I See “The World” Differently Than Ta-Nehisi Coates

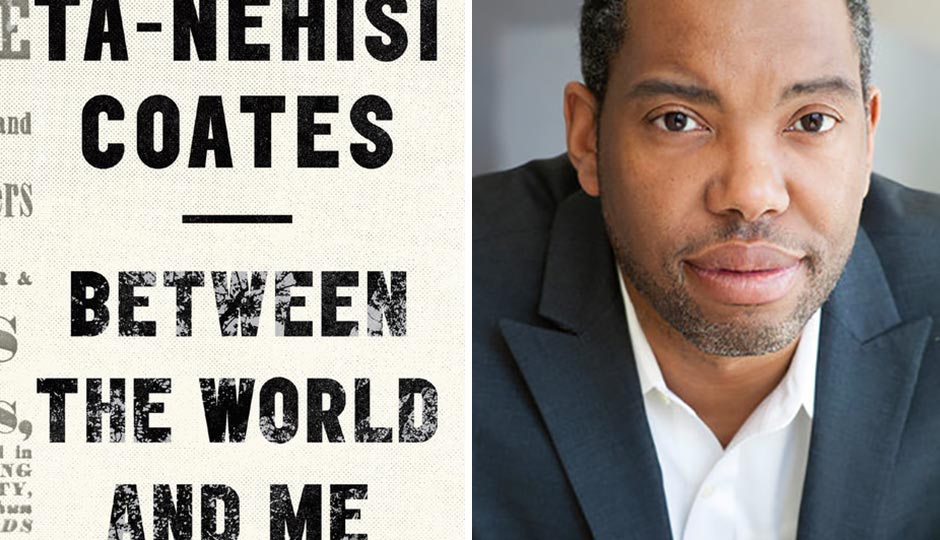

Coates | Nina Subin, Penguin Random House

I missed out on the hottest ticket in town when Ta-Nehisi Coates was in Philly in October for a talk at the Free Library based on his bestselling, National Book Award-nominated tome, Between the World and Me. (There is a streaming finalists reading tonight at 7; the awards will be announced tomorrow.)

Chances are, though, that if you are an avid consumer of ideas, you’re talking about him anyway, even if you missed the talk, haven’t read the book or one of its many excerpts, or missed his chat with Terry Gross on WHYY’s Fresh Air.

That’s because Coates has undeniably struck a national nerve at just the right moment. As the drumbeat of stories in which cops kill black men (and they are mostly men) with questionable use of force continues, along comes Coates to tell us this sort of thing is encoded in our nation’s DNA.

Like James Baldwin before him, Coates has cast himself as our racial Cassandra, reminding us that the debt for slavery remains unpaid and condemning society for failing to recognize this. And like Baldwin before him, Coates has decided that it’s best to reflect on his native land’s transgressions from afar — Paris, to which numerous African-Americans fed up with the United States have retreated.

You know Paris. That’s the capital of France, the country against which the enslaved Haitians successfully rebelled in 1804, which had its own African problem in Algeria and where the National Front today stokes fears of a dark, if not necessarily black, nation taking over — fears that have been raised to new heights by the recent ISIS attacks on Paris.

Dig just a few feet beneath the surface of every human civilization and you’re likely to find some atrocity, some sin against its own and its own professed ideals. Too many of us ignore this fact in judging societies, and it’s quite understandable that African-Americans would not care as much about those instances when those committed against them continue to sting so sharply.

Were I raised in downtrodden West Baltimore in the post-Civil Rights era, or on the gang-plagued, Rizzo-ridden streets of 1970s Philadelphia, I might also experience America the way Coates does. And I do recognize this land in many of the perceptive essays he has written, none more than “The Case for Reparations,” his systematic explanation of how blacks were kept off of the great escalator of upward mobility by racist housing policy for most of the last century.

And yet, knowing all this, I still don’t see the same country — or the same bleak, hopeless future — he does.

I attribute some of this to that different upbringing. That pervasive fear and mistrust of the police that soaked into the souls of those West Baltimore families, if it was present in the Kansas City of my youth, was expressed in very muted form at worst. Black Missourians, though reminded that they were still Less Than in many ways, may have sat in the back of the electoral bus, but they were allowed on board; Boss Tom Pendergast courted “the Negro vote” as assiduously as he did all the others. The white folks’ departure from my old neighborhood was slow and gradual, not sudden.

In short, it was a world that would have seemed to Coates as foreign as the white-picket-fence suburbs depicted on TV. And it produced a black community that at once knew the sins of white society yet still sought to enlist it in atonement. (Pardon me for using the language of religion here, for that is also alien to Coates.)

It’s a world closer to the one that produced my near contemporary Barack Obama — whose mother, by the way, was a Kansan, like my own. So maybe it ought not be a surprise that I cannot buy at retail the total indictment of the society that produced both Coates and me.

The President and I both learned the power of hope (and faith) as a force that allows an oppressed people to not only endure, but overcome. That we are now engaged in a searching conversation triggered by both the experience of an Obama Presidency and Coates’ fusillade at the society that made him President demonstrates that we indeed have yet to and may never achieve that hoped-for full redemption/atonement/synthesis/revolution, but it also shows that, contrary to what Coates appears to feel in his bones, the last century of struggle was not for naught.

For the white reader picking it up in the post-Ferguson era, Between the World and Me is a slap in the face, a revelation that leads even critics like David Brooks to wonder whether criticism is the right response. A black reader, on the other hand, brings some knowledge of the territory to the reading and can thus respond with more nuance. Many of us, exposed to that “softer” side of American prejudice, have come to the conclusion that better can and still must come.

I hope that the distance of an ocean and the cushion of a MacArthur Fellowship may give Coates a chance to see and understand, if not appreciate, the virtues that lie in that “softness” — and maybe even the ability to understand a different sort of struggle.

Follow @MarketStEl on Twitter.