INTERVIEW: Michael Alig on Readjusting to Gay Life After Prison, Dealing With Murderer’s Remorse, and Crying Over Cronuts

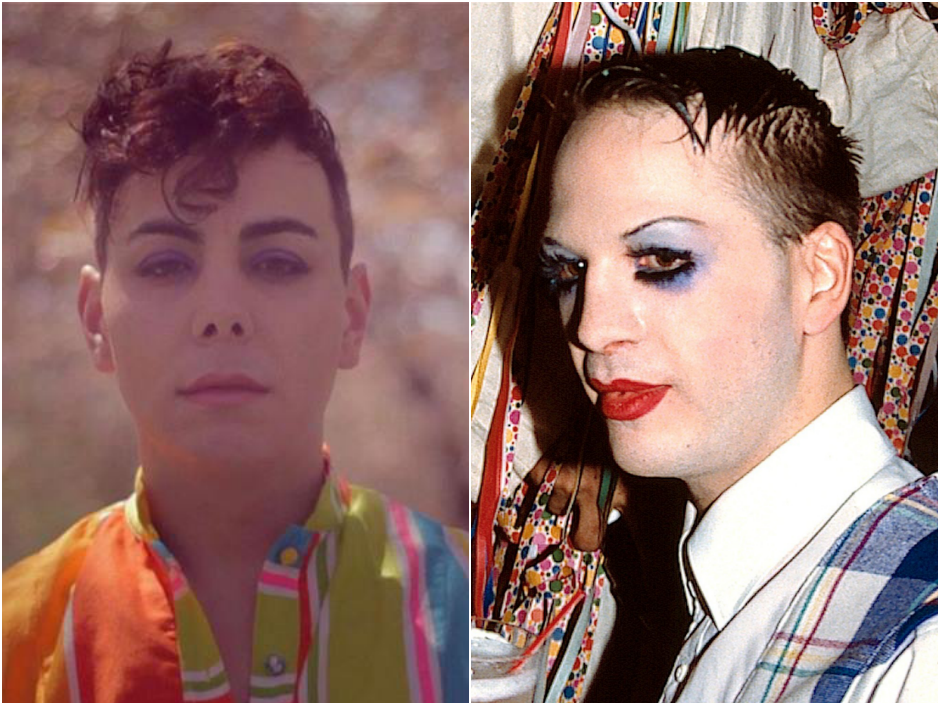

Philly performance artist George Alley (left) interviews original Club Kid Michael Alig (right), who recently finished a 17-year prison term for the murder of Andre “Angel” Melendez.

Original Club Kid Michael Alig made a name for himself in the ’90s for his outrageous parties at the Limelight (that era’s answer to Studio 54) and in precarious, site-specific spaces, like subway trains and Burger King. He and his friends created a rebellious and self-expressive style and attitude that informed global nightlife in the late ’80s and early ’90s. His personal story was immortalized in the book Disco Bloodbath, which was later turned into the successful 2003 movie Party Monster, written by Club Kid co-founder and Alig’s best friend James St. James. Alig was recently released from prison after serving 17 years for manslaughter for the death and dismemberment of Andre “Angel” Melendez, Alig’s friend and drug dealer.

In 1998, still a teenager, I had moved temporarily from Ohio to New York to do an internship with several post-modern dance companies, but I was also hungry to learn more about the art scene outside the theater. After a chance meeting with famed club kid Richie Rich I began to learn more about the Club Kid movement. I was most impressed by its freedom to celebrate gay people not because of their abs or the size of their bank accounts; but because of their inherent fabulousness.

I went into my interview with mixed emotions: On one hand I was excited to meet the man behind a movement that uplifted so many gay people during a time when being gay wasn’t accepted. But then again, well, he committed a savage, unforgivable crime. Despite my apprehensions I bit the bullet and went headfirst into the interview. Here’s how the conversation went:

George Alley: Michael, as you know this interview is for Philadelphia magazine’s LGBT blog, G Philly. Do you have any Philadelphia-oriented stories to share?

Michael Alig: Oh my God, they are not going to want to hear this: We used to do these Club Kid jaunts to cities around the world, and we did go to Philadelphia. When I was writing my book I called everyone I knew who would have gone on the trip to Philly, and no one could remember being there because we were all on so many drugs. The same thing happened with Washington and Boston and Cleveland; nobody could remember.

GA: Part of what Club Kid culture did was sell a lifestyle. These days, social media allows people to put themselves out there like never before. So is there a need for this kind of movement anymore?

MA: That sounds good on paper, but I’ve been sitting in front of my computer all night long answering emails from 17-year-old kids in Kentucky saying things like, “My parents don’t know I’m gay, nobody at school knows that I’m gay. How did you do it? How can you be so self-confident even though you are gay? How do you come out?” It’s just incredible to me that in 2014 there are still pockets of America that are like this. It’s extremely sad. I spend my whole day going back and forth with these people. Some are suicidal, depressed — it’s unbelievable. But to them, they see Party Monster as this generation’s Rocky Horror Picture Show. It’s the first time they are seeing a group of people being creative, different, wild, and self-confident. Having confidence and not being afraid that someone is going to hurt you is very enlightening. It kind of opens up a whole new world that is possible for them.

GA: I did an internship in New York in the late-’90s, and was fascinated by what was left of that culture at the time. It seemed more about glamour than sex, which is what most gay nightlife seems to be about now.

MA: It was purposefully less sexual. One of the things we were was a reaction to the AIDS epidemic. When HIV/AIDS was first identified people just stopped going out. They were terrified. They didn’t know how the disease was contracted, so they stopped hooking up. We had just come out of Studio 54 and Xenon and all these huge nightclubs where people were going out and using cocaine and having sex. All that stopped. When the Club Kids came around we felt like, “Oh my God! We just missed everything!” We missed all the sex, all the decadence, all the fun.” Our reaction was that we were still going to go out, but it’s not going to be the same thing. We aren’t going to go out to be having sex with everybody. We’re going to go out to let our freak flags fly, and dye our hair yellow and paint our nipples purple. We may not look sexual, but we’re going to look fabulous, and that’s a replacement for us.

GA: Why did you return to New York City after your release from prison?

MA: First of all, I had to come back. It’s a stipulation of my parole that you have to live in the community in which you were arrested. But even without that I don’t know where else in America I could survive. I don’t know how to drive a car. I don’t know if the jobs I know how to do exist in other cities. I feel safe here. I can be myself. In fact, I can be more than myself. This is the city where I can be celebrated for being myself instead of bullied or beaten up like in another city.

GA: You’ve been criticized for giving interviews since getting out of jail. Why did you make the decision to go public?

MA: The first night I came out, Ernie Glam, the friend I’m living with, my editor, Esther Haynes, and James St. James took me to a restaurant. I had been in jail for 17 years — in an environment where I could never be myself or let my guard down. I always had to wonder, “Am I gesticulating too much? Am I acting too gay?” I go from a situation like that to being surrounded by great friends who I know are not going to judge me. It was a huge relief. … But there were people there filming and taking pictures and texting Perez Hilton to tell him I was laughing, celebrating and that I obviously didn’t have any remorse. When I went home and saw all this stuff in the media it was just so upsetting that I broke down crying. I told Esther [Haynes] that, “I just don’t know if I can do this. I feel like I have to move to a cabin in the Adirondacks or something. I feel like I’m perpetuating this idea that you can commit an awful crime and come home and get all this media attention and become fabulous.” As ridiculous as that sounds, people were thinking that. We literally made two columns of pros and cons of doing these interviews.

GA: What are some of these other cons to contacting the media?

MA: That Angel’s family would see a lot of this. How is it going to make them feel that the person who killed their [loved one] is now out and in the media?

GA: Pros?

MA: Just looking at the emails I’m getting now. None of these emails from kids in Kentucky think it’s fabulous that I killed somebody. In fact, they all start out with, “We hate the fact that someone had to die, but what happened before that really changed my life.” And that message is so important to get back to if only to start going back to doing good things for people in order to balance out my karma and balance out the devastation I’ve caused. Also, when I was in a jail it took me a long time to come to terms with what we did. I was addicted to heroin when I was arrested, and I continued to use heroin … because I was afraid to face the reality of what I did. It took me many years. I would justify it to myself saying, “I committed this awful crime. No one is ever going to forgive me. There is nothing I can ever do to make up for it. I might as well continue to use drugs and continue escaping like that.”

GA: Why did you decide to stop using drugs?

MA: It wasn’t until March of 2009 when my therapist sat me down to tell me that the reason people continued to say horrible things about me is because I was still using drugs. She said it made me seem insensitive about what I did. That just clicked and made so much sense to me. At that moment I realized it’s not too late; I can turn over a new leaf. I can say I’m not going to do that or be that person anymore even if it kills me. I think it’s a powerful message that it is never too late. I am 48 years old. I’ve committed this awful crime, and yet the minute I stopped using drugs I turned my whole life around.

GA: How were you able to cope with what you did to Angel?

MA: It’s taken a lot of therapy to really come to terms. But it’s still difficult to enjoy things. When I got out, [DJ] Keoki, my ex-boyfriend, came to town to take me clothes shopping. I only had two shirts and two pants when I got out of jail. It was the first time I had been in a department store in 17 years. I was standing in the middle of the store and just started sobbing, thinking I had done this horrible thing. Angel’s family is never going to recover from this. They are going to be devastated for the rest of their lives. There is no closure for them. And here I am in a fabulous department store with somebody buying my Armani underwear, and the whole thing seemed so obscene. I don’t really need any of these things. I don’t need more than two shirts and two pants. It just seems very wrong. I just don’t feel like I’m ready to enjoy anything yet.

GA: I read that you were recently reduced to tears after eating a cronut.

MA: They made it a big joke on Gawker that I was crying while eating a cronut. It sounds funny, but it stemmed from the same things I was feeling in the department store. It tasted so delicious, so satisfying and so sweet. I hadn’t had anything like that in 17 years. I thought of the people I left in prison, what they would have done to have a cronut, which probably cost more than what they would spend in a week on food. It came in this decadent box that probably cost $2. It felt so wrong, so obscene that it became a very emotional experience for me. I don’t know how to explain it, but I guess you could say that I’m having trouble trying to enjoy the finer things in life.