Why Are Philadelphia’s Streets So Filthy?

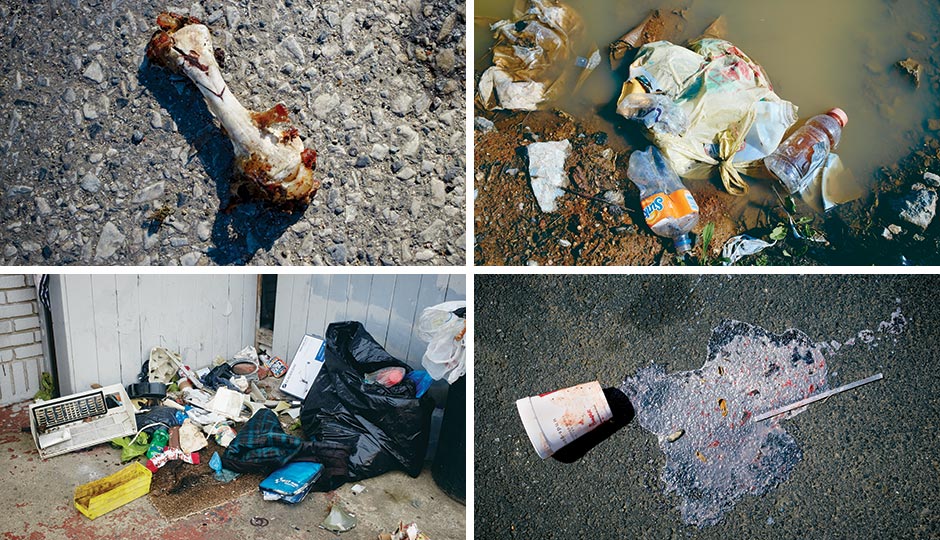

Photography by Mark Likosky

Every snowy week this past winter, my block in Bella Vista resembled the site of a garbage strike. Lumpy piles of trash built up day after day, knocking over brown-paper recycling bags that dissolved into mounds of cardboard-and-plastic-bottle mash, hair weaves and food wrappers. It looked like the prequel to Wall-E.

Of course, it wasn’t just my street — nearly anyone in the city could describe a similar scene. That’s just what you see in Philadelphia in wintertime. Oh, and also on windy spring days. Or fall ones. And also, sometimes, in the sweltering still of summer. Garbage in the street, on your stoop, swirling into your eyes. That’s life in Filthadelphia for you. And that’s not just Philly cynicism talking: A few years back, when Travel & Leisure ranked the dirtiest cities in America, Philly was runner-up only to New Orleans. And in May, City Controller Alan Butkovitz released a report noting that some 80,000 households in Philly don’t have their trash collected on time in any given week.

All of this is why I found myself riding shotgun inside a 20-cubic-yard high-density compactor one dewy spring morning, traversing Southwest Philadelphia. I wanted to get a firsthand look at Philly’s foul front lines and figured a morning with longtime driver Rondell Bentley was the place to start. Bentley, a likeable middle-aged guy with salt-and-pepper stubble, has seen a lot of shit in the 15 years he’s spent working for the Streets Department in sanitation. Literally, shit, as in entire Hefty bags of human waste. Although that’s nothing compared to the photo he keeps on his iPhone featuring a pair of white fangs sandwiched between a Hi-C juice box and a Save-A-Lot bag — fangs belonging to a decomposing, full-grown American bulldog.

Anyway. Bentley is part of a team of 240 crews out daily, each of which hits about 1,000 homes in this city, collectively gathering up some 675,000 tons of trash and recycling annually. He told me the route we were on is one of the cleaner, better ones, notwithstanding the scattered construction rubble abandoned curbside, or the blonde who opens her door to lob a grenade of mutilated plastic bags directly at the men while flinging obscenities I can’t repeat on this page.

Bentley is unperturbed by any of it. He’s grown used to a lot of this — the hostile attitudes of residents, the putridness a trash bag takes on when it’s left open in the sun or when mystery liquids leak through, the garbage scavengers who knock over bags, spreading refuse around the block. The same can’t be said of most Philadelphians, though. In fact, a 2009 Pew survey revealed that dirty streets came in second only to violent criminals on a list of things Philadelphians dislike most. We hate our grime more than we hate taxes, bad schools, crony politicians or the Parking Authority.

It’s hard to ascertain exactly how much filth we’re talking about. Outside of litter citations (30,171 last year), there aren’t a lot of refuse metrics out there — mostly just anecdotes. So many anecdotes. There’s the friend in Fairmount who rolls her baby stroller over used condoms plastered to the sidewalk in front of half-million-dollar houses. A colleague in South Philly who required cortisone shots in her wrist from sweeping up the garbage strewn all over her block. An out-of-town guest who comments on the detritus that jumps out at him as a primary feature of the city.

Our trash problem has become an accepted part of daily life. But when you stop and see your city through that out-of-town guest’s eyes, it makes you wonder how, exactly, we got here. It’s also tough not to think about all the other guests this city will welcome in a matter of months, with visits from the Pope and the DNC. Will they, too, see garbage as our standout feature? Can we ever scrub ourselves clean of the filth that’s become our status quo?

Or do we really even care anymore?

The photographs in this feature were all taken on a single Saturday in April by photographer Mark Likosky as he roamed the city streets from dawn until dusk.

WHEN THE SUBJECT OF TRASH in the streets comes up, Philadelphians often point at the sanitation workers — men and women like Bentley — as major culprits.

“Our trash people care as much as everyone else, which doesn’t help,” offers my friend Kate, who lives in South Philly. One recent Facebook screed from a Point Breezer just raged: “God forbid they work an extra day on a salary that pays them $47 an hour or more!” And on Reddit: “Trash day in Philadelphia means the day that the trash men come by whatever time is most convenient for them, pick up maybe 80 percent of the trash in front of your house, and redistribute the rest of it on your sidewalks and down your street.”

Harsh words, but there’s some truth there. On the route with Bentley, I saw how hard the trash crew worked, hauling away couches and crutches and sheetrock without complaint. But I also saw trash get dropped. I saw the crew take time to flirt and smoke. I saw that the group didn’t double back to pick up lost trash, saw Wawa wrappers spiraling like ginkgo leaves from collection bins. And when it comes to the inconsistency charges, the Streets Department admits the crews collect 30 percent less garbage the day after a snowstorm (which seems generous). According to Butkovitz’s report, on-time trash collection rates have dropped from 96 percent in 2013-’14 to 85 percent in 2014-’15. (“On-time” is anytime before 3 p.m. on pickup day.)

So what gives? In a word, money. We’ve been feeling the effects of massive cuts from the department that handles our trash. In 1990, the Streets Department ran on more than $275 million; in 2000, about $158 million (both in 2015 dollars). Today, it’s operating on $118 million. That’s a 26 percent drop from just 15 years ago. Meantime, the city has grown by some 9,000 residents.

“People are now forgetting that this administration went through the greatest recession since the Great Depression,” says Streets Commissioner David Perri. “We were going through Sophie’s Choice budgeting during those days.” You remember: Mayor Nutter was talking about shuttering public libraries and rec centers, laying off 3,000 city employees, moving trash pickup to every other week. And while the city didn’t end up coming close to all the doomsday scenarios, the recession did end regular residential street-cleaning and swallow up the capital funds reserved for truck upgrades — the same trucks that double as our snow-removal vehicles.

Over these past two winters, those chickens have come home to roost. “Whatever life was left in these vehicles, [the bad weather] just knocked the hell out of them,” Perri says. The down rate of trucks — in the shop or out of commission — has risen to as high as 35 percent. The broken trucks only compounded the effects of five snow-cancelled collection days this past year. The Streets Department will get 30 new trucks this summer, but truth is, it’s been begging for reinforcements for years. Those new trucks won’t even bring the fleet up to capacity.

It must be hard to operate under such constraints, I say to Perri. He says that even as his truck situation grew increasingly dire, the fire department needed new ladder trucks, and the city’s medic units were hurting. “Would you rather be talking to the fire commissioner today about how someone dies because they couldn’t get up a ladder?” he asks. “Or would you rather be talking to me about why somebody was inconvenienced because we couldn’t pick up their trash?”

Perri would love to make something like, say, curbside compost collection a reality, but even his wildest dreams don’t fly that high. So what would he do with a sudden windfall? He’d add twice-a-week pickups in the most densely populated areas, he says, and employ more people to track down illegal dumpers — residents who leave giant piles of trash in public bins, and construction businesses that dump wreckage in dingy or abandoned areas. He’d also restore residential street cleaning.

“I’ve never been to a place where the city didn’t pay people to sweep the streets, either mechanically or by hand or both,” says Jim Resta, a former urban planner in the Delaware Valley who moved to San Francisco earlier this year. San Fran has regular street sweeping. So does snowy Minneapolis. Hoboken, too. Detroit, for Pete’s sake. These cities got hit by the same recession as Philly. And yet, we are the only major U.S. city without a comprehensive program. (In select commercial corridors, the city still sweeps sometimes.)

To save money and keep their garbage in check, other cities have experimented with everything from privatization of trash collection (Toronto) to pay-as-you-throw programs (Austin). As far back as 1981, New York switched from three-man sanitation crews (which is what Philly uses) to mostly two-man crews. Collection rates remained about the same, and the city saved $38 million a year.

It seems a little insane, as Perri points out, to fret over dirty sidewalks when our schools and roads and, yes, fire trucks are falling apart. But it’s also hard not to wonder if our dirty streets are the result not just of funding failures, but also of a failure of imagination.

AS YOU STROLL THROUGH Center City, it’s possible you never spot a single bag of dog poop, rogue chicken wing, or ketchup packet stuffed in a tree trunk. That’s because the teal-jacketed army of litter-pickers and sidewalk sweepers working for the Center City District get to them first.

When the CCD formed in 1990, the streets of downtown Philly looked like a lot of outlying neighborhoods today. “There was a clear recognition that government couldn’t do everything,” says Paul Levy, the CEO of the CCD. Levy convinced business owners it was in their best interest to pay a fee for the maintenance of clean, safe sidewalks. Immediately, everyone saw a difference. The cleanup, Levy says, was contagious: The tidier CCD kept the sidewalks, the less litter was thrown down. “There was this incredible psychological boost,” he says.

Levy’s model and its success have been replicated elsewhere in the city — by the University City District and the Passyunk Avenue Revitalization Corporation (PARC), to name two examples. PARC eschews fees, and instead pays for cleaning through the income it makes by leasing out rehabbed properties. In both cases, residents aren’t paying for these special services. “The system works relatively well in commercial areas,” Levy says. But given the high concentration of residential neighborhoods in the city, it’s hardly a magic bullet, he admits.

A different prescription, he thinks, might be something incredibly basic: more trash cans. “Well-meaning people who walk four blocks with a sticky wrapper at some point lose their patience,” Levy says. City Councilwoman Blondell Reynolds Brown agrees. In May, Council passed a bill she introduced requiring any business selling food to provide trash and recycling receptacles within 10 feet of the entrance. It seems a painfully obvious first step, but the Streets Department has long been wary of such a move. It’s not just the added burden on trucks and men; for them, more trash cans mean more illegal “short dumping” in (and around) trash cans that aren’t designed to hold residential trash — inviting more litter to pile up and blow around.

The short dumping is a problem not lost on the Councilwoman, who also proposed — and passed — a second bill aimed at curbing some of the illegal dumping by requiring landlords of buildings with 10 or more units to provide dumpsters for tenants who otherwise would have nowhere to empty their overflowing waste bins between trash days.

To the city residents who have for years been bemoaning a lack of convenient waste bins, such bills are welcome (if overdue) steps in the right direction. Some neighborhood activists took up the trash-can mantle long before any Council bills. In 2010, the South of South Neighborhood Association (SOSNA) proposed and coordinated a plan with the Streets Department for trash pickup. Streets agreed to service any BigBelly solar trash compactors the neighborhood purchased. SOSNA has since raised enough money via advertising and donations to buy six cans.

At $4,500 a pop, even one BigBelly is no small investment. The city spent a jaw-dropping $2.2 million on 500 of them in 2012, but it was a victory for an administration aiming to green the city: By compressing trash automatically, the cans reduce pickups to three to five times a week, compared to 17 for wire baskets. (Many BigBellies have a separate hole for recyclables.) They save wear and tear on the trucks, save fuel costs, lower our carbon footprint (slightly), and — most impressively — save the city some $1 million a year.

But unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past three years, you know that even these magic bins, still mostly located in Center City, have their detractors. “I never want to touch the handles because they’re usually sticky or grimy,” says my friend Samantha, who lives in Bella Vista. It’s true. Set yourself up near a can and watch: Some people use tissues to open the trash door; some grimace and pull it open with their fingertips; once in a while you see someone hoist a leg three feet in the air to pull the door with a foot. Some just throw trash on the ground. Samantha has her own method: “Most of the time, I just toss my garbage in the recycling hole.”

IT’S A GORGEOUS SPRING MORNING in Germantown’s Vernon Park on the day of the eighth annual Philly Spring Cleanup. More than 14,000 volunteers are kicking off 723 beautification projects throughout the city. Mayor Michael Nutter takes the podium, slips into an XXL tee, and launches into a pep talk. (“It takes a team to keep it clean!” he says. And: “Over one million pounds of trash will be cleaned up today!”)

Later, I ask the Mayor why he thinks there’s so damn much litter to pick up. “When I was a kid, people didn’t have to tell us to come out and clean your block,” he says. “It’s your block where you live! It’s your outdoor living room! Take care of it.”

The Mayor has gotten some heat over the years for an attitude some interpret as “nanny politicking,” but to me, what he said seemed more direct and authentic than the city’s official stance on littering: the UnLitter Us campaign, which launched in 2010 and featured spoken-word poets as the voices for anti-littering.

“I think I have more Twitter followers than UnLitter Us,” says Emaleigh Doley, a trash activist and block captain in Germantown. (She’s right: Doley, 2,455; UnLitter Us, 1,749.) “It’s a PSA publicity campaign and shouldn’t be treated as a litter initiative.” The citywide program does issue certificates for litter-free school zones (13 so far) and blocks (504) — but the awards are little more than decorative signage. A few years ago, Doley received an aluminum street sign for having a “litter-free block” — the result of tirelessly organized neighborhood cleanups — and was bummed when there was no follow-up from UnLitter Us, no supplemental resources, no tiered reward system for expanding cleanliness efforts.

The program is run by an advertising agency, LevLane, whose national clients include KFC and Taco Bell. The Streets Department foots the bill for LevLane’s media campaign — $140,000 this past year out of a total annual cost for the entire program, including clean-up efforts, of $500,000; the rest comes from the city’s general fund and a state grant. Perri thinks outreach and education are important in keeping the city clean, but like Doley, he’s no fan of UnLitter Us. “Too highbrow,” he says. Anyway, a hundred thou and change could buy (and clean?) an awful lot of BigBellies. Or serve as a down payment on strategic street sweeping. (Regular citywide street sweeping would run $3 million to $4 million a year.) Or even go toward littering-code enforcement, another rough patch in Philly’s trashscape.

“I don’t know of anybody who ever got a littering ticket,” says Councilman Mark Squilla. “People say ‘Create laws.’ Well, we have laws; we just need to enforce them.” (In April, Squilla actually proposed legislation requiring businesses to charge five cents per plastic or paper bag to customers who don’t provide their own.)

But enforcement is another hurdle. Right now, the city’s primary litter-code enforcement is the Streets and Walkways Education and Enforcement Program (SWEEP), civilian officers who issue various citations for transgressions that range from illegal dumping to littered sidewalks. There’s also a special unit of the police department devoted to illegal commercial dumping; it rotates 20 cameras around the city’s most notorious dumping zones. But SWEEP employs just 53 officers in a city of 1.5 million people. Even the violators who are caught and fined apparently don’t all pay. The Streets Department issued some 30,000 litter violations in 2014. Your run-of-the-mill littering fine is $100, but the city brought in just $579,000 — or about $19 per citation.

It’s not quite the deterrent former streets commissioner Pete Hoskins envisioned when he helped found SWEEP in the early ’90s. “In a lot of other cities, people accept the idea that if you do something like dumping or littering, you’re going to have a consequence,” Hoskins says. “In Philly, not really.”

TWENTY-TWO GLOVES. Two gallon jugs of antifreeze. Two raccoon skulls. One Michael Vick jersey. A Ziploc bag full of wallet-sized pictures of a baby goat. Three pregnancy tests. (For the record: one positive, one negative, one inconclusive.)

These are just a few of the 3,768 pieces of garbage that 38-year-old Brad Maule picked up on weekly hikes through Wissahickon Park over the course of one year. Maule, the co-editor of urban preservation-and-planning website Hidden City, started picking up trash in the park just because it bothered him, but then decided to turn his haul into an art installation. One Man’s Trash debuted at the Water Works in late April as an awe-inspiring reminder of personal wastefulness. “I’m from the country, and the ‘leave no trace’ principle was something we learned about at a young age,” Maule says. “Around here, it doesn’t seem to be as widely known.”

In 2009, Maule had been living in Fishtown for two and a half years when he got fed up with the filth. “It was the little day-to-day stuff that wore on me — real, tangible things,” he says. Dog shit. Broken glass. Endless Arctic Splash iced-tea cartons. He packed up and left — moved to Portland, where he says he saw an almost Zen-like respect for the environment percolating throughout the culture, from mandatory recycling to compost collection.

When Maule came back to Philly four years later, much had changed — especially in Fishtown. There were new parks. New businesses. A new vibe. New homes, new families, new Philadelphians. But there was the same trash. Right down to the Arctic Splash cartons in the gutters of the streets.

It hits me: That’s the real rub with our trash issue. So much of the city is progressing, and at lightning speed. We’ve got the Pope, the DNC, the bike lanes, the parks, the recycling collection that’s nearly tripled over the past eight years, the Office of Sustainability, the beer gardens and the Delaware waterfront, and on, and on — Philly is moving forward in so many exciting ways. But we’re still mired — literally — in garbage. It doesn’t fit. Filthadelphia is antithetical to the Philadelphia of 2015. Tumbleweaves are so 10 years ago.

But you know, I think that realization is actually starting to dawn on us — and not just on the Emaleigh Doleys and Paul Levys and Brad Maules among us. I think that’s what’s behind all the criticism I heard about garbagemen, all the public shaming of litterers you see on Facebook and Tumblr, all the people griping about services we don’t have. I think it’s a sign of a collective sea change away from tolerance and acceptance of garbage that’s beginning to take hold. Perri thinks so, too. “The attitudes are changing for the better,” he tells me. “People are demanding increased performance from city departments and also putting in their own elbow grease.” All the angst, Perri argues, isn’t a memento of this city’s intractable problem, but rather a glimpse into our next chapter. “The argument of whether Philadelphia can become a World Class City is over!” he wrote to me.

For now, though, the trash seems like the most visible barrier between what we can be and what we still are. Perri shows me a photo — one of his favorites, he says, soon to be mounted in his office. It’s a wire basket bloated with garbage stacked well past the brim and sitting on a swath of Philly sidewalk next to a soiled toilet, which is also overflowing with boxes, bottles and cans.

“I say, look, there’s a glimmer of hope here at least,” Perri says with a wry smile. “People are putting their trash inside the tank and not on the grass.”

Five Garbage Ideas Philly Should Steal

From a pay-as-you-throw policy to privatized collection, here are smart ways other places manage their trash.

1. Pay as You Throw

Who does it: Austin, San Jose, Doylestown

The draw: Think of PAYT as garbage collection transformed into a utility — the more you place curbside, the more you pay. (Your neighbor might think twice about leaving that broken-down armoire on the sidewalk, eh?) Residents are required to buy special trash bags, and trucks measure their weight upon deposit; this generates a unit-priced charge. Recycling isn’t metered. Thus, PAYT raises money and incentivizes responsible behavior — and it’s led to reductions ranging from 20 to 60 percent in solid waste in municipalities that use it.

The Philly challenge: When Nutter proposed a trash tax a few years back, Council unceremoniously squashed it. PAYT would undoubtedly face the same hurdle.

2. The 30-Pace Plan

Who does it: Disneyland, Disneyworld

The draw: When, back in the 1950s, Walt Disney observed patrons dropping their hot-dog wrappers on the ground in other theme parks, he counted to see how far they walked with trash in their hands before they dropped it. The answer? Thirty paces. Now, at his parks, you’re never more than 30 steps away from a bin. As it happens, City Council recently took a cue from the happiest place on Earth, passing a bill requiring stores selling food to have trash and recycling bins within 10 feet of their entrances. It’s not every 30 paces, but it’s a start.

The Philly challenge: The Streets Department warns that more cans might mean more illegal short-term dumpers, which leads to overflowing cans and more trash in the streets. Time will tell.

3. Privatized Residential Trash Collection

Who does it: Detroit, Chicago, Toronto

The draw: Competition naturally reduces the price tag when cities put out bids for private haulers — one industry report cited savings of as much as 20 to 40 percent. Toronto saved more than $10 million a year by privatizing half its city collection; Chicago reduced recycling costs by $3 million through privatization; Detroit is projected to save $6 million after fully privatizing last year.

The Philly challenge: Hello, unions.

4. Automated Trash Pickup

Who does it: Charlotte, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Pottstown

The draw: Instead of flimsy cylindrical bins, residents are issued large trash cans with flip-top lids. (So long, rodent trouble!) No more trashmen tossing bags through the air; a mechanical arm extends from a truck to scoop up the can instead. (Fewer spills!) Of all the solutions, this one seems the most wildly extravagant (and least likely to ever happen), as the initial expenditure would be something like $200 million — though it would save money long-term by cutting down on personnel and workers’ comp claims.

The Philly challenge: Aside from the piles of cash? Narrow streets mean some trucks would still need human crews.

5. Even Smarter Waste Bins

Who does it: Toronto, Cleveland

The draw: The cool technology and eco-focus of our BigBelly cans is basically cutting-edge, but the dirt and grime and God-knows-what that coats the handles can be a deterrent to actually using them. Toronto’s answer? Push-pedal bins. In Cleveland, residents have chip-encoded recycling bins that let the city track how often they’re left curbside. If you skip more than a few weeks and the city finds you’re dumping recyclables in your trash instead, they can fine you up to $100.

The Philly challenge: Foot pedals seem a way easier sell to Philadelphians than Big Brother in your recycling bin, no matter how good the cause.

Originally published as “The (Rotten, Littered, Stinking, Stagnant, Filthy, Disgusting) Streets of Philadelphia” in the June 2015 issue of Philadelphia magazine.