Straight Outta Compton Sucks, And Here’s Why

You don’t need me to write out the lyrics between the line breaks. And you probably don’t need me to write out the tales of their misdeeds—from assault accusations to bigotry to XXX 2. No, the Internet is swarming with heavy-handed think-pieces on the place of NWA in a #BlackLivesMatter world—as it should be. It’s a matter worth discussing, the effect of the one of the most profitable, aggressive hip-hop groups on the state of black America.

Let’s just talk about the shitty movie they made.

The only character the viewer feels closer to after seeing Straight Outta Compton is Eazy-E, with whom the director and producers (NWA survivors Dre and Cube) feel exclusively willing to fuck around with, because he’s dead and therefore can’t personally object to his on-screen portrayal. The film is largely an exploration of the rise and fall of Eazy as paralleled by the meteoric careers/sell outs of his teammates. In one of the only instances of character development, we see Eazy coached by Dre as he sheepishly tries to throw down the opening line of Boyz n the Hood, only to be bolstered by proper encouragement by the brotherly Doc, framing the warped reality that the movie wants us to believe.

Paul Giamatti as James Heller in Straight Outta Compton.

Eazy—portrayed exceptionally by Jason Mitchell, who throws everything he can in to becoming the lauded-then-abandoned kid genius that Eric Wright was—falls under the spell of infamous-ish manager Jerry Heller, portrayed by Paul Giamatti, who wears the second-worst wig of the 2015 summer movie season. Heller is only portrayed as Svengali in the last thirty minutes of the picture when, out of nowhere, Eazy’s wife discovers that Heller’s been withholding funds—or something—and is later confronted by Eazy in a fight that involves (a) a bizarre line repetition and (b) a string of impersonal pronouns deployed so that the viewer can’t really figure out what they’re fighting about, because the movie forgets to set that up earlier.

Eazy E is a complicated dude and Mitchell gets way under him giving him a joie de vivre, a mean streak, and a crisis of identity or two. His story, however, is flanked by those of Cube and Dre. And those stories, as presented by executive producers Cube and Dre and their faithful border collie director F. Gary Gray, are as boring as they are toothless.

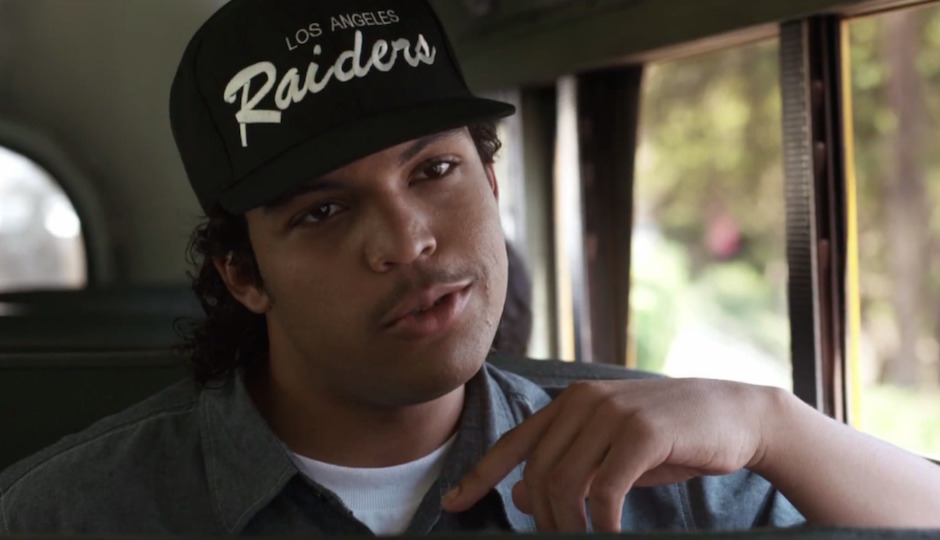

O’Shea Jackson Jr. as Ice Cube

Ice Cube is portrayed exactly how Ice Cube would want himself to be portrayed; his character never shows a glint of self doubt or internal struggle. Instead he touches on every iteration of himself that Cube has presented to the media. He is, at first, a kid with big dreams. Later, we see him hammering out the script for Friday in his blissful family room. In between, we get concert scenes that show him to be the baddest motherfucker on the planet, a committed and clever political firebrand and, in a scene in which he destroys a record label executive’s office with a baseball bat, the kind of anti-authority, risk-taking goon he pretends to be in his raps. Naturally, there is no explanation for these floating personality phases. If the movie is to be believed, this quintet of avatars truly compose the corporeal Ice Cube.

Dre gets a more even, sympathetic turn. Corey Hawkins, who plays the good Doctor, gives us a stoic, shrewd, heroic Doctor Dre, one who is deeply affected by the death of his younger brother. The news of said death is delivered to us in one of the only artful scenes in the film, wherein NWA et al. crowd around a grieving Dre as the camera pulls back on their embrace. Toward the end of the film, Dre heartfully acquiesces to Eazy’s request to get the band back together, knowing his friend is in dire straits. One of the film’s concluding scenes shows Dre standing up to the comically demonic Suge Knight. Hell, even Dr. Dre’s drunken real life high-speed chase is portrayed as a reaction to the excess and madness of Suge and his entourage. Gone is anything that would make Dre a compelling character: his perfectionism, his known cruelty and abuse, and the time he spent working on The Chronic are all jettisoned in favor of creating a streamlined, winsome movie hero.

None of this is too shocking. Music biopics rarely give us a cold-hearted take on their subjects. But under the meandering direction of Gray, Compton feels like mid-budget hip-hop propaganda that tries to show the primaries as not only political reactionaries, but well-intentioned chosen ones.

The movie ends with a montage of the achievements of Dre, Cube, and Eazy, consisting of Dre’s Beats commercial, Cube’s movies, and Eazy mugging. Never mind the careers of DJ Yella and MC Ren, NWA members. Ren may as well never have existed, per Compton, and Yella’s complicated post-NWA life (read: making a zillion dollars in porno) was too difficult to sanitize for him to be in the movie for too long.

Outside the portrayals of the characters themselves, there are glaring weaknesses in Straight Outta Compton’s composition. Gray’s concert venues all look the same; the settings, colorless and bleak—regardless of scene—are unengaging, nods to famous NWA lyrics and group lore are hamfisted. But these aren’t the reasons for the sum failure of the film. Compton fails because we don’t really find out who NWA are, how fame changed them, or why we should care if it turned out perfectly for everyone but poor Eazy.

There’s so much to say about the sociological underpinnings of the film, and it seems that everyone who has seen it has tried their damndest to unpack it. The painful impression that it left me with, more than any other, is that the authority will do anything it can to portray itself in a positive light.

Cops will lie about how cases are handled, even though body camera footage will prove them wrong.

Politicians will shift the weight of legislative failures to easy-bake issues like immigration.

And even NWA—at once the harbingers of a grimacing era of social discontent—with their billions of dollars and their #brands to take care of, will make a movie that claims without even a smirk that they’re the good guys and always have been.