This All Seems Very Familiar, Say Philly Holocaust Survivors

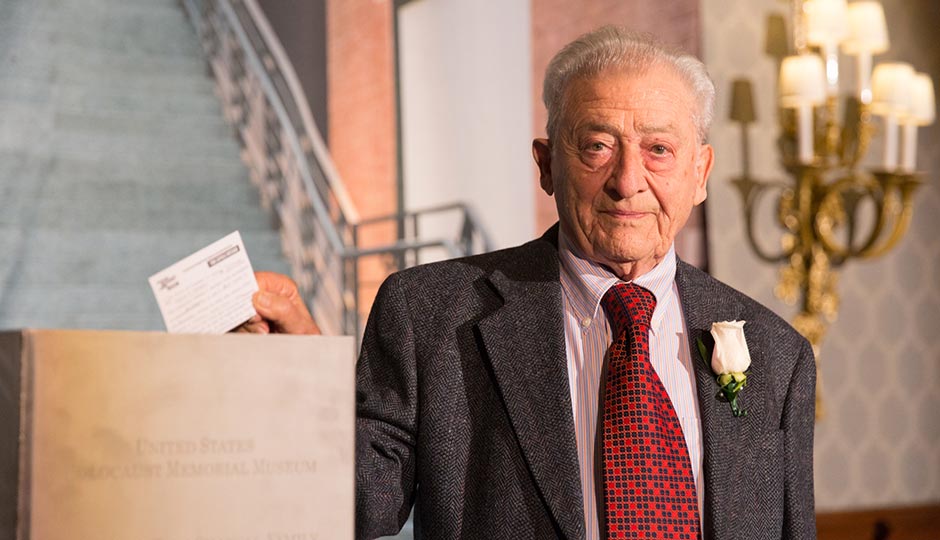

George Sakheim, a Philadelphia-area Holocaust survivor, places a message into a time capsule at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s “What You Do Matters” dinner on Wednesday evening. Photo courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

He is 93 now, old enough to remember gleefully casting a vote for Franklin Roosevelt in the fall of 1944. But George Sakheim has no trouble calling upon memories from even earlier in life, revisiting his childhood with the ease of a man flipping through a photo album.

This one is from 1933. He and his mother were living in Berlin then, the two of them still wading through the grief of his father’s sudden death from a ruptured appendix a few years earlier. Sakheim was in the fourth grade, and on this particular day, he and his classmates were herded to an auditorium for an assembly. A special guest wanted to speak to the children.

And once Adolf Hitler opened his mouth and started discussing his vision for revitalizing Germany — and grousing about the things he believed were holding it back — Sakheim knew something was terribly wrong.

“This was right after he became the chancellor of Germany. The principals were ordered to have the children come to the assembly,” Sakheim said Wednesday morning, his voice as crisp as the fall air. “He ranted and raved about how everything was the fault of the Jews. I went to a primarily Jewish school. It was appalling.”

The angry little man with the cartoonish smudge of a mustache wasn’t just scaring school children. His fiery words were inspiring others to attack Jewish men, women and children who were just going about their lives. Sakheim experienced it firsthand, as he and his school mates were targeted by roving members of the Hitler Youth on the streets of Berlin.

“There was an atmosphere of intimidation. They were showing you that you were disliked and you were not wanted. They were saying get out and go home,” he said. “I had one encounter I remember. I was coming home from school, and some Hitler Youth surrounded me, and they asked, ‘Are you Jewish?'” Sakheim was nine years old; he panicked and blurted out a lie. “I said, ‘I’m half-Jewish,’ so they said, ‘We’re going to beat you up half as much.’ I regret that’s what I said, but I was frightened.”

Sakheim, who now lives in Montgomery County, was among the 70 or so Holocaust survivors who ventured to the Union League last night for a glitzy annual benefit for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The museum is in the midst of a fundraising campaign called “Never Again: What You Do Matters,” and is building a multimillion-dollar center in Maryland to house artifacts and records.

I wondered what some of the survivors thought of the divisive rhetoric that fueled the rise of president-elect Donald Trump, the spate of hate crimes that has dominated the news in the week since he won the 2016 presidential election, and Trump’s decision to name Steve Bannon — the former chairman of Breitbart News, a platform for the alt-right movement that conservative radio host Glenn Beck described as “terrifying” for its white nationalist, antisemitic ethos — his chief strategist.

Sakheim immigrated to the U.S. in 1938, served in the 104th Infantry Division during World War II, and later worked as a translator at the Nuremberg trials. He didn’t hesitate to offer his opinion. “People aren’t going to want to hear it, but as [Trump] talked more and more, he sounded more and more like Hitler,” he said. “There’s that grandiosity, that self-importance, that feeling that he knows everything, that he knows more than the generals.”

Some will howl at such a comment and say it’s unfair to make that comparison, that this is all just sour grapes because Hillary Clinton didn’t win the damned election. Sakheim cautions that it’s too early to know what kind of shape Trump’s administration will take, what kinds of policies it will truly enact. He was encouraged by Trump’s more demure tone during an interview on 60 Minutes. But Sakheim and the ever-dwindling number of Holocaust survivors also lived through the history that you only vaguely paid attention to in school. They know what can happen when hate is allowed to thrive.

MICHEL JERUCHIM’S MEMORIES OF World War II are a little more muddled. He was just a five-year-old boy living in France when his world was upended in July 1942.

“My mother had an appointment with a dentist who somehow or another had been told by a French policemen that they were coming to round up all of the Jews,” he said. “When you have information of that sort, you’re suspicious of how real it is. But by that time, people had been randomly arrested coming out of subways and on street corners, so my parents took it seriously.”

Jeruchim, his parents, and his older brother and sister spent that night at the home of a cleaning lady his mother knew. Thousands of Jews were indeed arrested by French police, under orders from Nazi leaders, in Paris the following day. “My mother knew some merchants in the general area. We were hidden in their back rooms for a time,” he said. “One of those merchants knew a Protestant family that was engaged in some sort of underground [effort] to place people in safe environments. My siblings and I were placed separately in different homes in Normandy.”

He lived with a French Catholic family who treated him as their own until 1945, when Jeruchim’s uncle managed to track him down and reunite him with his brother and sister. They made their way to the U.S. in 1949 — minus their parents, who were unaccounted for. For years, the siblings avoided talking about the ordeal they survived; some nightmares are still terrifying even after they end.

The mystery surrounding their parents’ fate was finally unlocked when Jeruchim’s brother, Simon, conducted research for his 2001 memoir, Hidden in France: A Boy’s Journey Under the Nazi Occupation. The truth was buried in war records, which revealed they’d been captured trying to cross into an unoccupied part of France. “They were taken to Auschwitz,” Jeruchim said. “They were put to death.”

Jeruchim is 79 now. He lives in Philadelphia and continues to work two days a week in the field of communications satellites, putting to good use the electrical engineering PhD he earned at the University of Pennsylvania years ago. He built a good life for himself and his family on this soil after outrunning the Nazi regime’s tendrils.

Imagine, then, what it was like for Jeruchim and other Holocaust survivors to hear Trump state during the presidential race that he opposed allowing Syrian refugees to enter the country, echoing the U.S.’s onetime policy of turning away Jewish refugees during World War II. Think of the shudder that went down their spine as antisemitic language seeped into the race. (Watch as a man at a Trump rally yells “Jew-S-A!” at members of the media, or look at the disturbing messages and images that were sent to Jewish journalists.)

“It has uncomfortable reminiscences,” he said. “The structure of the situation here might not be the same as it was in Germany then, but there are too many similarities. But I’m not going to Canada — yet.”

Jeruchim terms himself “cautiously optimistic” that history won’t be repeated, that the country’s checks and balances would prevent it from tumbling into the unchecked madness that was unleashed on the world during the Third Reich. But he has a simple message for people who didn’t vote for Trump, and worry that their safety and their future is at risk because of their race or religion: “Speak up. Be active. Be vigilant. Don’t just sit back if things turn in the wrong direction. It’s an easy thing to say, not such an easy thing to act upon.”

GEORGE SAKHEIM’S MOTHER KNEW they had to flee Berlin not long after Hitler delivered that speech to the schoolchildren.

Nazi leaders launched an economic boycott of Jewish businesses, and the random attacks on Jews around the city seemed to be increasing. When rumors spread that Jews were going to be forced to give up their passports, Sakheim and his mother packed what belongings they could into a handful of suitcases and bolted to the train station.

Relatives told her to calm down, to wait and see what would happen. “My mother listened to Hitler,” said the retired clinical psychologist. “She told me, ‘He means business. He’s not going to rest until Germany is free of Jews. He’s planning nothing good for us here.’”

They headed first to Murano, Italy, where Sakheim’s parents had spent their honeymoon. Palestine came next, where Sakheim stayed in foster homes while his mother tried to eke out a living as a cab driver and, later, a tour guide. She eventually scraped together enough money to send him — alone — to America to live with an aunt. They stayed in touch through weekly letters, until Sakheim received a telegram from one of his mother’s friends in 1939. She’d been devoured by cancer. When the pain grew too overwhelming, she took her life.

“The other day, I had some people over … and somebody asked, ‘What was the biggest gift your parents ever gave you?’ I’m going to be quiet for a moment, and let you think about that,” he said, his voice lowering to just above a whisper before giving way to a silent pause. “I said, ‘My mother gave me my freedom and my life.’ If she hadn’t gotten us out of Germany, by the time they were doing arrests and deportations, I would have been 18 years old. The right age for them to send me off to the concentration camps.”

He did end up visiting a concentration camp — but as one of the U.S. soldiers who helped liberate Nordhausen, a sub-camp for prisoners who were too sick or weak to work. Photos he took of the atrocities that lurked within the confines of the camp ended up in the Holocaust Museum’s archives.

During the Nuremberg trials, he came face-to-face with Nazi officials who had presided over incomprehensible amounts of human suffering. As a translator, he had a front-row seat for six interrogations of Rudolf Höss, the longtime commandant of Auschwitz. Sakheim remembers Höss turning defiant over the particulars of his confession; he wanted it to be known that 2.5 million Jews were murdered in gas chambers at the camp, but another 500,000 died of starvation, overwork or disease.

Sakheim couldn’t have imagined that 71 years after the Nuremberg trials began, he’d be talking about such darkness and hate in the context of an American presidential election. He and his wife had about 20 friends at their place on Election Night, expecting that they’d watch the country make history as it sent the first woman to the White House. When they went to sleep, the race was still undecided. When they awoke in the Montgomery County retirement community where they now live, they learned that a different kind of history had been made — the first reality TV star had been elected president instead.

“We were shocked. We thought, ‘My God, what’s happened?’” he said.

Friends and relatives reached out, looking for guidance and reassurance, sick with worry that the country was pivoting toward a troublesome path. Sakheim thought good and long about a kernel of wisdom that he could impart. He settled on this: “What I learned from Hitler is the price of freedom is eternal vigilance. Never allow a dictator to take hold and flourish.”

Follow @dgambacorta on Twitter.