Franklin Institute’s Virtual Reality Exhibit Is Much More Than an Exhibit

Photo by Fabiola Cineas

On Tuesday evening, I traveled to Tanzania and spent some time at a refugee camp. There, I experienced what it was like to fall asleep in a tent shrouded by a thin blue net, my only protection against malaria-carrying mosquitos. I shared the tent with a mom and her seven children for about 15 minutes.

I couldn’t exactly feel the looming threat of malaria, and the darkness of the night on the campgrounds didn’t startle me too much—I knew I was standing in the lobby of the Franklin Institute the entire time, and I couldn’t ignore the weight of the virtual reality goggles strapped to my head.

But what I did feel in those 15 minutes was connect to the family, their deep sense of hope and desperate quest to stay alive.

A couple of feet away from me were Philadelphians performing brain surgery. Some were deep diving into a far-off ocean or the galaxy; others were at a Drexel men’s soccer match, with a 360 degree view.

The opening night of the Franklin Institute’s Virtual Reality exhibit brought together people who had an interest in something that still seems niche —but it’s not. The sold-out event packed in about 1,000 people, Urban Outfitters is selling a VR headset for $32, and the industry is predicted to balloon to an $80 billion market by 2025 with hardware and software developments that go far beyond the gaming world, the biggest winner in the sector so far. (Another source shamelessly predicts the market will hit $120 billion by 2020.) VR gaming sales in 2015 alone amassed $660 million.

The Franklin Institute has positioned itself as one of the region’s and country’s virtual reality beacons, and this tilt to the unknown makes a lot of sense.

The Institute has launched a mobile app to house a library of science-themed virtual reality content and it’s opened the “holodeck,” a virtual reality demonstration and lab space on the museum’s grounds. With these resources, visitors can more deeply connect to some of the museum’s core exhibits like The Giant Heart, Your Brain and Space Command, by dropping down into a room of doctors preparing for heart surgery or by actually landing inside a computerized human brain.

“What we hoped to do with the different demonstrations tonight was show the different practical applications of virtual reality,” said Susan Poulton, the Institute’s chief digital officer who has developed the exhibit with Larry Dubinski, the Franklin Institute’s president and CEO. “It’s really about connecting our visitors to multi-dimensional storytelling and immersive experiences.”

Students and professors from medical schools at Temple, Penn and Thomas Jefferson were present, showcasing their VR medical training software and the data they’ve been able to collect from watching users enter the virtual world.

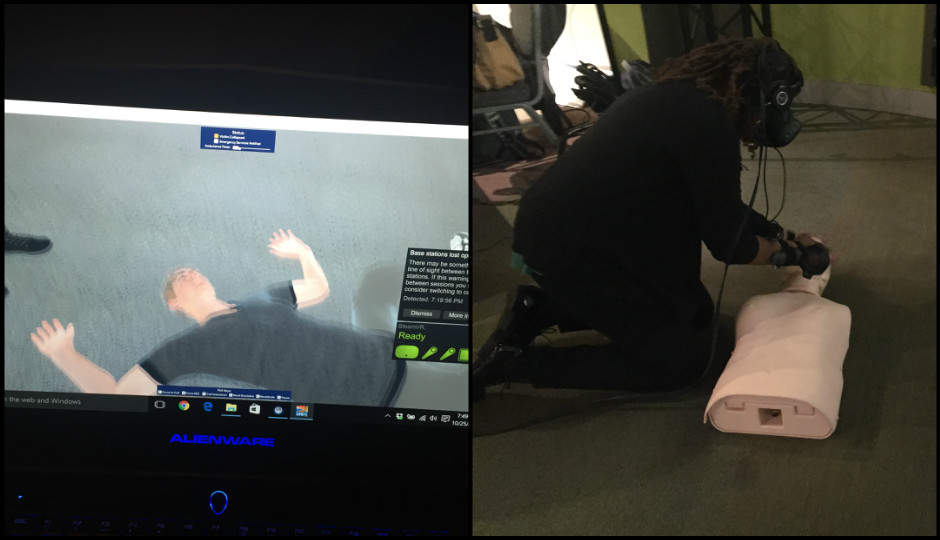

“We want to see if we can improve emergency preparedness training with our system,” said George Lin, who works under the guidance of Marion Leary at the Pereleman School of Medicine’s Center for Resuscitation Science. The point of their research is to observe what people do if someone collapses right in front of them. Do they walk away? Do they scream for help? Or do they get on their knees and perform CPR?

Photos by Fabiola Cineas

“With this tech, we’re hoping to get more people doing CPR and ultimately a higher survival rate for those who might experience cardiac arrest,” said Lin.

Some other fields with current applications of VR include retail, entertainment and hospitality. Shoppers can take an immersive store tour; sports fans can attend a match in their living room and music enthusiasts can attend a concert. Spas are whisking people away to paradise with VR.

Another area is what the New York Times calls the “empathy engine.” I landed in Tanzania through the United Nations Foundation’s Nothing But Nets global campaign effort, which uses virtual reality to share knowledge about malaria prevention.

“Nonprofits are seeing that engagement and donations rise when people experience their causes in VR,” Poulton said. “So if this can inspire people to care about these issues and donate, we want to know whether we can inspire you to do something for science.”

I hung on to Poulton’s every word Tuesday evening because her excitement and optimism for the project was so genuine and her path to leading the museum’s digital efforts was nontraditional.

“I’m new to museums. I’m a big digital native.” she told me, “I got the privilege to be a part of the birth of the internet. I worked for Steve Case when he started AOL.”

Adding, “Back then, we were making it up as we went along. There were no rules. And right now, it feels like that time.”

The museum had to get past fears to really enter a space that’s still largely undefined, Poulton said.

“Part of doing VR was a transformation of us at the institute. Museums are hesitant to invest in bleeding-edge technology because they want to wait and see how it plays out elsewhere,” she said. “At the institute, we’re actually going to be a part of the experiment.”

But as I made my way way around the showcase, I still couldn’t help but wonder: What if the museum’s attempt to get people interested in science through VR is a total wash?

“That’s one of the more interesting things with this,” said Poulton. “It may only have a year of life at the institute, and we have to be ok with that.”

But the museum has done a lot to prove that it’s in this space to stay.

They have plans to regularly add content to the app’s library and are looking to stay on top of hardware developments. They’d like to eventually bring in the HoloLens, Microsoft’s VR system that is actually available for demo in Philadelphia’s Microsoft Reactor, or the highly anticipated technology from Magic Leap, whenever it hits the market. The holodeck is currently equipped with Oculus Rift and HTC’s Vive, expensive systems that definitely aren’t in the average home. Augmented reality (think Pokémon Go) and mixed reality (a combination of the real, virtual and augmented worlds) were also thrown around in conversation throughout the night.

“We are right at the beginning of discovering where this technology can go. The headsets are really the first step,” Poulton said.

“It’s about learning the fundamentals so that you’re ahead of the game and ready for when the next experience comes out.”

Follow @fabiolacineas on Twitter.