Birdie Africa: The Lost Boy

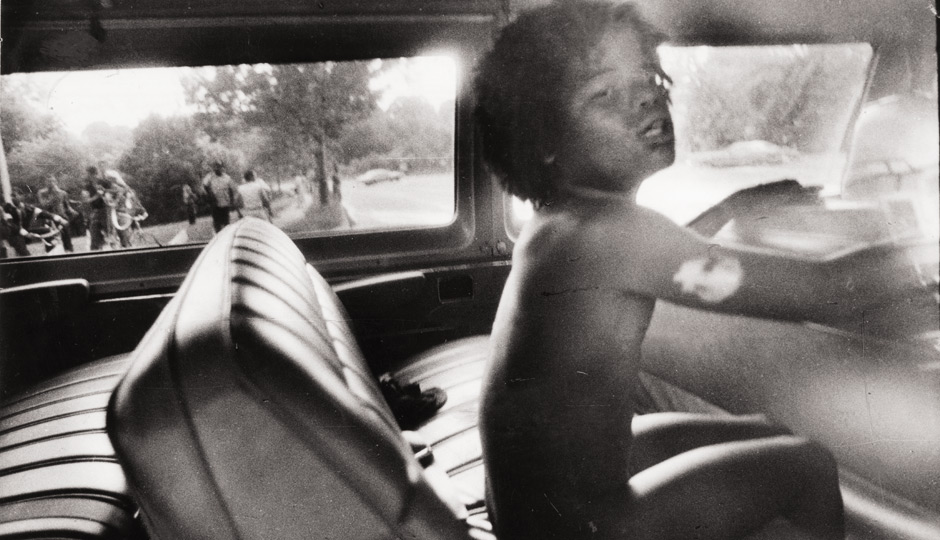

Birdie in the now-famous Michael Mally photo during the MOVE siege, May 13, 1985.

Photo by Michael Mally/Philadelphia Inquirer

HE WENT TO THE FIRE

The city was burning, and he went to the fire and got as close as he could. Something strange had just happened, something that would haunt the city for decades. A police helicopter had appeared in the sky above a West Philly rowhouse. The house was occupied by a black revolutionary group called MOVE. Seven adults and six children lived inside. The copter dropped a satchel onto the roof. The satchel contained four pounds of explosive. The explosion shook the neighborhood; people could feel it blocks away. Michael Mally gazed through his Nikon and took photos, as the flames leapt from home to home to home and the smoke rose in dark columns.

Mally was a staff photographer for the Inquirer. He knew, of course, the basic outline of MOVE—its back-to-nature philosophy, its history of confrontations with neighbors and police. The people inside the house all went by the last name of Africa, a practice begun by their founder and leader, a man born Vincent Leaphart who now called himself John Africa. Africa believed that modern technology had sapped black people of the ability to fight a racist system. In archival footage from Let the Fire Burn, Jason Osder’s astonishing 2013 documentary about the MOVE bombing, one MOVE member says, “We see John Africa the same way that people saw Jesus Christ.”

The police had tried to evict MOVE seven years earlier, in 1978, from the group’s old headquarters in the Powelton Village section of West Philadelphia. At the time, Mayor Frank Rizzo vowed to drag them out “by the backs of their necks”; MOVE members said that if police came in with guns, they would shoot back. The ensuing raid ended in a gunfight that killed one officer, James J. Ramp, and injured a number of other police and firefighters. In 1980, nine MOVE members were convicted of third-degree murder in Ramp’s death and sent to prison.

Now, in the past few weeks, tensions between MOVE and authorities had been rising again. At its new headquarters on the 6200 block of West Osage Avenue, a neighborhood of lower-middle-class families, most of them black, MOVE had built a rooftop bunker that commanded broad tactical views of the street; neighbors had been frightened one day when they looked up at the roof and noticed a man in a mask holding a large gun. Police had been pouring in, and Mally had spent the last few days taking photos of the growing standoff. He’d tried to get close to the house on the ground, but police barricaded the block, sealing off the neighborhood.

So the Inquirer rented a crane. On the afternoon of May 13, 1985, after police bombed the house and the fire started, Mally climbed aboard and let it elevate him 75 feet. Mally had once worked for the Los Angeles Times, where he’d shot a number of Santa Ana brushfires, but nothing like this. Strangely, there were no fire trucks pointing water hoses at the MOVE house, no firemen working furiously to put it out. The fire department and the police had made a decision to let the fire take its course. Flames whipped through brick and wood and drywall, engulfing one whole city block, then two, then three. A word leapt to Mally’s mind: Dresden. The Allied firebombing in World War II. He felt like crying.

At some point, he rejoined the other photographers on the ground. He heard shouting from one of his Inquirer colleagues, a reporter named David Lee Preston, who is now assistant city editor at the Daily News. “They just took a kid in a van—you need to take this picture!” Preston yelled. Mally rushed to a nearby van, threw his camera up against the window. He managed to take one exposure before it pulled away.

Later that day, in the paper’s darkroom, the picture emerged. It was horribly backlit, and the contrast was poor, but the figure in the foreground was unmistakable: a naked boy, seemingly eight or nine years old, sitting in the backseat of a van. There was a large white splotch on his right arm—what looked like a fresh burn—and his hair fell in dreadlocks. His mouth was open.

By then, five children had died in the fire, as well as six adults, including the boy’s mother, Rhonda Harris. The boy, known inside MOVE as Birdie Africa, was one of only two members to escape; the other was an adult woman, Ramona Africa.

Mally looked at his photo of Birdie Africa in awe and horror. The boy had just survived an unthinkable trauma—and now he was going to have to deal with the aftermath, with the burns and the bad dreams and the loss of his mother, entirely alone. How could he ever cope? How could anyone? What kind of life was this kid going to have?

AROUND THE TIME Michael Mally was shooting his soon-to-be-iconic photo of Birdie, Don Nakayama was doing his rounds at Children’s Hospital, about 30 blocks east. Usually when Nakayama did rounds, the TVs above the beds were tuned to cartoons. Today was different. In every room, the TVs were tuned to live news images of a massive fire.

It was dusk. Nakayama, the chief resident, glanced out one of the hospital’s windows and saw warm orange light rising above the city in the distance. Soon, he thought, he would be busy. Nakayama and his colleagues began to prepare for the burn victims who would surely be coming.

After a time, a small boy arrived in the ER. He smelled like soot, and 20 percent of his body had second- and third-degree burns. But he seemed to have escaped the main conflagration. More than the soot and the burns, what struck the doctors about the boy was his stunted shape. Hospital staff guessed he was nine years old; he was actually 13. (MOVE and Ramona Africa, the other survivor of the bombing, have always vigorously contested the suggestion that Birdie was malnourished. Africa says she remembers that Birdie once ran from 62nd and Osage all the way to Chester, Pennsylvania—a distance of 13 miles. “Birdie ate a strong, healthy diet,” she recalls in a phone conversation. “He ate raw food, roots, potatoes, vegetables, spinach, he ate fruit, he ate raw peanuts—the diet that MOVE was criticized for but today doctors are saying is the best diet to have.” In a letter from prison, Phil Africa writes, “I remember Birdie as the little kid with the loud clear laugh who was strong as a bull and loved eating grapes (smile). … You would have to see Birdie with his long thick healthy locks and his big glowing smile & happy face to really know the Birdie of MOVE (smile).”)

At Children’s, the doctors gave Birdie morphine, rinsed his burns in saline, applied ointments and dressings. “He had been through what most people cannot imagine,” Nakayama said in a lengthy 1988 Inquirer article about Birdie’s recovery, published before the dawn of strict medical privacy laws, when hospital workers could speak more freely. “But it was remarkable how cool he was.”

The ER was quiet; no additional children arrived. Either the fire wasn’t as bad as it looked, or Birdie was the only child who’d survived it. That night, Birdie was resting in a bed in his own room when a social worker named Toni Seidl came in to check on him. She was “horrified to find Birdie quietly watching the MOVE disaster,” according to the same article. “She changed the channel to a Popeye cartoon.”