What’s Your Problem With Michael Nutter, Philadelphia?

Photograph by Neal Santos

Michael Nutter has recently finished his second glass of sangria at a soul-food joint on South Street when he starts talking about Donovan McNabb. The precise reason for the name-drop isn’t particularly relevant. What follows, more so. “I think he, as some other athletes, has a complicated relationship with Philadelphia,” Nutter begins, shaking his head.

He goes on: “This is a tough town.” He repeats himself: “This is a tough town.” Then he repeats himself again: “Tough town, tough town.”

Jacket removed, fried poultry consumed, the Mayor at 10 p.m. has evidently entered the real talk portion of the evening. “Philly has tremendously high expectations,” Nutter continues, lowering his voice. “But it’s a town that deeply appreciates effort. It’s about sliding into second base hard. It’s about running out a ball hard, even on an out. It’s about stretching your body across the middle knowing you’re going to get slammed to the ground. When you do those things in this town, people will love you and appreciate you forever.” As it turns out, this particular disquisition has less to do with the former Eagles quarterback and more to do with Nutter. “That’s not only on the sports side,” he elaborates. “It’s also in politics. People know I care.”

And yet despite his theory, despite the caring, Mayor Mike Nutter is neither particularly loved nor appreciated by his city. Two weeks before we sat down to dinner, Nutter was booed several times during a Temple University rally for gubernatorial candidate Tom Wolf, including once when his name was mentioned by the President of the United States. (The President, momentarily lacking poker face, proceeded to laugh.)

Even those with only a passing interest in Philadelphia politics shouldn’t have been surprised by the Temple episode. Nutter’s relationship with the city’s public-sector unions, if we wish to be polite, might be described as “strained.” (A throng of their members drowned out his 2013 budget address with — what else — raucous booing.) Same deal with City Council. Really, the whole city is weary of Nutter. His approval rating stood at 39 percent in the last public poll, and was just 30 percent among black Philadelphians. “If you’re asking me to call up someone who’s a Nutter ally,” says one Philadelphia-area U.S. Congressman, “I can’t name one person. Maybe they exist, but I really don’t know.”

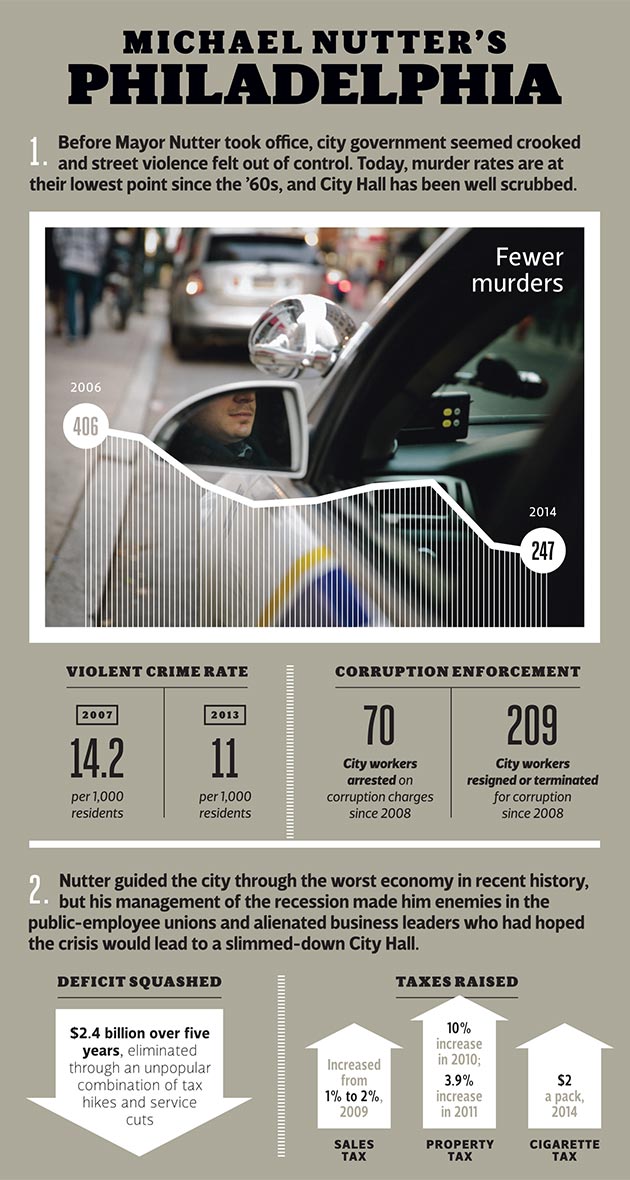

In this context, Michael Nutter’s evocation of Donovan McNabb takes on new meaning. Statistically, there has never been a better Eagles quarterback. But something about him — the passive-aggressive demeanor, the rumored Super Bowl puking — proved off-putting. A similar paradox — above-average results met with below-average approval — plagues Nutter. The city’s population has grown in every year of his mayoralty, reversing a half century of decline that lasted until just before his election. The homicide rate this year is down 36 percent from 2007. The city’s upgraded bond rating — A+, the highest in decades — would be a notable achievement even if it hadn’t been earned in the wake of the 2008 recession.

In the broad-strokes department, Philadelphia’s executive branch has evolved from a pay-to-play pigpen to an exemplar of high ethics (the courts and the row offices are another story), while the city at large has morphed into a creative-class Eden, replete with all the requisite New Urbanist attributes, from accessible waterfronts to bike-able corridors to well-executed sustainability plans. The area in which the city has struggled most — public education — is the one Nutter has had the least control over. “A lot of what this administration is about,” says Nutter’s old friend and adviser, Saul Ewing lobbyist Dick Hayden, “is embracing the notion of what a modern city in the United States should look like.”

It runs deeper than that. Nutter’s Philadelphia has, in many ways, assumed the character of its mayor. The race-neutral political triumph, the aesthetic and environmental polish, the City Hall colonoscopy, the sudden whiff of cosmopolitanism: Michael Nutter’s goo-goo triumph can’t be disentangled from the earnest idealism of the yuppies and immigrants who have fueled the city’s recent growth.

Nutter, accordingly, has become something of a golden boy outside of Philadelphia. Last month he was invited to the White House to talk Ferguson, Missouri, with the President. In 2012 he addressed the Democratic National Convention. His buddy Michael Bloomberg calls him “one of the country’s most dynamic mayors, and a guy I’ve found a lot of common ground with over the years.” Nutter, 57, named one of Governing magazine’s 2014 “Public Officials of the Year,” would seem an obvious source of civic pride for a city whose last mayor landed on Time’s list of “Three Worst Mayors in the Country.”

Nonetheless, nearly everyone I spoke with while reporting this piece, from career lobbyists to former administration bright-young-things to members of the Mayor’s inner circle, seemed wistfully disappointed in Nutter. “I get torn all the time between feeling bad for him and getting pissed at him,” says Councilwoman Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, basically speaking for the rest of the Philadelphia political establishment. “It’s just because I expected more.”

And so assessing Michael Nutter’s legacy isn’t about tallying legislative wins and losses, but explaining the ambivalence that exists in spite of his record. How, over the course of seven years, did the city’s attitude about its mayor get to this strange place, from thrill-up-leg infatuation to deep-seated meh?

IT’S A GIFT TO journalists penning legacy pieces that the most enthusiastic supporters of Michael Nutter’s 2007 upset special happened to be Philadelphia’s press corps. Here is City Paper’s Nathaniel Popkin, writing unironically in early 2008: “Oh, the bristling, resilient city; we put our faith in one man. Make us beautiful again.” The typically restrained Inquirer couldn’t help itself, either, publishing this swelling description of Nutter’s inaugural address: “For just a moment, his voice cracked and tears came to his eyes. Then Michael Nutter gathered himself, swore the oath of mayor, turned to the crowd, and presented his vision for a ‘new Philadelphia.’”

One of the chief appeals of Nutter’s candidacy, abetted by his unsexy Aflac-duck voice, was the wonk factor. In “Hail to the Nerd,” another City Paper paean published during inauguration week, Duane Swierczynski wrote, “Nerds do their homework. Nerds are ridiculously dependable. Nerds pay attention to details. Nerds are obsessed with getting it right. Hallelujah, brothers and sisters, the nerds are officially in charge.” (The last line appears to be a rejoinder to John Street’s infamous 2002 remark, “The brothers and sisters are running the city!”)

Nutter indeed hired a bunch of nerds from outside city ranks, created new nerdy programs and departments — a Chief Integrity Office, an Office of Sustainability, Philly311 — and actively sought to wipe clean lingering traces of the Street administration. He quickly halted the work of the Neighborhood Transformation Initiative, Street’s signature anti-blight program, citing accounting lapses. He ousted five new Street appointees to the zoning and planning boards, including the former mayor’s son. He replaced Redevelopment Authority boss and electricians union head John Dougherty with Nutter campaign staffer and Penn Law alum Terry Gillen (whom Nutter briefly dated in the late ’80s).

While Nutter’s reliance upon Penn grads irked the city’s less pedigreed pols, the heady atmosphere drew in others who wouldn’t have typically been enticed by a career in City Hall. “I remember emailing with a Nutter person at 3 a.m.,” says Greg Heller, who worked for Nutter in a variety of transition-team posts and recently wrote a biography of Philadelphia planning maestro Ed Bacon. “The conversation went, ‘You’re up at 3 a.m.?’ ‘Yeah, you too?’ It really felt like The West Wing, like we were working as hard as we all could to undo the corruption and cronyism of the Street administration. We were as committed to our leader as they were to Martin Sheen.”

But nine months into Nutter’s administration, when the financial collapse cratered the city’s economy, one of his greatest strengths as a candidate — his aversion to political expediency — turned into a crippling weakness. First, as part of his effort to close what wound up being a billion-dollar budget gap, he proposed closing 11 city library branches, mostly in working-class neighborhoods. Unsurprisingly, those communities felt betrayed, while the media, ever devoted to the printed word, soured on Nutter for the first time. “I had polled city services for years,” says political consultant Neil Oxman, who masterminded Nutter’s media campaign and now gives his mayoralty a “B.” Consistently, he told Nutter, people reported being most attached to firefighters and libraries. “I remember disagreeing with him and talking to him and saying, ‘I think you’re making a mistake.’ Closing the libraries — whoever made that decision was insane.”

Nutter, when the topic inevitably arises, engages in some uncharacteristic self-flagellation. “I have stated publicly numerous times, almost on the verge of tears, that the absolute worst decision in all this stuff that I ever made was the decision about the libraries,” he says. “In 2005, Councilman Frank DiCicco and I were the co-winners of [Library Journal’s] politicians-of-the-year award. I grew up in a library.” The penance goes on for a couple more minutes, as Nutter all but tells me that some of his best friends are librarians.

That said, the logic behind the decision remains a central part of his administration’s ethos. “I’m human; of course I care what people think,” he says. “But I’m not going to allow any level of ego and the deep-seated need to be loved and admired to interfere with a good and proper decision on what’s best for the financial or operational integrity of the City of Philadelphia.”

Several months after the libraries proposal (they never did end up closing; Council prevailed, in the first of many mayoral humblings to come), Nutter reprised his tough-love act, urging Council members to give up their city-owned cars and six-figure DROP retirement packages. It didn’t go over well. “That was, quite frankly, something none of us knew about,” says one member of Nutter’s inner circle. “We found out in real time.” So did Council. When the address was over, says a source who was present, a Councilwoman looked at him as she walked out of the chamber and said, “Well, he succeeded in uniting us.”

Within months, the media honeymoon was over. Among the charges lobbed by the city’s scribe class: political incompetence (why did Nutter waste his dwindling political capital on city-owned Buicks?), questionable hires (schools superintendent Arlene Ackerman) and hypocrisy (nerd Nutter turns on the bookworms). Meanwhile, low-income voters already suspicious of Nutter were busy decrying his proposed cuts at a series of highly unpleasant town halls.

Simultaneously, business elites and fiscal scolds began grumbling that Nutter had whiffed on a transformational long-term deal with the city’s public-sector unions (he punted, signing a one-year agreement) early on, while the public still had his back. “I think when Michael Nutter was elected, his political popularity was at its highest,” says David L. Cohen, Comcast V.P. and, as everyone knows, former mayor Ed Rendell’s chief of staff. “He was in the best possible position to take on the unions at that time. I think he had the most leverage for negotiating a contract.” When Cohen later raised this point with Nutter, he says, the Mayor told him about other compelling priorities, like cost-cutting and improving the ethical culture of City Hall. “He felt there was a limited amount of political capital that he had to expend in the first year, and he wanted to expend the capital on positive change rather than on a war with the unions.” Long story short: By the time the economy started to rebound, Nutter’s political leverage had all but disappeared.

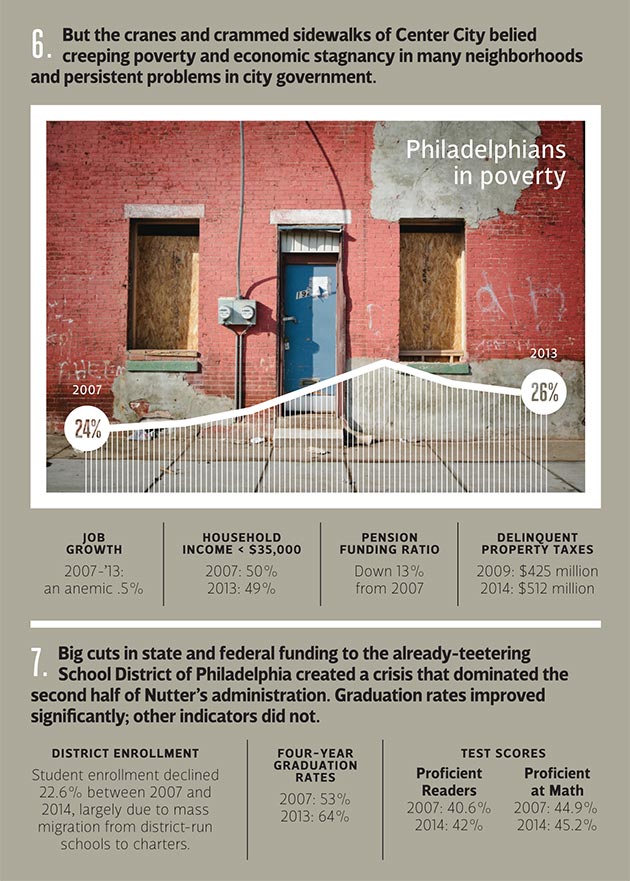

In the real world, outside the political hackocracy, the festering school budget crisis probably did the most to spoil Nutter’s reputation. The Mayor, to be sure, controls neither the entire School Reform Commission nor the district’s purse strings (as he repeatedly pointed out to me, with heavy sighs and exasperated gestures). And he ably plugged some of the catastrophic budget gaps created by state school-funding cuts. But overall, he shrank from articulating a coherent education strategy, or from making schools a major thematic focus. “For whatever reason,” says the Philly-area Congressman, with considerable bafflement, “Nutter was reticent to point out the problems [Governor Tom] Corbett was creating.”

But back in the hackocracy, it’s the car thing that quashed any lingering political capital Nutter had built up during his mayoral campaign. “Personalities play more heavily than the average person realizes,” says former councilman Frank DiCicco, citing the 2009 budget address as the first and most significant fissure between the city’s legislative and executive branches. “In order to be a successful mayor, you need to be a very good point guard,” adds Councilman Jim Kenney, a high-school classmate of Nutter’s and former ally who fell out with him at some undefined point in his first term. “Michael’s more adept at being a Wimbledon Centre Court singles tennis player.”

The bad blood between Nutter and his ex-colleagues, according to the now-familiar narrative, wound up torching the rest of his legacy. City cars were retained, DROP continues to fester, and a healthy chunk of the Mayor’s agenda — comprehensive pension reform, a soda tax, the $2 billion sale of Philadelphia Gas Works — has gone unrealized. As one person who worked to quash the soda tax put it: “At the end of the day, we won because people don’t like Nutter.”

“NO OFFENSE, SON, but that’s some weak-ass thinking.”

That line belongs not to Michael Nutter, but to Bubbles, the junkie from The Wire. Nutter, a Wire devotee who keeps a poster of the show in his office, would recognize the quote. And though he doesn’t put it so tartly, that’s exactly what the Mayor, wearing an olive suit and a salmon bicycle tie, is in the process of telling me one Wednesday afternoon in mid-November.

We’re about midway through an hour-long interview in his office, talking about the car thing. Nutter looks bemused. “I mean, maybe it was seen as a radical thing at the time,” he says. “I don’t care. Keep the car. Do whatever you want to do. I don’t know who has cars today, nor do I care. But I mean, son, move on. You have to move on. That was in 2009. That was five fucking years ago. This is what we’re talking about?”

Half an hour later, as he stands up to leave his office, Nutter steers us back. “Does it strike you as odd at all that adult human beings would be talking about the kinds of things that you mentioned to me, that happened five years ago? I mean, like, you’re still talking about it? As a reason not to engage or just kind of do the right thing on behalf of the citizens of the city?” A minute later, still fixating, Nutter turns to me and stage-whispers: “Isn’t it a little petty?”

The Mayor is right. Objectively, it’s petty and infantile that a group of elected officials would hold a long-standing grudge over a perfectly reasonable request for fiscal prudence amid the worst economic calamity this country has seen in 80 years. But the irony of what he’s telling me is that it will only increase Council’s perception that he’s an arrogant egghead. As a wounded Councilman Bill Greenlee told me, summing up his grievances with the administration, “I think it’s an accumulation, of, like, ‘God, can’t we sometimes have a good idea here?’ You know? Even if we stumbled into it by accident?”

Indeed, the administration line appears to be that Michael Nutter is in possession of the good ideas and isn’t to be held accountable for City Council’s lack of them. “‘Oh, I feel stupid because I only went to high school and everyone else seems smarter than me,’” says Nutter communications director Desiree Peterkin-Bell, mocking a typical councilperson. “No. Like, you need to figure out what your personal issues are and work through them.” (This is the Mayor’s PR person.) One of Nutter’s friends puts it slightly differently: “He doesn’t suffer fools gladly; that’s the bottom line. And Council’s full of fools.”

What all the bickering obscures, however, is that the qualities that make Nutter immune to lasting political friendships, to standard carrot/stick horse-trading, are precisely what made him an appealing mayoral candidate to begin with. If there’s a whiff of elitism about him, well, hail to the nerd; that’s by design. “Michael had very big piles of documents in his office as a city councilman,” says S.R. Wojdak & Associates lobbyist John Hawkins, who previously worked as a Kenney staffer. “He prided himself on reading every document associated with the budget, or any contract that was coming up for Council.” Adds DiCicco: “He’s probably more of a micromanager than he should be. Even when he was a councilman, he maybe had one person in that office he would confide in.”

Nutter, in other words, seemed to consider himself the smartest guy in the room. And he probably was. “But Michael takes it to a different level,” says one political consultant, “because he feels he is not only right on the issues, but that morally he’s right.” It was Councilman Nutter sponsoring most of the do-gooder legislation, like the smoking ban and ethics bill. And back then, as now, he resisted the transactional behavior required to actually get that stuff done. With respect to the smoking ban, he needed DiCicco to broker the compromises and corral the votes. “I gave him a general overview of the things that might be able to get support,” DiCicco says, “and he said, ‘If you can do it, I’d appreciate it.’ So I literally walked over to some of my colleagues in the caucus room. Anyways, I got the votes together, and the bill passed.”

When Nutter ran for mayor — against three machine guys and a self-funded plutocrat — his lack of political connections was cast as a sign of refreshing independence. Early on in his administration, he lost control of that narrative, and he once again became the guy nobody wanted to make a deal with. As a result, some of Nutter’s signature accomplishments — nationally acclaimed policing tactics, a revamped, business-friendly zoning code, a long-overdue property assessment overhaul, an aggressive anti-corruption unit, a pair of vibrant waterfronts — have been dismissed as low-hanging fruit, rather than celebrated as totems of systemic change.

Which gets us partway to solving the mystery of Michael Nutter’s vanishing popularity. “Ed Rendell was brilliant at communication,” says Gillen, who worked for both men. “[He’d] say to voters, ‘I’m going to tell you what I’m going to do. Now I’m going to do it. Now I’m going to tell you what I did.’” Nutter, by contrast, “just hasn’t been as effective as Rendell was at communicating and then bragging a bit about what he accomplished.”

The Mayor doesn’t know how to tell his own story. And everyone else has forgotten he’s got a story to tell.

A LITTLE AFTER NINE o’clock one November morning, Anthony Foxx, the 43-year-old U.S. Secretary of Transportation, is standing at a lectern in a Mantua auditorium, a few feet away from Michael Nutter. Foxx is telling a story about his grandfather, a high-school principal in the segregated South who helped a disadvantaged kid find his way to college. The kid grew up to become a surgeon. It’s a moving story, the way Foxx tells it.

Foxx is in town for an Obama initiative designed to create “ladders of opportunity for boys and young men of color.” When he finishes speaking, Nutter rises to thank him. “I try to encourage folks all the time: Tell your story,” Nutter says. “Everyone has a story to tell.” Nutter then proceeds not to tell his own story, and instead spends the next 30 minutes regurgitating bleakly familiar data points on the challenges facing young black men.

Later that day, as we sit in the backseat of his black Chevy Tahoe, I ask Nutter why he ignored his own advice that morning. A bit lamely, he tells me he didn’t want to upstage Foxx. So I follow up, asking him to tell me the story, if not of his formative years, of his administration. “Probably, ‘He did what he said he was going to do and more,’” Nutter says. “‘Tough times and tough decisions.’ This is considered the worst recession since the Great Depression. … ”

At this point, Nutter’s press secretary, Mark McDonald, jumps in, prodding his boss to say something more inspiring. “I’d go back to his youth and what his parents taught him,” McDonald offers, doing his best to conjure up a West Philly version of a Norman Rockwell painting. “And whether it was about shoveling down the sidewalks, getting up out of the SEPTA bus seat, giving it to an elderly lady, or carrying groceries for somebody coming down the street, all that kind of stuff.” Nutter, clearly not in the mood, obliges and rattles off some platitudes — “Be a good person, be good to other people, treat people well, give everyone dignity and respect, finish what you started” — before moving on.

Nutter isn’t a natural raconteur. And his inability to communicate a coherent narrative about his administration helps explain his political struggles. But his story also happens to be a complicated one to tell. He grew up a rowhouse kid, on the 5500 block of Larchwood Avenue, the son of Catalina, who worked for the Bell phone company her entire career, and Basil, who wandered from job to job before eventually settling down as a plumber for the casinos in Atlantic City. Michael, his younger sister Renée, their parents and their maternal grandmother all lived under the same roof until the kids left for college. “There was no slang allowed in the house,” Renée Messina testifies. “The Nutters were respectable people.”

At the same time, Nutter’s childhood was a turbulent one, rocked by Basil’s alcoholism. “The drinking started when I was about eight and Michael was 13,” says Messina, now a nurse in New Jersey. “He would come home from work and bring a six-pack home with him. It was pretty much an everyday occurrence.” Equally formative for Nutter were his experiences out of the home, at St. Joe’s Prep, which he attended on scholarship and where he was one of only a handful of black students. When he graduated — he was a well-liked goofball with middling grades — Nutter gave his beloved history teacher Jerry Taylor a book of poetry inscribed with a note crediting him as a father figure.

His career, like his childhood, was formed by strikingly divergent influences. Fresh out of Wharton, he worked in the ’80s for Xerox, then for a black-owned investment bank. At night, meanwhile, he was slogging ice buckets at the Impulse Disco, perfecting the “Rapper’s Delight” shtick he still trots out. When Nutter won his City Council seat in 1992, he was shaped on one hand by his good-government mentor, the late councilman John Anderson, and on the other by his crassly transactional sponsor, committeewoman Carol Campbell. (Campbell, before her death in 2008, was one of the few politicians Nutter had trouble saying no to, says one staffer.) Even his district straddled cultural fault lines: On one side of the river, he represented Overbrook and Wynnefield; on the other, Manayunk and East Falls.

The advantage of Nutter’s bipolar political education is that he learned the language of the entire city. The disadvantage is that it can be impossible to figure out what he actually stands for.

Case in point: Nutter’s old boss, Councilman Angel Ortiz, told me his young protégé had been indelibly marked by his experience trying to reason with the radical black liberation group MOVE in the days before the infamous May 1985 bombing. Nutter, following a fruitless conversation with MOVE member Ramona Africa, wound up dodging bullets behind a car with Inquirer columnist Clark DeLeon. When I asked Nutter how the experience marked him, he remarked that “a block and a half burned down, in the neighborhood that I lived in. It was a horrible day for the city, and a lot of people died.” Then he added that he was “not in any way, shape or form criticizing the officials at the time.”

That Nutter would refrain from condemning something so self-evidently catastrophic as the bombing of a city block, a moment after spelling out the extent of the catastrophe, speaks to a pattern of inchoate behavior that persisted after he became mayor. When South Philadelphia High School exploded in racial violence, Nutter stayed mum far too long. When much of the city was calling for schools superintendent Arlene Ackerman’s ouster, Nutter remained ambivalent. Meanwhile, at other junctures, the Mayor chose the most confrontational path possible: Close the libraries, pass this soda tax, sell PGW (now!). His unpredictability began to piss everybody off, and the multi-ethnic coalition that elected him started to fray.

After a couple years of conspicuous silence, John Street began attacking Nutter’s black credentials, while his brother Milton, the ex-con, mounted a 2011 primary challenge premised on the perception that Nutter was indifferent to black Philadelphia. At the same time, Chamber of Commerce types distressed that the city wage tax stands at 3.92 percent and not zero percent seemed equally bummed out; one prominent biz-dev-type laments that Nutter campaigned as a “new democrat” and governed as an “old democrat.” Incongruously, Nutter is also loathed by the city labor unions, who accuse him of being a closet Republican. Cathy Scott, the former president of Philadelphia’s white-collar union, told me she aggressively lobbied national labor leaders to ensure that Nutter didn’t get a post in the Obama White House.

Gillen, who worked on Nutter’s 2007 campaign before joining the administration, tells me a story that neatly encapsulates Nutter’s message-confusion problem. “Michael has never liked beer, because his father drank beer and his father was an alcoholic,” she says. “My whole life I’ve known him, he wouldn’t drink beer. During the campaign, he would go into bars and order wine — chardonnay. Finally we said to him, ‘Could you at least order chianti?’” What appears to be a Chestnut Hill play is, in fact, deeply rooted in Nutter’s West Philly background.

OUT OF THE TAHOE NOW, after a comically brief drive from City Hall to the Bellevue, Nutter lopes up the stairs of the hotel and into a conference room where a group of salespeople push chicken parm sliders around on their plates. Some sort of merchant meeting is taking place, organized by his friend Mary Dougherty, who owns two Nicole Miller boutiques in Philadelphia. Nutter, as he puts it, wants to pop in “to do a little rah-rah.” “Everybody!” Dougherty announces when Nutter walks in. “Mayor Ed Rendell!” She blanches. “Oh my God. Kidding!”

Dougherty insists she was joking, but it’s impossible to ignore the subtext in the remark: Rendell, who despite a lackluster second term left office in 2000 with a 77 percent approval rating, looms over Nutter’s legacy. On the merits, this is puzzling, since the downtown renaissance Rendell presided over pales next to the growth of greater Center City that’s occurred on Nutter’s watch. But because expectations were low when Rendell assumed office, and because he inherited and quickly solved a massive fiscal crisis, and because an entire hagiographic book was written about his first term, his savior narrative was assured. Even Street’s legacy, which few remember fondly, could at least be neatly defined. Agree or disagree, numerous people told me, you knew what he stood for. (Depending on the person: “Anti-blight,” “neighborhoods,” “pay-to-play.”)

If we’ve now entered the political twilight zone in which pay-to-play is preferable to not-pay-to-play merely because it suggests a decipherable identity, Philadelphia needs to look back beyond Street and Rendell to find a suitable mayor against whom to measure Michael Nutter. Start with Joseph S. Clark Jr., who governed Philadelphia from 1952 to 1956. The original good-government mayor — he literally campaigned with a broom in hand — Clark busted up a squalid Republican machine and became the city’s first Democratic mayor since 1884. He was decidedly uncharismatic, and disdained interaction with Philadelphia’s unwashed masses. He would never be the transformational mayor his successor, Richardson Dilworth, grew into. But Clark laid the groundwork.

It’s in this context that Nutter is best understood. Like Clark, Nutter assumed office without support from the city’s dominant political party, Council, or organized labor. That he wound up governing as a high-minded reformer, accordingly, should have surprised no one. Equally, Nutter’s inability to cobble together a lasting political coalition — in Harrisburg, in Council, or across the region, as he and many others had hoped — should have come as no surprise. “He didn’t run on, ‘I’m a political insider and I’m going to, you know, work the halls until things get done the way they always got done,’” says Nutter’s chief of staff, Everett Gillison.

Ideologically speaking, Nutter’s policies look just as we should have predicted. The Bloomberg-brand nanny-state-ism — the sin taxes, the 100,000 new trees, the 500 miles of bike lanes — was in evidence in his Council fixation on campaign finance and public health. When I asked his best friend, restaurateur Robert Bynum, to name a political issue that galvanized Nutter early on in his political career, he responded, “Ethics,” without hesitation.

Same goes for Nutter’s Booker T. Washington moralism, which was manifested most prominently in his famous 2011 “Pull up your pants” sermon and again, more recently, when in the wake of the Michael Brown killing he told me he faulted the black citizens of Ferguson for not electing better local officials. “What’s that town? Seventy-something, 80 percent black? What were you doing election night? You live in an 80 percent black town and you got 53 police officers and three of them are black? No black elected officials? What are y’all doing?” Ferguson is actually about 67 percent black, but what matters here is that the lesson Nutter took from one of the most racially charged confrontations in years is not that the system is racist, or that police are out of control, but that black voters didn’t do their job. “You wouldn’t have that issue if you were taking care of business up on the front end,” Nutter says.

That focus on personal responsibility — unusual for a high-profile black Democrat — is merely a reflection of Nutter’s long-simmering centrism. He was a member of the “third way” Democratic Leadership Council, and traveled to New York in August of 1992 as a Pennsylvania delegate for Bill Clinton. Nutter, Hayden says, “embrace[d] what Clinton was trying to do, which was, ‘Let’s reclaim the middle without alienating the left.’”

His relationships with the Clintons, as it happens, would seem to make him an attractive candidate for a post in a Hillary White House, especially since his high-tax mayoralty could preclude any chance of attaining statewide elected office in Pennsylvania. Of course, there could also be a natural opening for him in Congress if scandal-plagued U.S. Representative Chaka Fattah winds up leaving office. “I think he’d be great in Fattah’s spot,” Peterkin-Bell gushed to me at one point. (Hayden, as if people weren’t confused enough about Nutter, told me the Mayor “doesn’t want to run for Fattah’s seat.”)

Nutter shouldn’t be underestimated if he runs. The most memorable campaign ad in recent Philly history is the Oxman spot starring Nutter’s daughter Olivia — now a freshman at Columbia University — as she was deposited by Dad outside the prestigious (but public!) Masterman School. In retrospect, though, another one of his campaign ads deserves more attention: the one in which City Hall’s iconic clock tower is snapped off its base and shaken free of political hacks. In the spot, the candidate promises to accomplish seven things: hire a new police commissioner, conduct a national search for a new schools superintendent, give the inspector general more authority, institute a no-tolerance policy for public corruption, declare a crime emergency, reform the zoning board, and “throw out the bums in City Hall.”

None of the goals were particularly ambitious. But there’s a good case to be made that Nutter accomplished them all. Put another way: The problem with Nutter isn’t his record, but rather the delusional expectations we all had. At the very end of the interview in his office, Nutter turned to me, suddenly curious about his own legacy, and asked, “So, what is the story?” I suggested that for better or for worse, nobody should have been surprised at what he did and didn’t accomplish — that he was exactly the mayor he told us he would be. “Well, I think you’re kind of right,” he said. “Guy said he was going to do some things. That’s what the public voted for. That’s what he did.”

What more did we expect?

Originally published as “Michael Nutter Will Leave Philadelphia Younger, Bigger, Safer and Smarter Than He Found It” in the January 2015 issue of Philadelphia magazine.