What David Bowie Meant to Philly — and What Philly Meant to David Bowie

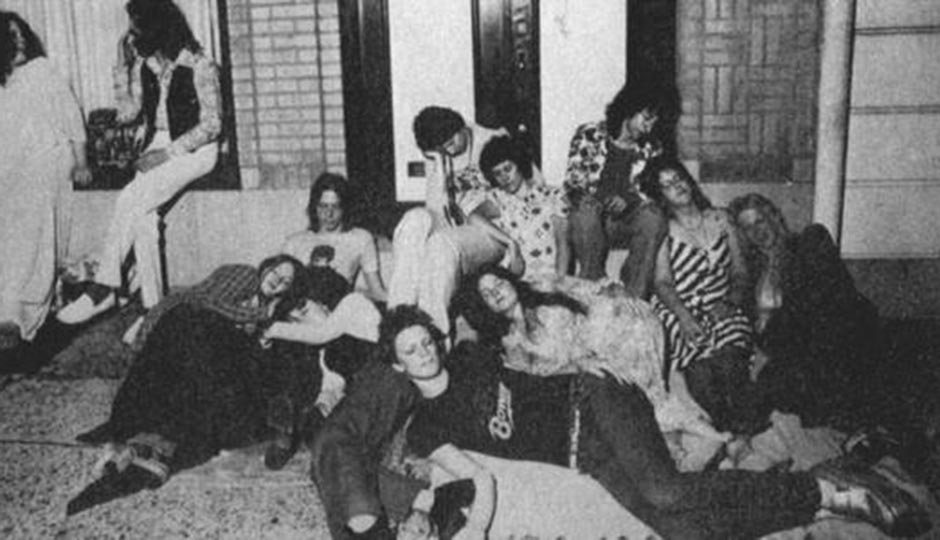

“Bowie kids” in front of Sigma Studios on 12th Street near Race during the recording of Young Americans in 1974.

By 1973, being a “Bowie kid” was an act of individual rebellion complete with its own thriving subcultural support group. The club of trailblazers had already been formed, the glittery dress code had been established and the “outrageousness is next to godliness” ethos was set in stone. Bowie’s 1972 concept album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (and the ensuing U.S. tour and Rolling Stone cover story) had made him an international phenomenon. But he had been recording in England since 1966, and he had been wearing dresses on album covers and publicly declaring his bi- or homosexuality (depending on how the presence of his wife Angie was interpreted) since 1971. Ziggy was simply the most successful packaging of twenty-six-year-old Bowie’s basic themes: alienation, androgyny, other worldliness, production values. And highly theatrical act was the perfect innovation in a rock concert business where demand for showmanship was outpacing supply.

There were Bowie kids all over America and England. In every municipality and suburb, a certain number of people heard Bowie – or his character, Ziggy – speaking to whatever it was that made them feel different: their sexuality, their intellectual aspirations, their disaffection, their rebelliousness. It was mass marketing to those who wanted to be separate from the masses. And since Philadelphia had been among the first American cities to embrace the bisexual Barnum of rock, his cult of personality had grown particularly strong in the Delaware Valley. His fall 1972 shows were such a huge success that when he returned in February of 1972, local promoters were able to sell out seven nights at the Tower Theater, where audiences showed up in outfits that rivaled those worn by Bowie and his band, turning the whole scene into a rock n’ roll performance art piece with a 3,072-member cast. When Bowie then announced his retirement from performance in July of that year, his marketed mystique was solidified.

“He was a genuine guru, a rock star who seemed to hold some secrets in a way that nobody really expected of, say, the Beatles,” recalled Matt Damsker, Philadelphia’s reigning rock critic at the time. “Everyone was so caught up in the shared moment, and Bowie represented somebody so mysterious and so calculatedly brilliant. There was a power to his very best music that suggested a lot of withheld information: it seemed that if you got close to him, he might dispense it to you. He seemed to have a political and metaphysical program in mind. These weren’t stupid kids. They weren’t into Bowie just because they were bored with everything else. They were caught up in something that was pretty broad in its implications.”

Bowie himself would recall of the time, “I never ever thought my songs would help anybody think or know anything. Yet it did seem that at that time there were an awful lot of people who were feeling a similar way. They were starting to feel alienated form society, especially the breakdown of the family as we’d known it in the forties, fifties and especially the sixties, when it really started crumbling. Then, in the seventies, people in my age group felt disinclined to be a part of society. It was really hard to convince oneself that you were a part of society. (The feeling was) here we are, without our family, totally out of our heads, and we don’t know where on earth we are. That was the feeling of the early seventies – nobody knew where they were.”

For Gia, Bowie and adolescence would be interchangeable. Her first haircut since the age of eight – and the first time she ever chose her own hairstyle – was the bushy Bowie cut. It was executed by Nadine at Bonwit Tellers, almost perfectly replicating Bowie’s look on the Pin-Ups cover photograph. “She went from this beautiful long hair to this Bowie hairdo,” Gia’s mother, Kathleen, recalled. “I couldn’t stand it. I avoided seeing her for two weeks.”

Gia’s first experimentations with makeup were definitely not done to make her look more womanly. She and her Aunt Nancy spent an afternoon singing along to Bowie records and perfecting a red lightning bolt from Gia’s hairline to her cheek, like the one on the cover of the just released Aladdin Sane. Among the first clothes Gia bought for herself by herself were red platform boots, a white shirt decorated with back hands that appeared to be wrapped around her upper body, and a feather boa. The red satin jumpsuit had been handmade by her mother as a gesture to befriend this gawky space creature that had once been her adoring daughter.

Even Gia’s handwriting was affected. She began dotting her I’s with circles and signing her notes and letters “Love on Ya!” It was the same way Bowie had scrawled his handwritten liner notes on Pin-Ups.

To her parents, Gia seemed to have been transformed overnight after attending a Bowie show. “She got involved with rock concerts, okay?” her stepfather, Henry Sperr, recalled. “And a bunch of people who went to rock concerts. They weren’t from around here. She got a Bowie haircut and that changed her personality completely. She seemed like a sweet, young little kid before, and then afterward … well, you know it probably had something to do with the drugs. She would be disrespectful, she would be constantly fighting, just over nothing. And she’d be very rebellious. You’d say ‘Be home at ten o’clock,” and she’d come home the next day.”

But that was the way it was for many of the kids caught up in the glitter crowd, some of whom had yet to actually see this creature Davie Bowie perform. They viewed Bowie – not just his records and his image, but the whole scene he was musically documenting – as the doorkeeper to a new world that really was brave.

Joe McDevit was converted at The Tunnel at Cottmann and Bustleton, where teen dances were held on Saturday nights. It was there that the blond, broad-shouldered forklift operator, a seventeen-year-old Catholic school drop-out – was first inspired by a friend with a Bowie-do and a rhinestone shirt.

“Next thing I knew, I shaved my eyebrows off, hit the sewing machine to make glitter clothes and found out about this man in Hialeah, Florida, who made custom platform shoes,” McDevit recalled. “I sent him a tracing of my foot and ordered a pair with eleven-inch heels and eight-inch platforms, navy blue with silver lightning bolts down the side. They came in the mail, a hundred five dollars – I had to work two weeks to pay for them. In a matter of weeks, I went from a normal kid who played baseball at the local field to parading around in full drag. Suddenly, I was bisexual. I had a steady girlfriend, and my boyfriends were all neighborhood kids who played on the baseball team.”

McDevit’s first Bowie concert was also his debut to the Delaware Valley’s David throng as a fanatic to be reckoned with. “We camped out for a week for tickets,” McDevit recalled. “And I had a friend of mind whip up a silver lamé space suit, with a blue lamé jock strap attached to the jacket. I remember waiting for Bowie to come on stage for my entrance. I felt so special. He was on stage singing and I walked down the aisle. They put the spotlight on my and I started throwing kisses.” On that night, Joe McDevit became “Joey Bowie.”

For others, the evolution was less theatrical. “The way I remember it,” recalled one friend of Gia’s, “I was a little kid watching The Brady Bunch one day and the next day I was in a bar with a Quaalude, even though I was only fourteen. It was just a very crazy time to be in high school. I remember staying out all night on a weeknight and then hailing a cab to take me straight to school from the clubs.”

The Bowie crowd at Lincoln, though small, quickly developed its own hierarchy and heroes. Although it was mostly girls – a male took a much higher risk coming to school wearing makeup – the leader of the pack was Ronnie Johnson (a pseudonym), a sixteen-year-old dead ringer for Bowie. Ronnie wasn’t so much the ultimate Bowie fanatic. Ronnie Johnson was David Bowie – or as close as you could get and still have a locker at Lincoln. He designed and sewed his own Bowie-inspired-clothes: did his own embroidery, affixed his own sequins. He combed the high-fashion magazines for the latest tends in hair, makeup and clothing. He understood that Bowie’s outfits, extraterrestrial to girls who shopped in malls, were merely the most futuristic designs of top European and Oriental dressmakers.

Ronnie and Gia immediately hit it off. When they saw each other, Gia made it a point to bite Ronnie, as a sign of playfully outrageous affection. Besides Bowie, they shared the bond of emotional, broken homes. “His father left the family when he was like three,” recalled one of Johnson’s high school friends. “And his mother was this wild woman, a waitress at the diner.”

And Ronnie and Gia had something else in common. The Bowie kids did a lot of sexual posturing. Bowie was bisexual so, at least in theory, they were, too: they cross-dressed, they cross-flirted. In practice, however, few of them did in private what they claimed to do in public. And some of them didn’t do anything at all. All of which made life much more confusing for people like Gia and Ronnie, who, deep inside, suspected that they really were gay, and wanted to do something about it.

WHEN THE ANNOUNCEMENT came over WMMR-FM, word spread through the Bowie community like a batch of bad hair dye. The T. Rex show scheduled for the Tower Theater was canceled. Ticket holders could get a refund at the box office or, for an extra dollar could trade in the tickets for the same seats to see Davie Bowie, who was coming out of retirement to support a new record.

Diamond Dogs was to be the turning point in Bowie’s career. Renaming 1974 “The Year of the Diamond Dogs” was part of the campaign by Bowie’s management to explain his formative year away from performing and to sell his new image. Bowie wasn’t going to be Ziggy Stardust anymore. He was going to throw a wrench into the time-honored machinery of pop stardom by splitting with his past image and repositioning himself as a musical chameleon — a pretentious changeling with no real identity beyond the parts he played and the costumes he wore. The futuristic hell portrayed in the lyrics and on the album cover suggested a reason for throwing Ziggy to the dogs: the decadent life of rock stardom had destroyed his sensibilities. Luckily, the album Diamond Dogs had a few catchy tunes among the dystopian posturing: “Rebel, Rebel” was Bowie’s most radio-ready hit yet.

Bowie was now big enough to play to sold-out stadiums: under normal circumstances, he would have been expected to play the cavernous Spectrum. But as a gesture to his Philadelphia fans, he had instead decided to play the smaller Tower Theater for as many nights as he could sell out.

The Bowie fans camped out for several days for tickets. In the year since Bowie’s last appearance, there had been many converts: the outdoor slumber party became a sort of family reunion for people who never knew they were related. It was also, for the uninitiated, a major rite of passage. The older fans tried to scare off the kids with a special harassment technique. “They called it ‘reading you for filth,’” recalled one ticket camper. “We’d protect the younger kids in line. They would torment them, dare them to do drugs, tease them with lots of sexual innuendo.” Another ticket-line veteran remembered a Bowie-nut removing her in-use tampon and throwing it at one of the kids. “I think they had seen too many John Waters movies,” he laughed.

The night of the second show, Gia’s friend Karen Karuza put on the outfit she had planning for months: the tightest jeans she could find, a glitter tube top and silver, glittery, four-inch high platform shoes. She knew she was bucking the Bowie dress code, which had been established when David stunned the first-night audience with an entirely new look. Instead of glitter clothes, he appeared in baggy pleated trousers, suspenders, a white cotton shirt and black ballet shoes. His hair was slicked straight back. Karen heard that during opening night intermission – a theater convention rarely used at rock concerts – the scene in the bathrooms was frantic. Some glitter boys and girls hurriedly altered their outfits, wetting down their spiked hair, rubbing off their makeup lightning bolts and rolling down their pants legs.

Gia, of course, had been on top of the new Bowie look for months, since Diamond Dogs was originally released. She went to the show in what had become her new uniform: a white T-shirt, patch-pocket fatigues, heavy boots and a red beret from the I. Goldberg Army-Navy store. And no makeup.

Passing through the crush of weird looking people outside the Tower, who had managed to turn the blue-collar Upper Darby neighborhood into a Bosch painting, Gia and Karen went in to take their seats. But the ushers said there was a problem. Extra sound equipment had been brought in at the last minute and a mixing board now sat where they were supposed to: fans would later find out that the shows were being taped for a double live album. As a way of apologizing of the inconvenience, management had arranged for the displaced fans to sit in the orchestra pit. Down front. If they had ever needed a sign that their love of Bowie was divinely ordained, this was it.

As the lights went down, all eyes were directed to the stage, where Bowie appeared with two male dancers on leashes, dancing on all fours. He sang “1984” while spotlights revealed the show’s elaborate set, a Broadway-on-acid display that redefined the parameters of rock spectacle. In the front rows, the Bowie kids began the frenzied process of getting David’s attention: waving signs, flashing breasts, tossing flowers and notes onstage, or just staring intently at his face, hoping to catch his eye when he scanned the throng. Ownership of those passing glances was hotly contested – glitter girls would argue between songs, “He looked at me,” “No, he looked at me” – and if David actually read your sign out loud or acknowledged your offering, status was immediately conferred.

As the second half of the show came to a close, Bowie shocked the crowd by doing an encore, something he generally avoided: the hardcore Bowie fans took it as a personal gift, something they had willed by their own enthusiasm. About halfway through the song, Gia grabbed Karen’s hand and dragged her out the side exit of the theater and around back. As Bowie shuffled out the stage door and slid into his waiting limo, Gia vaulted over the yellow police barricade and leaped onto the hood of the car, face against the windshield. Bowie slunk down into the back seat as Karen waved to him from the sidelines. And when it became clear that the driver wasn’t going to stop, Gia rolled off the hood, victoriously brushing off her hands. “Geez, we just wanted to say hi,” she said.

IT WAS THE BEGINNING of a week of Bowie madness, with Gia meeting and making a reputation for herself among the older Bowie kids like Marla Fuzz, Fat Pat, Purple and, of course, Joey Bowie. The hardcore fans found out what rooms the Bowie entourage had commandeered in the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, and they staked out his floor. They called the Bellevue front desk repeatedly trying to get connected to his suite. They set up positions in the hotel’s grand lobby, and chatted up roadies, sound technicians, or anyone who looked vaguely rock ‘n’ roll, in the hopes of being invited up. One group even followed Bowie’s dry cleaning up in the elevator.

Gia was one of the few Bowie kids whose mother sometimes tagged along. She even attended one of the latter Tower shows. “I tried to understand why Gia liked Bowie so much,” Kathleen recalled. “So I ended up going to some concerts with her and learned to appreciate Bowie as an artist, a real talent. Gia was tickled to death. I went to the Tower Theater and you could get high just from being in there. I couldn’t believe an establishment could have a smell that strong and get away with it. I tried to sit down and talk to some of her Bowie friends, who absolutely drove Henry crazy. I always got along great with her friends. They thought I was really neat because I really tried to understand them.”

“The mother would come to concerts,” recalled Ronnie Johnson. “It was so ridiculous. Gia would be high and the mother there thinking she was protecting her daughter.”

“I didn’t find it strange for her mother to do that,” said Karen Karuza. “I had another friend whose mother came to all the concerts. In fact, I remember Gia telling me about one time her mother came back to Bowie’s hotel with her after the concert. She was saying, ‘Here’s my mom with her blond hair and her white Caddie and her big fur coat and she’s talking to Jimmy James, Bowie’s bodyguard.’”

One afternoon, Gia actually managed to wedge herself into Bowie’s elevator before the door closed. Realizing he’d been caught, he leaned against the wood-paneled elevator wall and closed his eyes. Gia just stood there and stared at him, too stunned to act. She finally managed to say hello, introduce herself and even shake his hand before he got off. She was left dumbfounded. A few days later, she wrote about it in a letter to Ellen Moon – who spent summers with her parents in the Poconos.

“Howdy Ellen … I got to shake hands with Bowie Friday night because me and my mummy followed his limo. His arms feel really nice. He’s one nice piece of ass …. I’ve done a couple 7-14s (Quaaludes). I’ll try to get you two. They make me too horny and tired. There’s a lot of reds going around here… My mother got her hair cut into a Bowie. Ha! Ha! I think she’s a bit nuts. When you do come back to old Philadelphia if you want to you can take some coke! Take care… see you later alligator… Bowie is the most beautiful person! Don’t cry like me, Love, Gia.”

In the top margin of the letter, Gia explained, “Don’t write me cause I might be living somewhere else.”

BUT THE SEMINAL EVENT in Bowie fandom was still to come, a moment in pop music history that would make Gia and her friends the envy of rock fans the world over. Several weeks after the Tower concerts, in mid-August, Bowie returned to Philadelphia to make a record wit hit-making sensations Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, whose Philadelphia International level was suddenly the second coming of Motown. Mixing smooth rhythms and lush orchestrations at the local Sigma Sound Studio, the company had been cranking out hit after hit, each one breaking first on black radio and then crossing over to white audiences. Bowie’s celebrity at this point was still far grander than his album sales: he hoped Gamble and Huff could help him make a record that would appeal to young Americans.

His extended visit made the Bowie kids feel they had been somehow chosen for a divine mission. A core group camped out in front of the studio each evening while Bowie worked through the night, and waited in front of his hotel all day while he slept. During the two weeks Bowie was in town, Gia and the other apostles didn’t even go to the Jersey Shore, where Philadelphians usually migrated each summer. Several of the older fans were fired from their jobs because of the time spent waiting. They grew so chummy with Bowie’s entourage that one night they convinced his limo driver to let them pick David’s hairs off the car’s backseat and empty the cigarette butts from his ashtrays.

Their perseverance did not go unrewarded. As the week wore on, Bowie began stopping to chat with the fans outside the hotel and the studio. “I introduced Gia to David at Sigma,” recalled Toni O’Connor (a pseudonym), who, as an eighteen-year-old from Chestnut Hill, had only started coming to Bowie concerts the month before, but was making up for lost groupie time. “I had met him at a big party at his hotel after the show a few weeks before. He fell in love with me instantly.”

Then, at five in the morning after the final session, Bowie took the unprecedented step of inviting the ten fans who remained into the studio. They were played rough mixes of the record, they danced with Bowie and personally offered him their ecstatic comments about Young Americans. They even had their exploits detailed in the newspaper. Bowie had made sure that a reporter was in attendance before “spontaneously” inviting the kids in.

The story made the front page of the Evening Bulletin, accompanied by a picture of Toni O’Connor that caused her to skyrocket to subcultural fame. Then the writer capitalized on the rock world scoop by selling a version of his story to Rolling Stone. Within a few weeks, every rock fan in the English-speaking world knew that the sycophancy envelope had been pushed by triumphant Philly fanatics. But, for once, Gia was left to join those non-insiders kicking themselves with jealously: she had grown inpatient during the last hours of the Bowie vigil, and left before the grand finale.

©1993 by Stephen Fried; used by permission. Thing of Beauty: The Tragedy of Supermodel Gia is available in paperback from Amazon.