Temple Shows Its True Colors in Bringing Students Back to Campus, Causing COVID Outbreak

It’s time to stop thinking of universities as altruistic civic institutions. They are businesses. Nothing more, nothing less.

Temple University tried to have in-person classes this fall, but just 10 days into the semester, the school had a COVID outbreak on its hands. Photo by Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

When the coronavirus pandemic first hit the United States, it became virtually impossible to read a story about the present moment without bumping into the phrase “these uncertain times.” Despite the fact that this is an all-time bad cliché, it’s not exactly wrong: Much of 2020 has been uncertain. Who among us could have predicted the world-stopping pandemic?

Just because many of these “times” are “uncertain,” though, does not mean that everything right now is unpredictable. For example, if I were to ask you: What is likely to happen if you are a university that decides to bring its students back to campus in the middle of a pandemic?, you would probably (correctly) conclude that it would prompt a COVID-19 outbreak. It’s a bit like that old Wikipedia game where you click on the first link at the top of each page and almost always eventually end up on the page for Philosophy. When it comes to in-person college right now, there is one road, and it leads to one conclusion: Bad idea.

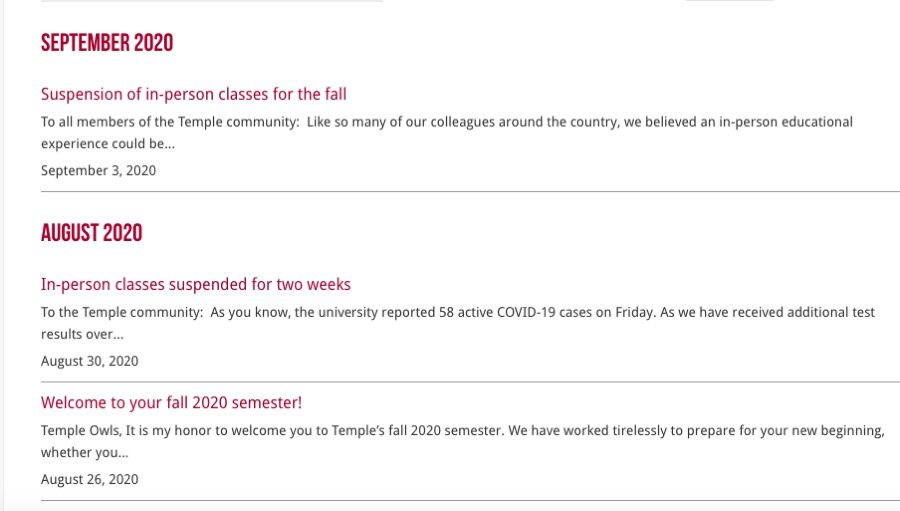

Which brings us to Temple University and its decision to bring 9,000 students back to campus in order to resume a number of classes in person, starting on August 24th. It went … well, instead of explaining it, allow me to direct your attention to Temple’s own announcements page, which presents the story of a catastrophic faceplant in three succinct acts:

Act 1: August 26th, SUBJECT LINE: “Welcome to your 2020 fall semester!”

Act 2: August 30th, SUBJECT LINE: “In-person classes suspended for two weeks.”

Act 3: September 3rd, SUBJECT LINE: “Suspension of in-person classes for the fall.”

A story of failure, told in three university-wide communiqués.

By the time of that last message, Temple had already backed itself into a corner. The city reported 235 new cases of COVID-19 on September 2nd, its highest single-day total in weeks. The Health Department had also held a mass testing clinic at Temple two days before, which yielded 60 cases and a positivity rate of 15 percent. (For comparison, the city’s positive rate had been around five percent for much of the past month.) All told, Temple has reported 350 total cases. “It does appear that most of the increase in the past week that we’ve seen in the city is related to the outbreak at Temple University,” health commissioner Thomas Farley said at a press conference last week.

The news over the past few months should have indicated to schools, in flashing neon lights, that reopening for in-person classes in the fall would lead to disaster. Huge swaths of the country continued to report high case counts. The virus is spread most easily in close-contact, indoor spaces, which sounds quite a bit like, you know, classrooms, dormitories and off-campus housing. Not to mention the rapidly accumulating evidence, from other universities who tried reopening before Temple, that it was simply not possible to have college without COVID. As early as late July, the University of Southern California reported an outbreak on its fraternity row. North Carolina and Oklahoma State reported campus outbreaks a week before Temple’s official first day of classes, too. Drexel, whose semester was scheduled to begin on September 21st, apparently read the writing on the wall and canceled its own plans for reopening campus. Temple went ahead anyway.

It might be tempting to write this whole ordeal off as an unfortunate instance of good planning gone wrong. Certainly that is what the city is trying to do. “Temple did everything we asked them to do in advance, and they were very successful in preventing spread in classrooms, in dormitories, and in cafeterias — all the things that happen on campus,” Farley said at last week’s press conference. “What occurred here, really, were things that were very much out of their control: Students living off campus.”

This line of thinking is ridiculous. Temple absolutely should be held responsible for what happened off campus, seeing as it decided to invite 9,000 people, from all over the country, back to campus for in-person instruction, knowing that many of them would live off campus.

Any freshman taking an Intro to Infectious Disease class could have told you that the resumption of in-person classes was a terrible idea from a disease-prevention standpoint. Universities are supposed to be staffed by smart people. How does a decision like this end up getting made?

Part of the problem is our own classification error. We tend to think of universities as civic institutions that have little self-interest beyond producing the next generation of engaged, educated citizenry. In that telling, it’s difficult to reconcile the image of the ethical, altruistic university with one that brings students back to campus knowing it could very well prompt an outbreak of highly contagious disease. (Temple has said that it knew an outbreak was a possibility; similarly, when Oklahoma State reported its 23-case outbreak at a sorority house, a spokesperson for the school nonchalantly called the news “expected.”)

But the truth is, universities aren’t concerned with anything outside of themselves. They are businesses. Seen through this lens, cleansed of the false coat of ethics, Temple’s decision actually starts to make some logical, albeit twisted, sense.

See, a business concerns itself with profits over consequences, so long as its behavior doesn’t explicitly run afoul of any established rules. This is why most airlines have been booking middle seats on planes, even though anyone with a pinch of common sense would tell you this is ill-advised. Much in the same way, Temple was allowed to reopen, per the rules set out by the city Health Department. A business also doesn’t mind bad P.R. as long as that negative P.R. is preceded by a massive bout of money-making, which Temple was hoping to achieve by charging its students full tuition, and renting out its dorm space. Attention spans are short, and one “contrite” apology is usually enough to make people move on. (Facebook is the master of this apology laundering.)

Temple had every reason to suspect this outbreak was going to happen. Its very own professors, through the university faculty union, feared an impending outbreak and pleaded with university administrators not to force them into teaching in person. Temple professor Laurence Steinberg also provided what should have been a warning in an op-ed he wrote in the New York Times. Steinberg, a psychologist who studies the brain chemistry of young adults, explained exactly why this outcome was all but assured: college students simply can’t be trusted to properly socially distance. Steinberg’s point isn’t that this is the fault of the students; it’s that college students are mentally predisposed to making short-sighted, poor decisions. It’s not the job of the students to prevent a coronavirus outbreak; it’s the job of the adults in the room to prevent them from even having the opportunity to screw up in the first place.

Even now, Temple hasn’t fully reversed course. In a subsequent memo to students, the university offered a room-and-board refund for students who wished to move out of campus housing and return home. The decree isn’t mandatory, though, and it says nothing of the many students who live in off-campus housing — the same off-campus housing that has reportedly been the locus of transmission. Even Penn, which has held very few in-person classes, has seen a spike in new coronavirus cases — at least 42, according to the school — largely among those who decided to live off campus among friends, despite the mostly-online curriculum. That, again, suggests the fundamental problem is giving students a reason to come back to campus in the first place. Now that Temple has already done so, it might be too late.

On Tuesday, health commissioner Farley did report a glimmer of good news. Cases at Temple appear to be declining, he said, and the outbreak on campus has apparently not yet spread to the surrounding community. While Farley admitted the health department “underestimated the risk of the students that were off campus and out of control of the university, and how quickly we could get an outbreak occurring in that population,” he didn’t go so far as to say the decision to reopen campus was a mistake.

For people who give out grades for a living, Temple administrators haven’t been keen to publicly admit fault, either. In their letter canceling the in-person semester they simply note that “the risks associated with the COVID-19 pandemic are simply too great” to continue a campus experience — despite having decided just a week ago that the risks were not too great at all.

So allow me to do it for all parties involved: This was, in no uncertain terms, a complete and utter failure.