PHOTOS: Bernard Hopkins, Philly’s Ultimate Champion

What makes the myth of Bernard Hopkins special is how it continues to grow in unpredictable ways.

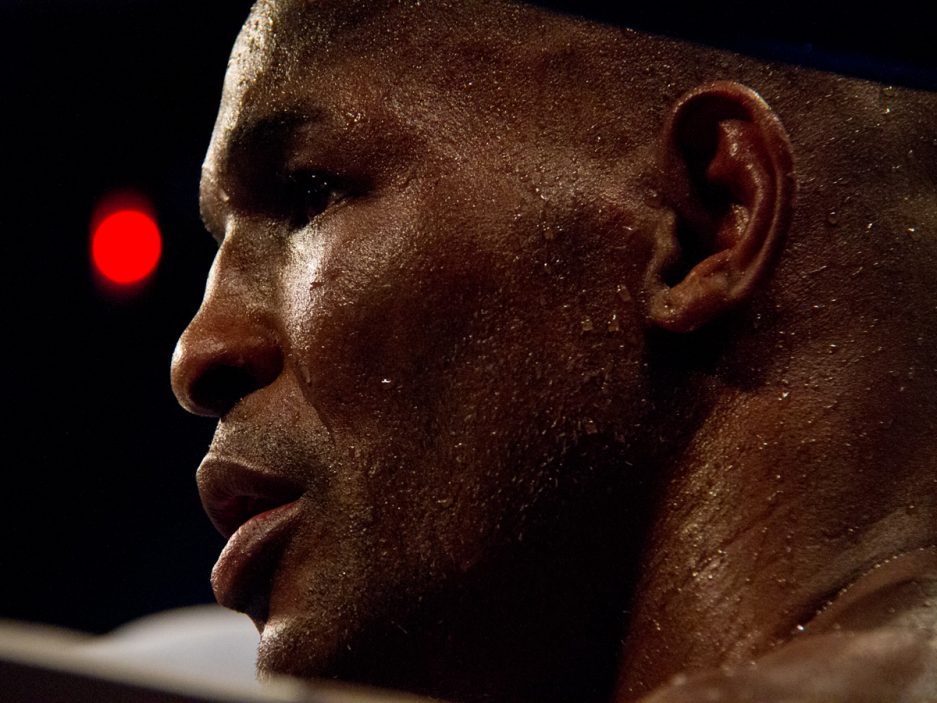

Even on a routine night when it seems there’s little to gain—at least as much as that’s possible for the oldest fighter ever to defend a major world championship against yet another opponent young enough to be his son—the 48-year-old Germantown native is able to defy expectations. He’s done it so consistently it’s hard to keep track, and thus we take him for granted.

The latest example is Hopkins’ unanimous-decision victory against the unknown Karo Murat on Saturday night at Boardwalk Hall, an event that no one expected much from. Murat, an Armenian from Iraq who lives in Berlin, hadn’t fought in a year and a half and entered as a 6-to-1 underdog. Hopkins only took the fight because the IBF had inexplicably designated the 30-year-old its mandatory challenger. To put the chasm in experience between them in perspective: It was Murat’s 28th professional fight; it was Hopkins’ 30th world championship fight.

Yet boxing’s elder statesman improbably wound up delivering his most exciting, fan-friendly performance in years, one that had the partisan crowd of 6,324 on its feet throughout the night.

Hopkins’s fights, particularly in the twilight of his career, have adhered to a familiar, measured pattern. He’s typically been content to land a single well-timed shot then clinch, hold and hit, or otherwise roughhouse his opponents. They’ve been more didactic experiences in the outer limits of sweet science than thrillfests: exhibitions of a master craftsman, tactician and psychological warrior at work. As he’s continued to take on all comers well past his 40th birthday, Hopkins’ spoiler tactics may have been necessary to “get the W” against younger, stronger, primer opponents, but they’ve hardly endeared him to casual fans.

Yet there was nothing boring about Saturday night.

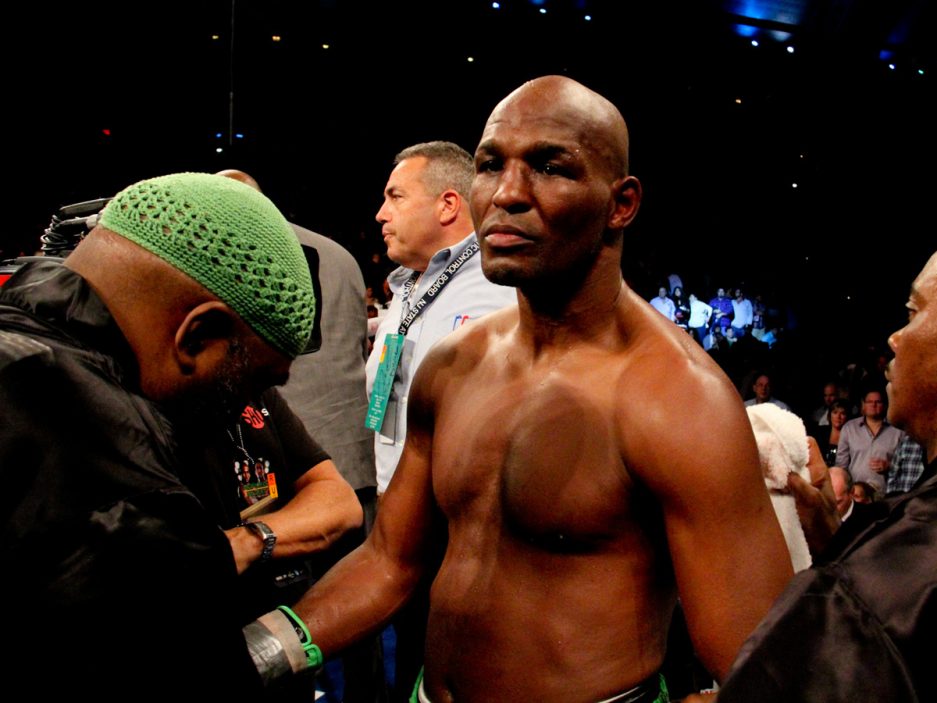

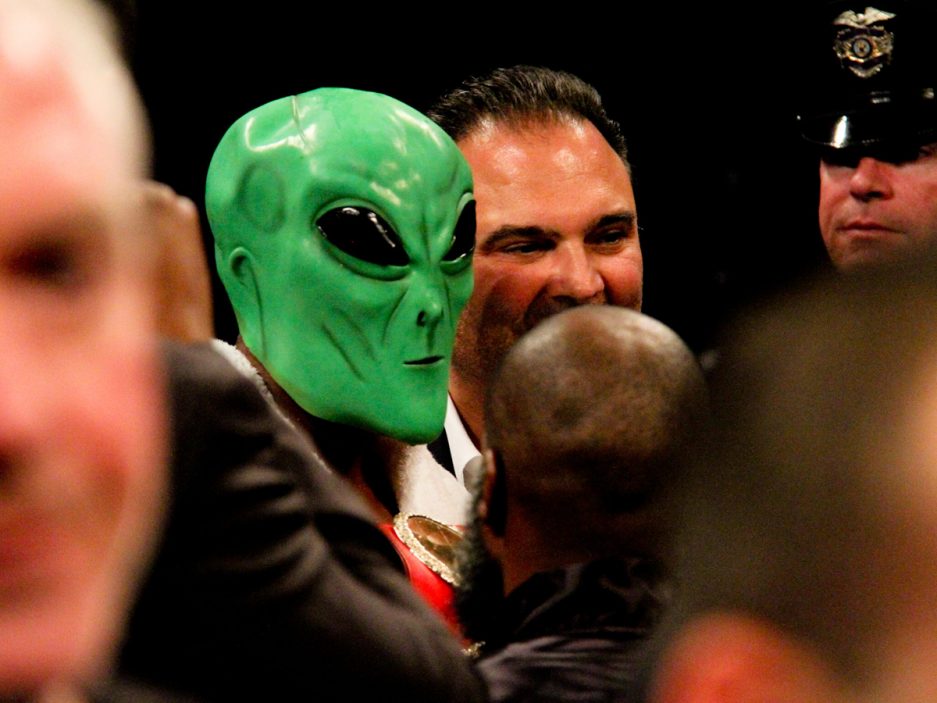

Hopkins, for more than two decades known as The Executioner, has traded in for a new persona — The Alien — to emphasize his otherworldly longevity. (Consider that Appetite for Destruction was America’s No. 1 album when Hopkins made his pro debut in 1988.) As he approached the ring at 10:45 p.m., he wore a campy lime green alien mask alongside longtime trainer Naazim Richardson, whose matching crochet taqiyah was a nice stylistic touch.

But when the bell rang, the first three rounds were all Murat. The challenger’s game plan was sound: to make Hopkins work the full three minutes of each frame and test his stamina. He was there to win. The sparse activity was conspicuous even for Hopkins, a traditionally slow starter, yet it would prove to be part of the plan.

“[The passive opening] was the bone on the string so the dog would follow it into a dark alley and didn’t realize someone was waiting on him — and that was me,” Hopkins explained afterward. “I led him on.”

From the fourth round on, Hopkins’ work rate increased and he began to find range with his jab and the lead straight. He slipped, he ducked, he rolled his shoulders, he countered brilliantly. He started to put his punches together and back the challenger up. He beat Murat down in the seventh, eighth and ninth, standing in the pocket and brawling and getting the better of the two-way action. He twice had the challenger hurt and on the ropes and looked poised to score his first knockout since that devastating body shot — “chopped liver with Hopkins sauce,” he cheekily dubbed it — that subdued Oscar De La Hoya in 2004.

These were the types of hellacious exchanges so rare in Hopkins’ bouts: because he’s so adept at neutralizing his opponent’s offensives and typically hesitant to trade recklessly himself. “I’m a Philly fighter, and that means that if you bring out the dog in me, I’ll bite down and do what I have to do to win,” he would say.

“I’m not the biggest puncher in the world, but I can get your attention.”

Hopkins is no stranger to gamesmanship. He’s spent most of his career demonstrating the value of getting into opponents’ heads, most notably the time he did push-ups between rounds in his rematch with Jean Pascal when the younger champion was slow to emerge from his corner. No veteran trick was left in the bag Saturday night, as Hopkins unsettled, frustrated and intimidated his opponent at every stage: He caught the challenger with a surreptitious rabbit punch when his back was turned in the second and kissed him on the back of the head coming out of a clinch in the fifth.

The most memorable salvo came in the eighth. As he peppered his opponent with punches and opened a cut over the corner of Murat’s left eye, Hopkins deliberately backed into the challenger’s corner and began talking to his corner men all while parrying and countering Murat’s punches (below). No one at ringside could recall ever seeing anything like it. Chants of “B-Hop! B-Hop!” echoed throughout the arena. When the bell rang, Hopkins didn’t sit down between rounds.

“I was talking to his corner, trying to negotiate with them to stop the fight,” Hopkins explained. “This guy was coming, bleeding and taking a lot of punishment. … I looked at the corner, I said, ‘This guy’s all cut up, I’m going to keep beating him, and it’s going to get ugly.’ That’s what I did. They didn’t listen, though.”

Hopkins — who’s never been beaten up, never been cut in a fight, stays in fighting shape 365 days a year and keeps a 31-inch waist — looked as fresh in the final round as he did in the first.

His legacy was already bulletproof. Has been for years. From 1995 to 2005, he made a division-record 20 defenses of the middleweight championship — more than Marvin Hagler, Carlos Monzon or Sugar Ray Robinson. Since then, he’s moved up to light heavyweight and had three separate title reigns. Divide his career in two and, incredibly, either half is Hall of Fame-worthy on its own. Saturday’s fight will represent a brief chapter in the Russian novel of Hopkins’ panoramic career — which stretches back to the Reagan administration — but he managed to make it a memorable one.

What’s next for Hopkins as he approaches AARP eligibility is anyone’s guess. He spoke boldly of unifying the light heavyweight titles to become undisputed champion at 175 pounds. He wants to fight past his 50th birthday, which is just 14 months away. He even talked seriously of boiling down to 160 pounds — the weight class he ruled for so long — for a meet-me-in-the-middle megafight with Floyd Mayweather Jr., boxing’s pound-for-pound champion.

Whatever happens, just don’t be surprised.

Bryan Armen Graham has written for Sports Illustrated, The Atlantic and The Village Voice. You can follow him on Twitter at @BryanAGraham.