Can Disneyland Help Clean Up “Filthadelphia”?

Ever since Disneyland opened 60 years ago, cleanliness has been a virtue. Walt Disney designed the park so that visitors have trash cans at every turn — you’re never more than 30 steps away from a bin — and the impeccable maintenance of the sanitized grounds are part of why Disneyland attendance continues to climb upwards, even after a multi-year recession and a measles outbreak last winter.

Last week, when Councilwoman Blondell Reynolds Brown introduced legislation aimed at reducing litter in the city, she invoked the so-called “Disneyland Theory” as inspiration. The theory says that it takes the average park-goer about 30 steps before they toss trash on the ground (hence the park’s trash cans every 30 or fewer paces). Brown’s bill would require any purveyor of food to have trash cans and recycling bins within 10 feet of their business.

But is the Disneyland Theory legit? Can it really help clean up “Filthadelphia?”

Legend has it that the Disneyland Theory was not compiled by statisticians or scientists, but by Walt Disney himself. Disney observed park-goers wolfing down hotdogs in other theme parks and then littering their wrappers. He determined that it took them roughly 30 steps before they littered in the absence of a trash can.

Hygiene is never that simple, though. Yes, the park remains creepy clean. But there are also more than 600 people roaming Disneyland at night making sure it is kept in strict order, with trash duty at the top of the agenda:

Though park officials wouldn’t divulge how much money is spent on Disneyland’s overall upkeep, they said most is spent on the night shift. … The primary goal of the after-hours crew is to pursue Disney’s vision of an immaculate land, free of the litter and grime of the outside world.

Even if the Disneyland Theory relies on a few extra hired hands to truly sparkle, it would seem like a winning solution for Philadelphia to expand its trash receptacles regardless. We didn’t get the nickname “Filthadelphia” for no reason, after all. More trash bins equals less trash, right? Well, research on the matter is actually a mixed bag.

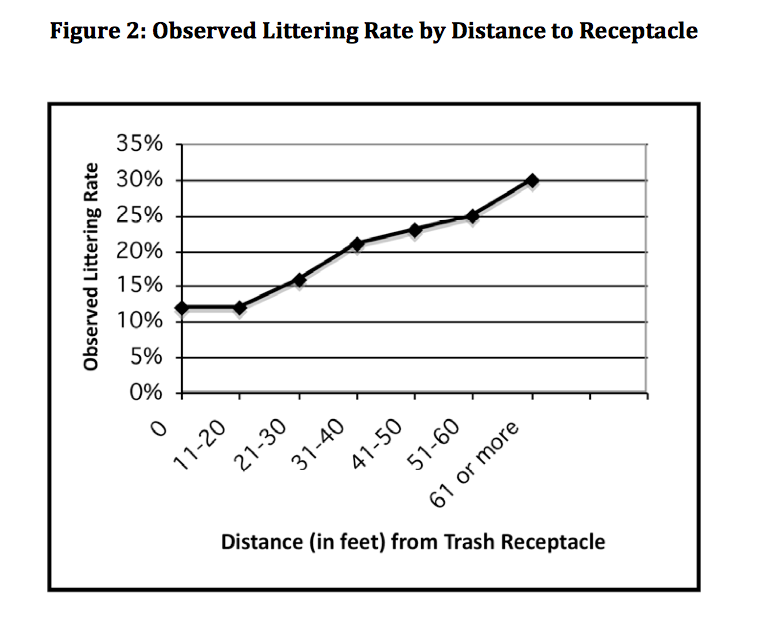

On the one hand, an extensive national study published in 2009 by a Cal State Professor suggests that the majority of littering occurs at a substantial distance from a receptacle. The study looked at 1,000 people across 130 locations in 10 states — including urban, rural and suburban spots — and drew a conclusion that supports both Walt Disney’s research and Brown’s bill:

At the time of improper disposal, the average estimated distance to the nearest receptacle was 29 feet … the observed littering rate when a receptacle was 10 feet or closer was only 12%, and the likelihood of littering increased steadily for receptacles at a greater distance.

But at the same time, the study found that most littering was due to “notable intent” from individuals, more so than their surroundings — say, lack of a trashcan. Only “15 percent of the variance in general littering behavior was due to contextual demands, and the remaining 85 percent resulted from the individual.” This suggests that adding trash bins is only effectively when there is sufficient buy-in from the public. And if individuals actually buy in, perhaps adding more trash cans is superfluous.

Experimental programs have shown that fewer trash bins can lead to a downtick in littering as well. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources began removing hundreds of trash cans back in 2009, and in turn, park rangers reported substantially less trash. A similar initiative conducted by New York’s MTA began back in 2011. After removing trash cans at two subway stations, littering dropped by more than 50 percent. Since then, the program has been scaled up to 10 stations, then 39, after continued success.

It’s difficult to gauge why Philadelphians litter so much — whether it has more to do with access to trash cans or a collective void in environmental attention. Whichever is most to blame, the problem won’t be solved exclusively with Brown’s new bill. We may need more legislation — like a prospective plastic-bag tax bill — to reduce our trash production, even if Mickey helps us find better ways of getting garbage into the can.