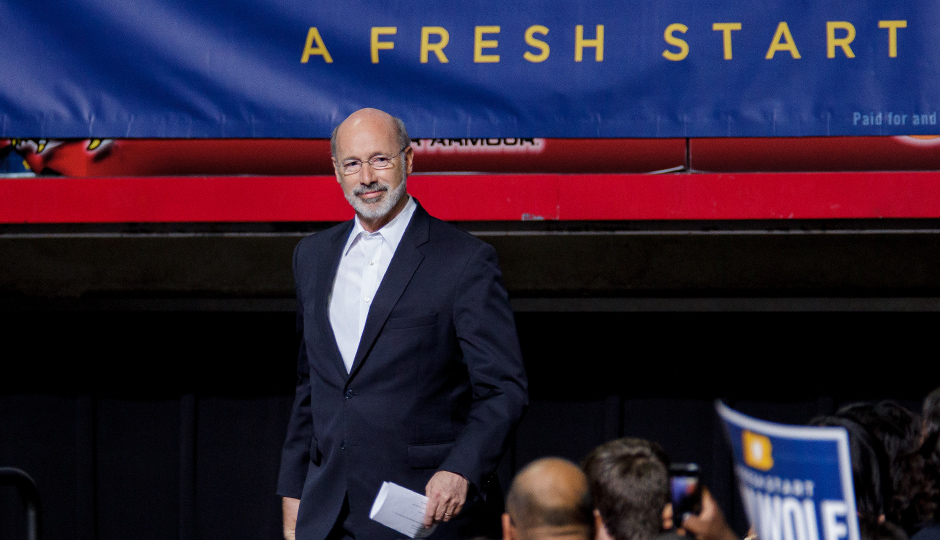

What Governor Tom Wolf Means for Philadelphia

Photo | Jeff Fusco

Four years of Tom Corbett have, to put it mildly, been rough on Philadelphia. Chaos in the state-managed and largely state-funded school district. Cuts to social services that Philly’s high-poverty population rely on heavily. A general sense that the city’s worries and challenges were not a priority for a Republican governor from the other side of the state.

Well, Corbett is finished, in significant part because 88 percent of Philly voters cast their ballots for Wolf.

So how will the city fare with Governor Tom Wolf, a progressive Democrat, running Pennsylvania?

Better, probably, but not nearly as well as many imagine.

Yes, Wolf’s priorities and politics are far more closely aligned with those of most Philadelphia voters. And yes, any Democrat elected statewide owes Philadelphians a debt. But Wolf, unlike Corbett, is looking at a General Assembly dominated by the opposing party. The Republican House is thoroughly controlled by party’s right flank, and the GOP Senate Caucus is in the midst of a high stakes power struggle between the moderate elements that control it now, and more conservative members. Indeed, there are growing whispers that Republican Senate Majority Leader Dominic Pileggi, a key Philadelphia ally in Harrisburg, could be in trouble.

All of which will make Wolf’s job extraordinarily difficult, and is likely to limit the upside a Democratic governor might have represented for Philadelphia in the past.

Let’s zoom in on three areas of huge concern for city residents: education, social services and energy-related economic development.

Education

Wolf is getting Corbett’s keys to the governor’s mansion, and he’s also inheriting Corbett’s School Reform Commission appointees, which is a little awkward, given Wolf’s frequent calls to abolish the SRC.

Can he do it? Can Wolf restore local control of city schools?

Probably not anytime soon. Only the SRC itself or the state legislature can dismantle the commission. Neither seems likely. And I wonder just how high a priority it is for Wolf to restore local control of city schools, which could well give Harrisburg legislators even less of a reason to provide adequate funding.

Will Wolf ask the SRC’s gubernatorial appointees to resign (the gov appoints three of the five, the mayor picks the other two)? Maybe, but it’s unlikely to work. Love it or hate it, this SRC is convinced it is acting in the best interest of city kids, and it’s hard to see the likes of Bill Green, Farah Jimenez and Feather Houstoun bowing out simply because Wolf asks them to. State-appointed SRC board members are appointed to five-year terms. The entire point of those lengthy terms is to give SRC members genuine independence from the governor’s office.

Wolf could, however, use the bully pulpit to isolate the SRC. He could put a lot of pressure on the SRC to negotiate a new contract with city teachers, instead of trying to impose terms. He could instruct the Department of Education to look at the district more skeptically. I don’t think it’s in Wolf’s makeup to do so, but it’s possible.

Even if Wolf were inclined to intervene in the legal battles between the SRC and the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, there might not be all that much he could do. The Commonwealth Court has taken the case and is considering it on an accelerated timeline. There might well be a ruling before Wolf is sworn in. And even if there isn’t, the state is not a party to the case, and it’s not clear what if anything the state’s Office of General Counsel could do at Wolf’s instruction to impact the case.

How about funding? Wolf’s platform called for expanding statewide funding of schools by as much as 56 percent, which has approximately zero chance of happening. Indeed, any significant new statewide schools revenue is likely to be a major challenge, given Republican sentiments on new spending.

Wolf might have better luck hammering out a new school funding formula. Statehouse Republicans are open to talking about a new formula, and the hope in Philly is that an equitable formula would give the city a somewhat larger share of state education dollars than it gets right now. But that all depends on the formula, and getting a formula that is politically plausible is particularly challenging without new revenue to make the medicine go down a bit easier for those districts that come out as long-term losers with the new formula.

One relatively cheap way for the state to address Philly’s schools crisis without opening up a statewide can of education worms would be restore what’s called the “charter school reimbursement line,” which refunded districts about 25 percent of their charter school costs. Corbett eliminated that funding, which was a huge blow to Philly, given the abundance of charter schools in the city. Advocates want Wolf to put the line back in. That seems like a longshot at best, given that it requires the approval of a General Assembly unlikely to do Philadelphia any special favors.

Long story short: Electing Wolf isn’t an overnight cure for any of the problems ailing city schools.

Social Services

Corbett borrowed a lot of pages from the contemporary GOP governor playbook in the last four years. He introduced asset testing for food stamps. He balked at a full adoption of Obamacare. And in the rare instances where Corbett expanded social services — like enhanced funding for pre-K — Philly got the short end (the state capped the pre-K expansion at 80 seats per district, which kind of sucks for a city with a district that is exponentially larger than typical state districts).

Social services are important everywhere, of course, but a high-poverty city like Philly obviously has a much greater need for quality social services than, say, Chester County. Wolf is unlikely to secure any real expansion of social service spending, given the dynamics in the General Assembly. But he can, at the administrative level, eliminate the food stamp asset test (which advocates have said discouraged eligible families from applying for food stamps), switch the state to a full Medicaid expansion, and generally purge the state’s Department of Public Welfare of a mindset that sought, in many cases, to deny benefits, instead of deliver them. That works to Philly’s advantage.

Energy hub

Over the next four to eight years, Wolf could end up playing an enormous role in deciding whether or not Philadelphia evolves into an energy hub. Tom Corbett just may have been the most extraction-friendly governor in the nation. Wolf, meanwhile, has called for a 5% Marcellus Shale extraction tax, and he’s unlikely to be quite as blase on the environmental impacts as Corbett was. The state can make it very challenging to build the pipelines and other infrastructure needed to make Philadelphia into an energy hub. Energy executives are nervous.

Wolf temporarily silenced the progressive crowd at his victory speech last night with a few lines advocating not just for the extraction of natural gas, but Pennsylvania’s other resources. “Everyone’s talking about gas, but we also have coal,” he said. “We’ve got to make sure coal is relevant in this new age we’re entering into. We have to make sure we take advantage of our fresh water resources, our timber and our open space.”

Still, there’s sure to be a gap between the Corbett and Wolf approaches to energy, with potentially far-reaching implications for the city.

Update: This story was updated to correct an error misstating the length of gubernatorial appointments to the School Reform Commission.

Follow @pkerkstra on Twitter.