The Trouble With Harry Jay Katz

It’s a sultry summer evening, and the pulse of Philadelphia night life is flat-lining. By dusk on this Monday, most of the dwellers of America’s fifth largest city have already tramped home. Jaywalkers on Broad Street pause in the middle of the city’s most famous boulevard for aimless chitchat without fear of vehicular homicide. A valet stands idle, rhythmically tossing and catching a lone set of keys. It’s no different inside the Palm, a sirloin and potato establishment popular with the folks who rule this town. But at 8 p.m. sharp, the mood goes from tepid to warm. Harry Jay Katz has arrived.

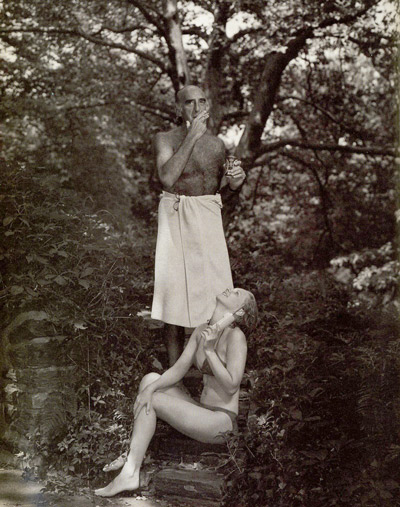

“Hey, Bubbie!” Katz shouts to one and all, leaving behind a trail of camaraderie and cologne. The hostess is smooched, the bartender back-slapped. The 56-year-old Katz sports a Saturday Night Fever-era black shirt. Three buttons are undone, exposing a plush rug of curly white hair. His retreating hairline divulges a sunburned pate. In the back, there are longish silver strands that flip upward like feathers. With his beakish nose and sharp eyes, Katz is the American bald eagle incarnate. Curiously, his face is not among the caricatures on the restaurant’s walls. “I overslept the day they were drawing,” he says. But first things first. He buys a round of drinks for the party at the other end of the bar. They are a trio out of Mario Puzo’s imagination: a heavily mascaraed, frizzy-haired beauty; a no-neck lawyer in a dark suit; and a man sporting white shoes, a bad toupee and a severe eyelid tic. “Those guys are connected,” whispers Katz, pushing his putty-like nasal cartilage to the side with his right forefinger. “The least I can do is buy them a fucking drink.”

Katz begins chain-smoking Camels. He brushes off the complaints of friend and cardiologist Dr. Ronald Pennock with a Borscht Belt “I die, when I die.” Amidst all the merriment, Katz has forgotten to order himself a drink. He requests a martini fuelled by Ketel vodka. The bartender pours the ingredients into his trusty shaker. “Hey, make sure you shake it up by your ear,” implores Katz. “Don’t give it a pussy shake, give it a shake.”

It’s another night out on the town for Harry Jay Katz, Philadelphia’s geriatric libertine. The guy who kibitzes with Schwarzenegger and Stallone. The Don Quixote dealmaker behind a bushel of ballyhooed failures, beginning with the never-opened Playboy Club of the 1970s and ending with last year’s neverpublished book on what really happened to Jimmy Hoffa. A prankish sorcerer who magically insinuates himself into nearly every aspect of Philadelphia lore. Sure, everyone remembers that some woman drowned in his hot tub while under the influence of cocaine and antidepressants, but that was 2 years ago, and Katz is a man who lives in the hyperpresent. The games must go on.

Just now, a long-haired blonde walks by wearing CK ONE, a tight black dress and stiletto heels. Katz moves into action. He’s flying solo tonight, and it makes him itchy. “You know, I had hair just like that,” he calls to her. “Then it all fell out. What’s your name?” The young lady looks at him quizzically, stutter-steps backward, pirouettes, and canters away. Harry, callous to the anguish of rejection from years as a singles warrior, shrugs, and gives his best Alfred E. Neuman “what, me worry?” smile. Still, a waiter friend gives Harry the raspberry. “Hey, Harry,” he says, “you’re losing your touch. Three years ago, she would have been sucking your cock at the bar.”

HE’S BEEN CALLED a Gadfly with a multi-million-dollar trust fund. Zelig before Zelig. The ultimate dilettante. No one has squeezed more lines of type out of stillborn projects, a shuttered restaurant and roguish behavior than Harry Jay Katz. Today, politicians duck his calls. He reeks of two botched marriages and a black book flush with the names of women who would love to witness his slow castration.

Still, Katz remains an undeniable and unpredictable presence in Philadelphia. Foes grumble that he has never held a real job. They’re wrong. Being Harry Jay Katz is a full-time job. You have to work at it. There are the choreographed late nights. The mornings spent calling columnists— primarily his friend Stu Bykofsky of the Daily News— to pass on a gossipy tidbit. Then there’s his street rep as an incorrigible womanizer. That requires long hours of indefatigable maintenance.

The fruit of Katz’s labor can be found by his toilet. Katz’s celeb ties are on display in the tiny downstairs bathroom of his East Falls home. Above the throne is Maria and Arnold’s framed wedding invitation. On the right wall is a large photo of Katz and his second wife, Andrea Diehl, at the wedding of Sylvester Stallone and Brigitte Nielsen. To the left, there’s a Polaroid of Sly with Girl Scout cookies bought from Katz’s daughter Jessica. There are letters from George Bush, Bill Clinton, Gerald Ford, and Lyndon Johnson. (He’s dined at the White House under three presidents.) Down to the right is an invitation to a fund-raiser the Katz family held for District Attorney Lynne Abraham. That’s the image Katz has painstakingly created. The bon vivant. The last boulevardier. The man about town. Philly’s connection to the stars.

But there’s another image of Harry Jay Katz that no amount of self-promotion can burnish. It’s an ominous picture of a playboy prince of darkness. Part of Katz’s less-charming underbelly was exposed with the 1995 drowning of Valerie Sheridan in his hot tub, and the attempted suicide of Susan Delplanque the next day. More is revealed in court documents. In 1994, Katz was found liable of sexual harassment. In a separate 1996 case, he was accused by another woman of physical abuse and intimidation. Three women who know him say part of his problem is cocaine. In April, a Philadelphia Family Court judge ordered him to pay child support for a son he fathered out of wedlock. In an effort to evade paying for his sins, Katz, a man who continues to live in a mansion and dine at Philadelphia’s most expensive bistros, declared bankruptcy in 1995. He claimed to be worth only $150. “He’s failed at everything he ever tried,” says one former friend. “He even failed at suicide.”

But for Harry Jay Katz, the party goes on.