How To Win Elections Without the Democratic Machine

(Editor’s Note: This is an op-ed from Andrew Stober, an independent candidate in the 2015 general election.)

This year, I ran for City Council at-large as an independent, giving voters the opportunity to elect a progressive candidate who wasn’t indebted to a political machine. I was ultimately unsuccessful. But, as I emphasized throughout the race, I was running to blaze a trail for other independent candidates to follow. In that spirit, here are a few key lessons that I learned in the campaign.

And who knows? Maybe I’ll do it again.

1. Know what your obstacles are.

We started the election with a lot of challenges. The race for City Council at-large is what political scientists call a low-information, low-salience race. That means voters don’t know the candidates and don’t particularly care about the election. In this already challenging environment, we asked voters to understand the nuances of the Philadelphia’s political system, which ensures that two City Council at-large seats are not held by the majority party. To put a finer point on it, we asked voters to change 60 years of voting behavior.

The party machines turned out predictably strong, straight-ticket votes, rewarding Democratic candidates with a minimum of 113,700 votes and Republican candidates with 19,800 votes. Our campaign earned 16,301 votes, and a winning position in 16 wards across the city. When you add these results to the impressive efforts of Green Party candidate Kristin Combs and independent candidate Sheila Armstrong, the vote total for progressive-minded independent campaigns tops 33,000. That is more than five times the number of votes received by the most successful independent candidates for City Council in past elections.

2. Start early.

Before I jumped into the race, I worked in Mayor Michael Nutter’s Office of Transportation and Utilities. While my experience working for the city was an advantage in many ways, it also delayed the launch of the campaign, as the law barred me from running for office while collecting a city paycheck. Starting a campaign earlier would allow an independent candidate more time to raise money, earn endorsements, build relationships and educate voters.

The late submission date for nominating paperwork was also a major factor in my race. Independent candidates are required to file their paperwork less than three months before the general election. Many of my eventual supporters waited to make sure that I was on ballot before they gave me their full support. This narrow window made it difficult to maximize the momentum of endorsements and contributions from my most prominent allies.

3. Raise money. Lots of money.

In just four and half months, my campaign raised more than $137,000 from 475 donors. Following an expensive, competitive Democratic primary in which six progressive challengers collectively raised nearly $1.5 million, $137,000 was probably close to the maximum that an independent progressive could have raised.

In a future campaign, more donors would likely direct their resources to an independent candidate who declared early and could unseat conservative incumbents with track records of voting against schools, working people and the LGBT community. Additionally, raising money over the summer is difficult because people pay little attention politics after the primary election, and vacations make it difficult to be in contact with donors.

4. Get endorsements. Lots of endorsements.

I had the good fortune of earning a few high-profile endorsements in the weeks before the election, including from Nutter, former Gov. Ed Rendell, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers and the Fraternal Order of Police.

The summer proved to be a difficult time to get the attention of the organizations most likely to endorse an independent progressive, however. Many influential groups, including the AFL-CIO, run their endorsement processes in the spring. Being considered during that cycle could give an important leg up to an independent. Combs can credit her strong results, at least in part, to having spent the spring earning such endorsements, including from the 10,000 members of Philadelphia’s largest public sector union, AFSCME District Council 33.

5. Build relationships.

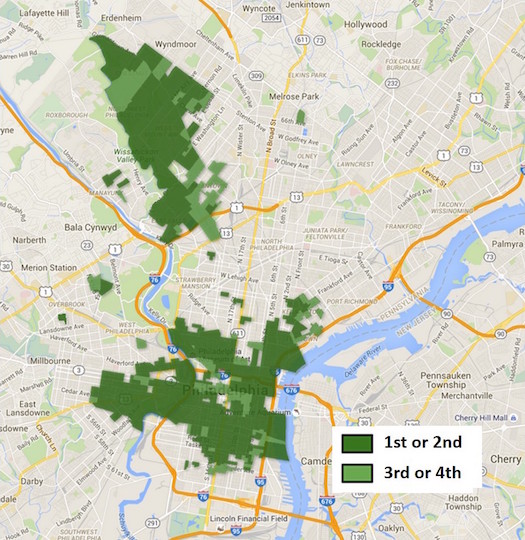

A credible candidate will come to the race with an existing base, or a profile that will attract a base. My campaign had the latter, and the map below shows the unsurprising result that my profile attracted large numbers of votes in Center City, South Philly, West Philly, Chestnut Hill and West Mt. Airy. For an independent candidate to win, they must connect with community leaders and organizations outside of these neighborhoods that are just as hungry for new voices on City Council.

The map below also shows that I had a strong performance in pockets of North Philly and East Falls. In each of those areas, I built relationships that delivered strong returns on Election Day. More time to build similar relationships in other areas throughout the city would make a significant difference on a future Election Day.

Map by Michael Hollander

5. Educate voters.

Hands down, this is the biggest challenge for an independent candidate. Not only do you have to introduce yourself to voters and build name recognition, but you also have to explain why and how to vote for you. This is an enormous effort in a low-turnout, low-salience race. It is made even more difficult by the fact that independent progressives have to explain to lifelong Democratic voters that by voting for them, instead of Democrat, they’ll actually help create a government that better reflects their values.

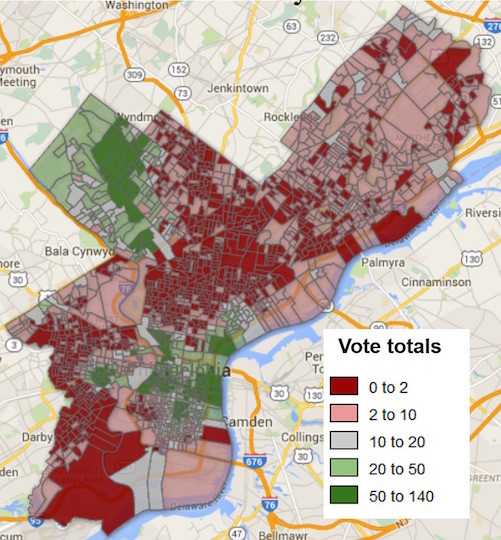

The map below shows the large number of divisions where my campaign received 10 votes or less. This could only be overcome by more and better voter education.

Map by Michael Hollander

Informing voters is about the quality and reach of message. Reach is all about money. Our single mailer targeted super-voting households in the river wards, Center City, South Philly, parts of West Philly, and swaths of Northwest Philly. Our digital ad, which ran before videos on websites like YouTube and CNN, was a biographical spot, not a voter education spot. It made more than 1.25 million impressions on about 60,000 Democratic, independent and “weak” Republican super-voters citywide.

My digital ad overlapped too much with my print mail recipients, and may have missed an opportunity to educate voters. A similar campaign with triple my funding would be highly competitive if for no other reason than it could reach that many more voters.

6. Use the information gathered in my race.

My campaign shook things up. I may be the only candidate in the city’s history who has had ward leaders turn down offers of financial support on Election Day. While many Democratic committee people publicly and privately encouraged neighbors to vote for me, they also told me that ward leaders explicitly told them not to support non-Democrats for the first time ever.

But Democrats need not fear: The election results showed, yet again, that candidates for the minority Council seats are not a threat to Democrats. This year, the gap between the least successful Democratic candidate and the most successful minority party candidate was more than 102,000 votes. The only thing threatening about an progressive independent to the Democratic Party is their potential to disrupt backroom deals with the Philadelphia GOP.

7. Be positive.

Winning a City Council at-large race is all about name recognition. Going negative on Council members or the office itself does not help the challenger. Rather, it discourages voting and boosts name identification for the incumbents. Supporters of City Councilwoman-elect Helen Gym’s campaign were positive and focused solely on her. The Philadelphia Federation of Teachers also proved to be a powerful ally for Gym: The union had an adept understanding of the dynamics of the at-large race, putting considerable financial and field resources behind just her. She carried that momentum through to the general election, and in the end, she ended up receiving more votes than any other at-large candidate.