From Bomb Scares to Parking Payoffs: Philadelphia’s Top 7 NIMBY Battles

A screenshot from the Great Experiment film series.

“Pennsylvania is timely Case Study A for witnessing the impact of the not-in-my-back-yard movement against casino development,” the Gaming Industry Observer reported in 2009 when both the planned Foxwoods and SugarHouse casinos, despite being licensed, were still stalled after two and a half years. Each of those situations turned out quite differently (see below) but the trade publication chalked up the delays to “fierce local opposition”; Philly doesn’t play when it comes to NIMBY battles.

Assuming we’re in for another couple years of them — now that that Live! Hotel and Casino has been granted a license for its South Philly stadium-area location — it’s worth looking back at a few of Philly’s most notable NIMBY fights, or those that represent a larger NIMBY whole.

Crosstown Expressway

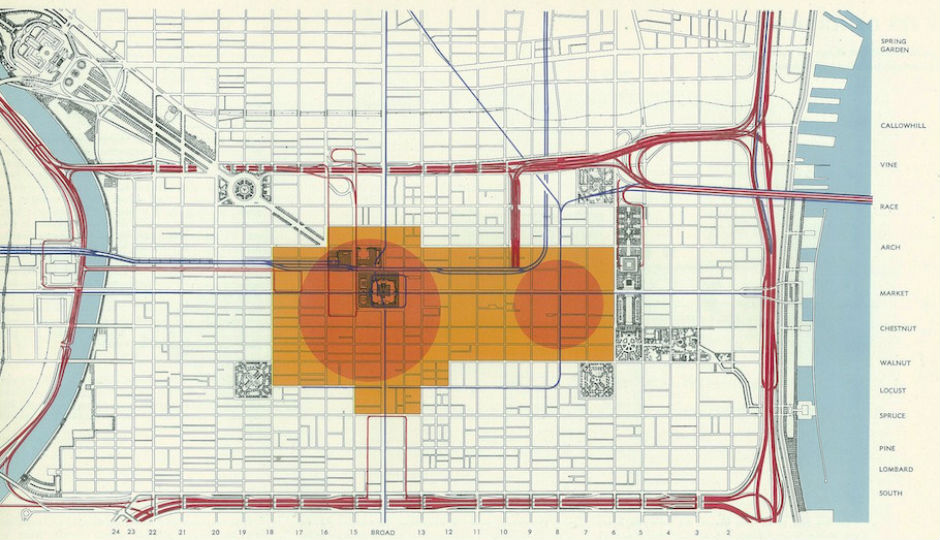

This plan remains so reviled, the City of Philadelphia Planning Department’s staff blog featured it for one of its “Thank Goodness Thursdays” — in other words, “thank goodness it didn’t happen.” The road would have been a connector between I-76 and I-95, involving “most of the space between South and Lombard Street.” It was in play between 1957, when it was approved by the state, until 1974, when it finally died for good. NIMBY fury really heated up in the late 1960s among South Street residents, who saw their property values decline as the project came to closer to reality. It was nixed, then resurrected by Rizzo, then nixed again.

Illustration of the Center City “ring road” system, including the Crosstown Expressway, from the 1963 Center City Plan. Via Planeto.

Biggest objection: The obliteration of entire neighborhoods.

Best resident/developer quote: “While we believe that the expressway has serious shortcomings from a transportation standpoint and would create a racial barrier between Center City and areas to the south, our overriding concern is with the city’s inability to re-house adequately the thousands of low-income families whom the Crosstown would displace.” —Emily Achtenberg of the Delaware Valley Housing Association in 1967

How’d it turn out? All for the best. Or at least better. According to phillyroads, which has a very thorough account of the decades-long issue, SEPTA took the $85 million in earmarked funds for the benighted plan and bought 100 commuter rail cars, 120 subway cars, 190 buses and 110 trolleys.

One Liberty Place

In 1984 developer Willard Rouse shook Philadelphia to its core by proposing a building that would be 61 stories and 945 feet tall, well over the height limit for new construction. Granted, such limits weren’t set down in zoning code, but there was a so-called “gentlemen’s agreement”: No building would be taller than the 491-foot-tall City Hall — the top of Billy Penn’s hat, specifically. Whoever said developers were gentlemen?

Biggest objection: By exceeding City Hall’s height, the building would ruin the city’s historic scale.

Best resident/developer quote: Writing for the New York Times a couple years after its completion, architecture critic Paul Goldberger noted that opponents of One Liberty Place feared it would be “the violent destroyer of a beloved cityscape.”

How’d it turn out? In the same piece, Goldberger called the complete building (left, in a photo from a 1987 issue of Philadelphia magazine) “the finest skyscraper Philadelphia had seen since the completion of the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society headquarters in 1932.” And it was the start of today’s skyline and Center City’s business district.

Baseball Stadium at 12th and Vine

In 2000, Mayor John Street endorsed the idea of a baseball stadium at 12th and Vine — an idea opposed by the Phillies, many city residents, and pretty much every human being in Chinatown, a neighborhood that has been so savaged by development, it doesn’t even have any Back Yard left. (For other Chinatown-related NIMBY battles, look no further than the Convention Center, the Gallery I and II, and the Vine Street Expressway.)

Photo by Rodney Jay Atienza

Biggest objection: The stadium would bring excessive traffic to streets that were already clogged; residents and businesses would be displaced.

Best resident/developer quote: “Using taxpayers’ money to build and upkeep a baseball stadium that will cause harm and damage to an entire community and almost everyone who passes by it is illogical, and may ultimately lead to the self-destruction of the Center City area.” —John Chin, executive director of the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corp., in an Inquirer op-ed

How’d it turn out? Citizen’s Bank Park was beautifully designed by prominent architecture firm Ewing Cole and is a home run in almost every way. Chinatown’s businesses and entrepreneurs have continued an outward expansion north of Vine Street.

Foxwoods Casino

Remember when Steve Wynn was building a casino in Philadelphia? No, not this last time — the time before that. In 2006 a company we’ll call Foxwoods for short got Philly’s second stand-alone casino license, with plans to build on Delaware Avenue. Neighborhood opposition was so fierce, so mighty, by 2010 it was still unbuilt, and Steve Wynn came in with his feathered hair to save the day … or not.

Biggest objection: The casino would be in a residential area with homes, schools and churches.

Best resident/developer quote: “I love the proximity to these people. I love the proximity to the Vietnamese neighborhood. And I’m gonna put in a beautiful Vietnamese restaurant for them.” —Steve Wynn, making some ill-advised remarks about having a casino near an Asian-American neighborhood

How’d it turn out?: The same year, Wynn abruptly walked away from the project, shocking everyone involved, including his own lawyers. Mayor Nutter said, “I’ve never seen anything like this before.”

How’d it turn out? In 2011, the Foxwoods license was revoked. Now, three years and another Steve Wynn flirtation later, Live! Hotel and Casino has it.

SugarHouse Casino

Here’s the flipside of Foxwoods — the riverside casino project that did go through despite NIMBY opposition. Granted a license at the same time as Foxwoods, it faced vigorous, megaphoned and organized protest from Fishtowners and NoLibs residents — NIMBYism complicated by the question of riparian rights. After Mayor Street, who’d green-lighted construction, left office, Mayor Nutter stepped in as hero (briefly, back when Nutter had some heroism in him) and stopped it from being built. Once it was under construction, a group of protesters who blocked work at the site were arrested and put in jail, becoming known as the SugarHouse Thirteen.

Protest by Casino-Free Philadelphia at SugarHouse’s groundbreaking. Photo via casinofreephilly.org

Biggest objection: See Foxwoods objections, above.

Best resident/developer quote: “It’s great when the state fails to suppress citizen action, it encourages others [to speak out]. These are the kinds of actions citizens can and should take.” —Swarthmore professor George Lakey, one of the Sugarhouse Thirteen, after being acquitted.

How’d it turn out? According to Casino Free Philly, Sugarhouse’s first year had a number of negative effects on the city and its citizens rather than the promised bounty neighbors were told to expect. You can look at all the stats they’ve gathered, or you can simply walk inside and feel your soul shrivel up.

40th Street corridor and vicinity

Poster from the movement against the 43rd and Market McDonald’s, which hung in the window of the Toviah Thrift Shop owned by Rev. Falcon. Photo courtesy Upenn Walking Tour.

There are innumerable NIMBY battles pertaining to university development in Philadelphia, but initiatives by the University of Pennsylvania seem to draw the most ire. The development of the 40th Street corridor is notable for a couple reasons: It marked a turning point for Penn’s neighborhood identity (40th Street had been a dividing line for years), and it popularized the term “McPenntrification” when the NIMBY group Neighbors Against McPenntrification mobilized against various projects in the vicinity, most notably a McDonald’s at 43rd and Market (activists maintained Penn and McDonald’s were working on the project together, irresponsibly remediating an environmentally contaminated site).

Biggest objection: That Penn would impose a neo-corporate “Disneyland vision of the world” on West Philadelphia.

Best resident/developer quote: “I think it’s ridiculous. The box was clearly labeled ‘tetrachloroethylene.’ That was just John Fry’s way of discrediting us.” —Neighbors Against McPenntrification leader Rev. Larry Falcon regarding the bomb scare triggered by his mailing a box of dirt to Fry (then Penn’s exec VP).

How’d it turn out? The corner of 40th and Walnut has a mixed record, with some businesses continuing to succeed (like Fresh Grocer) and others struggling to maintain the same ownership (like the movie theater). The McDonald’s at 43rd and Market was defeated by Falcon and co., but there is a Dunkin’ Donuts on that corner, should neighbors require inexpensive eats.

Stamper Square Hotel & Condominium

This was just one of several proposals for the Space Formally Known As New Market between Front and Second, Pine and Lombard. After the very ’70s indoor-outdoor mall failed in the ’90s, it seemed there was no alternative proposal that didn’t get NIMBY’d out of existence. Even Will Smith, who wanted to open a W Hotel there, was unable to pull it off. Stamper Square would have been a 150-room Starwood Hotel and 85-unit condos designed by H2L2.

A rendering of Stamper Square as viewed from Second Street. Via phillyskyline.com.

Biggest objection: Height. The building would have been 17 stories, which some residents felt was out of scale with the historic neighborhood.

Best resident/developer quote: “I have concerns about that. I think you should rise above it.” —Philly Planning Commission’s Alan Greenberger to a lawyer representing developer Marc Stein, who thwarted NIMBYism by promising community residents parking spots if they went along with the project.

How’d it turn out? After elaborate machinations, the deal fell apart. Last year, Toll Brothers built 410 at Society Hill, a much more subdued collection of modern luxury condos on the same spot.

Follow Liz Spikol on Twitter.