahlberg,” Tony Jr. says. He pauses between words, for emphasis. “Mark. Wahlberg.”

He shakes his head, then unwittingly summarizes the entire Lucidonio saga, across four generations: “I don’t know what he was thinking. I mean, I did all this work so he could do those things.”

There are elements of these men’s lives that are unique to South Philly — Italian men, hawking cheesesteaks in neighborhoods — but there’s more that’s common. It’s universal and insidious, the way sons become their fathers. They see with perfect clarity the generation that came before, and feel baffled by the one that follows. So change comes incrementally, at best:

The immigrant great-grandfather beats his son.

The first-generation father lashes his son with his tongue.

The second-generation father misunderstands and overshadows his son.

And the third-generation man, looking for escape, meets a wave of opiates that takes his life.

Tony Jr. was at Lincoln Financial Field, promoting and cooking at the Tony Luke’s counter there, when his phone rang. It was Michael.

“Dad?” he said.

Something about his voice — was he crying? — made Tony Jr. sprint away from his work and up the stairs, searching for better reception. He fell and cracked his shin against the stone step, sending his phone clattering away.

He kept moving. “Michael? What’s happening?”

“Dad. Tony’s dead.”

As he arrived out on the street, the father dropped to his knees and howled.

He went to the white two-story in New Jersey, with the swing set in the yard. Tony III had died upstairs, in the bathroom, shooting heroin. As doctors become more aware of prescription pill abuse, they’re writing fewer scripts. So people like Tony turn to something quicker and more potent. And it kills them.

“He did not kill himself. He lapsed and made a mistake,” says pastor Brian Donnachie. For a year or so, Tony III had been coming to Living Hope Worship Center in Swedesboro, New Jersey. “We knew he had some issues, but he was working away from them.”

When Tony III first came to the church, he introduced himself as Anthony. Just Anthony, he told people.

“He wanted to make his own mark,” Donnachie says. “He wanted to move out from under the family name. He was so close. But he didn’t make it.”

Photography by Gene Smirnov

At his condo, Tony Jr. stares out at the river. Philly on the left, Jersey on the right.

“None of this is mine, you know,” he says softly. “I’m bankrupt.” Not legally bankrupt, he explains, but his personal finances are in ruins: The condo is borrowed from his business partner. So is his car.

There’s a knock at the door.

It’s Geno Vento. He says he wants to see Tony Jr.’s fancy virtual-reality machine, but there’s a deeper concern etched on his face.

“Doing okay?”

“Yeah. I am.”

Another friend — René Kobeitri, a French chocolatier — comes by, too. And for the first time in days, Tony Jr. seems fully alive. Among his friends he swells in volume, trading stories, laughing. He straps them into the virtual-reality system and throws his head back, laughing, as they totter around, unbalanced.

Later, alone, his grief hardens again into rage, which he typically turns toward his father.

“He didn’t bother coming to the funeral. My son dies and he doesn’t bother to show up,” he says, pacing in his condo.

He starts reciting the eulogy Michael wrote for his brother that day:

“Over the last few years, I’ve heard a particular word used a lot to describe my brother. That word was ‘weak.’ I’m here to tell you he was not, not by any stretch of the definition. My brother was a very troubled soul, and he carried with him a disease and a demon that no one should have to carry. … It was a constant struggle.”

Maybe Tony Sr. was there — had slipped in the back at the funeral, when no one was looking?

“He fucking wasn’t!” Tony Jr. shouts.

How could he know?

The 55-year-old son’s throat tightens as he approaches the heart of the pain: “I know he wasn’t at the funeral because I was looking back for him the whole time.”

Published as “Unto the Sons” in the July 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine.