Philadelphia + a Pipeline (or Two) = America’s Next Energy Hub

The PES refinery in South Philly. Photograph by Jonathan Barkat

About 1,400 miles from Philadelphia, at the northern edge of the Louisiana bayou, lies a spaghetti junction of steel tubing called Henry Hub, where 13 natural-gas pipelines converge amid farmland and little else. The nearest town, Erath, population 2,100, is about four miles away.

Gas from all over the country flows through the Henry Hub. Even gas extracted from drill pads just 100 miles or so from Philadelphia — gas sucked from the almost unfathomably rich reserves of the Marcellus Shale — is often pumped to distant Louisiana before making the long, and expensive, return trip to homes and businesses in Philadelphia.

Apart from Henry Hub, this section of Louisiana is probably best known for the bizarre cautionary tale of extraction run amok at nearby Lake Peigneur. There, in 1980, an oil crew dug too deep, puncturing a hole in a working salt mine that lay beneath the lake bed. As water rushed into the mine, a swirling vortex formed on the lake surface, swallowing two drilling platforms and 11 barges. The suction reversed the flow of a canal leading to the Gulf of Mexico, and within a few hours, a shallow fishing hole had turned into a 1,300-foot-deep saltwater lake.

Undaunted by that catastrophe, AGL Resources later converted two of the (unflooded) caverns beneath the lake into natural-gas storage facilities, and now aims to double that capacity. It’s a proposition that would be unthinkable almost anywhere in the country, but this is the Gulf Coast, where the extraction, processing and transport of natural resources like oil and gas form the foundation of the economy and employ a massive chunk of the workforce. For cities like Houston and Dallas, and for countless smaller Gulf Coast communities like Erath, fossil fuels — and the prosperity and unfortunate side effects they tend to create — are an indelible part of life.

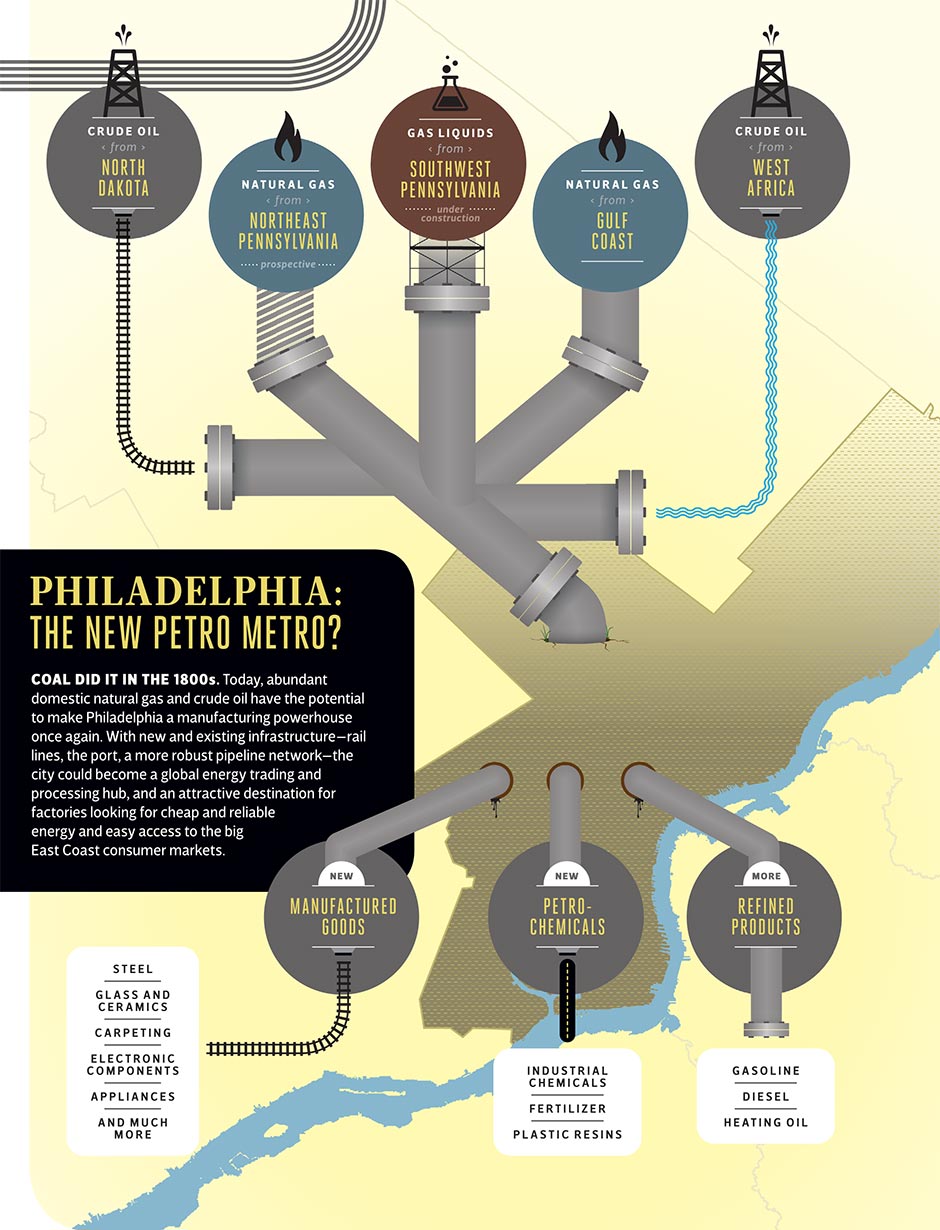

Before long, the same could be true of Philadelphia. The spoils of the Marcellus Shale gas fields will gush into the core of the city and its suburbs through broad new pipelines. Gargantuan processing facilities, built with billions of dollars of global capital, will rise like steel stalagmites along the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers. New factories — lured by the abundant low-cost energy the pipelines provide — will hire thousands of working-class residents to make plastic, steel, cement and countless consumer goods. Air pollution will increase, but so will the local GDP, as energy traders and executives fill up downtown office buildings.

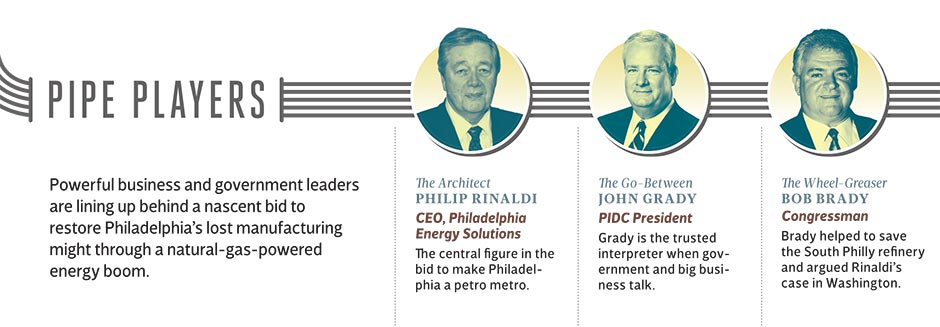

For more than a year now, talk has circulated about Philadelphia’s future as an energy hub, an idea advocated by some of the region’s most powerful business and political leaders. But the ultimate goal of their still-nascent campaign is much grander than is widely understood. Their objective is nothing less than the Workshop of the World reborn: a Philadelphia with a new natural-gas-powered economy, built atop a foundation of manufacturing might.

The scope of their ambition is at once breathtaking, inspiring — and more than a little frightening. There’s the potential here for a fundamental shift in Philadelphia’s landscape, its economy and even its basic character. And it’s a vision that, incredibly, looks to be just as plausible as it is radical.

How Philadelphia Could Become an Energy Hub

THE MAN AT THE CENTER of this campaign is Phil Rinaldi, CEO of Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES), the company that owns the sprawling South Philadelphia refinery that looms into view on the approach from the airport into Center City. Crude oil has been refined at the confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers since 1866, not long after the nation’s first oil rush began in Titusville, Pennsylvania. This is the oldest and largest working refinery on the East Coast, a 1,400-acre heap of vast structures and impossibly twisted tubes that churn out about 6.7 million gallons of gasoline a day, plus heating oil, jet fuel, and an array of other petroleum products.

The refinery’s long run looked to be at an end as recently as early 2012, when refinery operator Sunoco was planning to permanently shut the plant down if a buyer couldn’t be found. That’s when Rinaldi showed up, backed by the Carlyle Group — a massive private equity firm with $203 billion in assets worldwide — to rescue the site from what many had considered its certain demise.

I first met Rinaldi that fall. In the two years since, my mind had turned him into a larger-than-life oilman from the Deep South, with a pronounced accent and maybe cowboy boots. Actually, he’s lived most of his life in New Jersey, and he spends “as few days as possible in Houston.” Rinaldi is also accessible, soft-spoken, and an unusually effective ambassador for an industry that typically prefers to avoid the press and public when possible.

Rinaldi has made a hell of an impression on Philadelphia’s political and business establishment since coming to town. He’s a classic industrialist, the kind of guy who drags a city along with him, ready or not, like some tycoon of old. And yet he’s no John Galt. Aware that he’ll need their help, Rinaldi is carefully cultivating relationships with pivotal political figures like City Council President Darrell Clarke and Congressmen Bob Brady. (Rinaldi, who by the standards of an energy CEO was indifferent to politics in the past, hosted a fund-raiser for Brady this spring.) With the help of the Chamber of Commerce, Rinaldi has convened an “energy action team,” comprised of about 50 area executives and local officials, to advance the energy-hub agenda. And he has assiduously courted labor, with smashing success.

I was wrong about Rinaldi’s accent. But his ambition is indisputably Texas-sized. “We think there’s an opportunity here to absolutely transform the economy of Philadelphia,” he tells me in a conference room at PES headquarters on Market Street. Rinaldi has a build as ponderous as his mind is agile, with a droopy face that springs to life when he talks about the city’s industrial prospects. He looks to be in his late 60s, but he gasps in horror and refuses to answer when I ask his age. “Philadelphia, as everybody knows, it’s a meds-and-eds kind of place, and that’s great, but there was a time when it was meds and eds and manufacturing.”

In 1950, a third of all working Philadelphians labored in factories. Today, that has dwindled to just five percent, for a host of reasons too familiar to list. Modern-day job growth in Philadelphia is driven by the arts (jobs up 27 percent between 2004 and 2012), hospitality (19 percent), education (27 percent) and health care (30 percent), according to U.S. Census data. Most Philadelphians, I think, have made peace with the notion that big industry is a part of the city’s past. Philadelphia’s identity today is built on intellect rather than manufacturing, on haute cuisine instead of heavy industry.

Rinaldi flatly rejects that. “I’ve never changed. I really believe in the need for manufacturing and heavy industry. I think it’s a key for a vibrant economic society,” he says. “That’s not been a widely held view for a long time, so for a guy who does these kinds of businesses, you spend much of your life being quietly vilified by people.”

But not in Philadelphia, Rinaldi hastens to add. At least, not so far. “We have political leadership that’s supportive at really every level.”

Just as crucial as political backing, Rinaldi says, is the region’s neglected but still extant industrial infrastructure. Philadelphia was literally built for this. Back in the 1800s and early 1900s, the city’s massive manufactories — Baldwin Locomotive Works, the Cramp shipyards and many more — were powered by cheap and abundant Pennsylvania anthracite. The fuel is different today — gas and crude instead of coal — but Philadelphia’s infrastructure and geography remain just as compelling and relevant as they were 100 years ago.

Philadelphia has perhaps the best freight rail connections in the East; the port; unbeatable proximity to the nation’s largest consumer markets; and heavy industrial sites along both rivers with the zoning and acreage for guys like Rinaldi to build massive new plants. “Manufacturing in Philadelphia isn’t dead,” he argues. “It’s just in a state of suspended animation.”

But that latent infrastructure has been waiting for decades. “So what’s changed?” I ask Rinaldi.

“The whole world,” he replies.

In recent years, the American energy sector has hit a series of massive gushers: crude in the Bakken formation beneath the grasslands of North Dakota, gas in the Piney Woods of Texas and Louisiana, and, above all, the Marcellus Shale here in Pennsylvania.

So far, the Marcellus find hasn’t reverberated much in Philadelphia, apart from creating a small number of jobs and a lot of anti-fracking bumper stickers. But it’s hard to overstate the national and even global significance of the gas field in the Marcellus Shale, which is one of the two or three largest, not just in the U.S., but in the world.

Fracking, the controversial and relatively new drilling technique that blasts shale rocks with fluids at tremendous pressures in order to fracture the rocks and release the gas and oil they contain, has utterly upended the old energy world order. According to the International Energy Agency, the United States became the globe’s top producer of natural gas last year. In 2015, the U.S. is projected to become the second largest producer of oil, trailing only Saudi Arabia.

American energy independence, that great unicorn that presidents since Richard Nixon have yearned to capture, is now legitimately within reach, with potentially profound implications not just for the nation, but for the local economy.

But as long as the massive reserves of the Marcellus Shale have to flow through Texas and Louisiana to reach Philadelphia, these developments mean little to the city. Without direct access to the Marcellus boom, Philadelphia has little more going for it than Baltimore, Pittsburgh, or any other Eastern city with an industrial infrastructure. “None of it,” Rinaldi says of Philadelphia’s energy-fueled future, “is possible without the pipeline.”

PIPELINES ARE BOTH ubiquitous and reliably controversial. Gas distribution lines, the sort that feed your stove and boiler, run beneath most residential streets, forgotten by all until something goes wrong. But even big transmission lines are far more prevalent than is commonly understood, traversing some 300,000 miles nationwide.

I was surprised, upon consulting a map, to find a hazardous-liquids pipeline just a few blocks from my house in Delaware County, part of a network that winds from the Delta Airlines-owned refinery in Trainer through dense suburban neighborhoods like Drexel Hill before crossing into Philadelphia, running near the Temple University Hospital complex, and terminating at a holding facility in the city’s Hunting Park neighborhood.

For Rinaldi’s vision to have an honest chance of becoming reality, the region needs at least two more pipelines. One is already under construction, a project dubbed Mariner East. Sunoco Logistics is repurposing an 83-year-old petroleum pipeline that, when finished, will pump 70,000 barrels per day of natural-gas liquids like propane and ethane — which is a crucial building block for the petrochemical industry — from Marcellus Shale fields in Southwest Pennsylvania to a Sunoco site in Marcus Hook.

The second pipeline — the one Rinaldi champions — would be different. Instead of natural-gas liquids, it would transport dry natural gas, the stuff that fires domestic water heaters and, on a far more massive scale, co-generation facilities that can power energy hogs like data centers and steel factories. His pipeline would be huge — as big as 42 inches in diameter, which is as wide as gas pipelines get. If built, it could triple the flow of gas into the city, industry insiders say.

Rinaldi has plenty of PES uses in mind for the gas. He wants to build a new ammonia plant at the refinery, and probably a smallish gas-fired power plant as well. He’d use the hydrogen found in natural gas to enhance petroleum products he already makes at the refinery. And he’d readily invest — possibly in concert with other investors — at least $1 billion to do all that, and probably a lot more.

But even those massive projects would consume just a fraction of the gas a 42-inch pipeline would supply. So who would use the rest? PGW might buy some, if the price is right. If PGW is privatized, the new operator might buy even more. And there could be other major customers within the city who would consume more gas if more were available.

But Rinaldi imagines that the ultimate consumers of all that gas are factories and petrochemical firms that have little or no presence in the region. Yet. His pitch boils down to Build it and they will come. Rinaldi argues that the region’s inherent industrial appeal — its infrastructure, its proximity to major markets — will prove irresistible to: a) manufacturers who burn a lot of gas or use a lot of power when making their products; and b) petrochemical companies that use gas and its by-products as raw materials. Once, that is, a roomy new pipeline creates a physical link between the city and the global wonder that is the Marcellus Shale.

It’s a highly unconventional, perhaps unprecedented, way to build a pipeline. For both regulatory and business reasons, pipelines are customarily built to meet existing demand, not imagined future use. Rinaldi basically wants to construct one on spec.

That means finding investors — he mentioned the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, among others — willing to help pay for a pipeline now in hopes that demand will spike and the capacity can be sold off later. As pipelines go, this one would be pretty short — 100 miles or so. But it would traverse densely populated areas, which could drive up costs dramatically. It could cost a billion dollars or more.

Can it be built Rinaldi’s way? “I am skeptical about the ‘Build it and they will come’ idea. I think it’s a big hurdle,” says Mihoko Manabe, an energy analyst and senior vice president at Moody’s. (When I share Manabe’s critique with some Rinaldi allies, they assure me they’re exploring more traditional pipeline financing approaches as well, though Rinaldi didn’t emphasize those in our conversations.)

And then there’s the matter of overcoming inevitable grassroots and political opposition to a new pipeline. Sunoco’s experience is instructive here. The Mariner East project — which is simply a repurposing of an existing pipeline, remember — has been bedeviled by community opposition, environmentalists, adverse judicial rulings, and hostile politicians at the township level.

Indeed, Rinaldi, usually so open, clams up when pressed for pipeline details like potential routes. Early on, he floated the notion of laying pipe beneath the bed of the Delaware River, which enraged environmentalists for obvious reasons. Now he’s more circumspect. When I ask him about the route, the pipeline’s size, and the viability of getting it built on spec, he replies, “We’re trying hard not to take any idea off the table.”

“ANYTHING THAT PHIL is gonna be involved in, I’m confident he is up to the task,” says Jim Savage, president of the United Steelworkers Local 10-1.

Savage represents about 750 hourly workers at the South Philadelphia refinery. And he’s not just rough around the edges; he’s jagged. When I meet him at the Steelworkers union hall, he offers me a beer (it’s noon) and tells me the interview will wait until he finishes a Marlboro menthol. His cell-phone ringtone is a Celtic punk anthem (that catchy ditty from The Departed), and his forearms are tattooed with the phrases NOTHING IS IMPOSSIBLE and PRAY FOR THE DEAD AND FIGHT LIKE HELL FOR THE LIVING. There’s a whiteboard near his desk, and across the top someone has written “Shit List,” followed by the names of PES managers who have pissed off Savage and his members.

The point is that Savage is nobody’s pawn. He’s also one of the smartest labor leaders I’ve met anywhere, with an intuitive grasp not just of employee-labor dynamics, but of politics and the broader economic conditions his members work in. And that, I think, explains why he is doing everything possible to help Rinaldi (management) succeed.

Like a lot of the workers he represents, Savage doesn’t have a college degree. But he takes home around $100,000 a year as a lead operator in the refinery’s catalytic reformer unit. He likes to tell a story about the months following the refinery’s rescue. “I wish I’d taken a camera to work every day, just to take a picture of the parking lot,” he says. “I bought a new car, and I wasn’t alone; let me tell you, that parking lot transformed. And that means some autoworker has a job, and the lady at the credit union has a job, the guy who makes the fancy brochures has a job. That’s how this thing works, right?”

Well, that’s how it used to work. When manufacturing was king, there was decent work for the working class. “I graduated high school in 1982. The two largest employers in the country in 1982 were G.M. and U.S. Steel,” Savage tells me. (Actually it was G.M. and AT&T, but his point stands.) “When my son graduated in 2009, the two biggest employers were Walmart and Kelly Services, which is a temp agency.” Savage spreads his fingers, then closes them into rugged balls. “So in literally one generation, that’s what happened to opportunity in this country for people like me and my family and my co-workers.”

For Philadelphia — with its 26.3 percent poverty rate, a feeble tax base, a school system unable to prepare most of its children for high-skilled jobs — more quality manufacturing jobs would be a huge boon. “If you want to isolate the worst employment problem in the city, it’s most profound in the lower-skilled or undereducated population, which historically was the manufacturing workforce,” says Alan Greenberger, the city’s deputy mayor for economic development.

Jobs in the refining and petrochemical businesses pay exceptionally well. Savage’s lowest-paid members earn $22 an hour, with generous benefits, and most make far more. “You can raise a family on that,” says Savage. “You can send a kid to school and have a mortgage and some disposable income to go out to dinner, to buy flowers for your wife.”

The trick is creating more jobs like that, which won’t be particularly easy even if the pipeline gets built. People in the energy and petrochemical businesses are fond of talking about molecules. Natural gas is, essentially, methane, and methane is just one atom of carbon and four atoms of hydrogen. Burn methane and you’ve got heat, and power.

Which is great. But if the goal is economic development and job creation, collecting methane and moving it around doesn’t accomplish all that much. True, there are a lot of construction jobs in building a pipeline. But those are temporary gigs, with little lasting economic impact. Big energy facilities, like a refinery or power plant, can cost billions to erect but typically employ well under 1,000 workers.

This helps explains why the Marcellus Shale — an energy boom of global consequence — has had such an underwhelming impact on Pennsylvania’s economy. Statewide in 2012, only 14,900 workers had jobs directly in the oil and gas extraction and logistics businesses, according to census data. The state’s arts and leisure sector, meanwhile, employed more than 100,000.

Right now, Pennsylvania is the Angola of the American energy economy — a province exploited for its rich natural resources while the real money gets made where the pipelines converge along the Gulf Coast. To change that anemic economic-development dynamic, Pennsylvania must lure companies to the state who can do more with the molecules than stuff them in a pipeline. “This is the core issue,” says Fernando Musa, CEO of Braskem America, a major Brazil-based petrochemical company. “Are Pennsylvania and Philadelphia just exporters of the molecules, or is there a way to manipulate the molecules here, to add value, to create new products?”

Musa spends most of his time at the company’s U.S. headquarters in Philadelphia. But he calls me from an office in São Paulo, Brazil, where Braskem is a household name. The firm is one of the largest petrochemical companies in the world, with 36 industrial plants and gross revenue of $22 billion.

Braskem is also a compelling example of the jobs and economic activity that can be generated by manipulating those molecules. At its facility in Marcus Hook, Braskem uses a chemical called propylene (which is made from petroleum) to make plastic resins that end up in countless consumer products, from Tupperware to carpeting. In all, Braskem employs about 250 people at its Marcus Hook plant and its Center City headquarters.

“That’s what people at Braskem and other companies are thinking about: How do we connect the dots so the molecules don’t just travel back to Houston or Louisiana?” says Musa.

If more Braskems locate in Philadelphia, that means more high-paying jobs at more massive petrochemical plants. It means more managers, traders and lawyers in downtown office buildings. And — fingers crossed — it means companies that use Braskem’s plastics to make diapers, upholstery, electronics casings and much more will contemplate moving their own factories to the region, to cut down on transportation costs, ease logistical tangles, get their goods to the East Coast market quickly, and take advantage of all that cheap Marcellus gas.

BEFORE NATURAL GAS emerged as the ostensible savior of Philadelphia’s (and America’s) manufacturing sector, green energy was supposed to power an industrial revival. Before that, the Internet was supposed to make Philadelphia into the logistical beating heart of digital retail. And before that, there was surely another Next Big Thing that was destined to revive Philadelphia’s factories and economy, only it didn’t. So is the hype over natural gas really any different?

Boris Brevnov thinks so. At age 29, Brevnov was running Russia’s Unified Energy System (which is exactly as big a deal as it sounds), with a dedicated line to the Kremlin on his desk. He was bounced from the position in a political dustup, eventually landed at Enron, then went on to specialize in mergers and acquisitions for a couple of big energy companies. Now Brevnov has put together a group of investors, under the name Liberty Energy Trust, that wants to buy the Philadelphia Gas Works. When I ask him if the energy-hub talk is realistic or boosterish fantasy, he tells me, in a pronounced Russian accent, “You have unique infrastructure in place. You have the largest LNG [liquefied natural gas] storage facility on the East Coast, you have a big logistics hub, you have the ports, and you have Marcellus, the biggest field anywhere, and it’s 100 miles away.”

Brevnov’s partner, Charlie Ryan, concurs. “I can invest anywhere, and so can Boris,” says Ryan, who runs a Russia-focused asset management company. “We absolutely believe it’s genuine. The reality is that it’s going to require a lot of investment and some intelligent public policy, but it’s not only possible; it’s a huge opportunity.”

The Players Behind Philly’s Energy Future

I find it pretty convincing that figures like Brevnov and Ryan see opportunity in Philadelphia, of all places. And they’re clearly not alone. Indeed, Brevnov’s Liberty Energy Trust has come up short, so far at least, in its bid to buy PGW. The leading bidder is UIL Holdings Corp., of Connecticut, which is willing to plunk down $1.86 billion for the utility. (The sale has not yet been approved by City Council.) Nobody is spending that kind of money for the privilege of heating Philadelphia homes. The bids were plumped up by the moneymaking potential of PGW’s physical assets — principally its liquefied natural gas plant and holding tanks. Investors look at that infrastructure, imagine a new pipeline, and figure they can make a tidy profit liquefying natural gas for use as a fuel for cargo ships or trucking fleets. Another group of investors paid $140 million to build a crude-oil-by-train facility in Eddystone that opened this year, doubling down on the bet that Bakken crude from the Dakotan oil fields can be a long-term supply for East Coast refineries.

And then there’s Rinaldi and the Carlyle Group, one of the world’s most powerful and well-resourced private equity firms, with staggering political juice worldwide. Past Carlyle affiliates include advisers George H.W. Bush, former Secretary of State James A. Baker III, and former British prime minister John Major, who ran the firm’s European division for several years (and that’s just a sampling of former senior government officials to earn Carlyle paychecks). The Carlyle Group has clout with the Obama administration as well. According to a Reuters report, Bob Brady, acting on Carlyle’s behalf, asked for and received Vice President Joe Biden’s help in establishing new EPA guidelines that relaxed requirements for the inclusion of biofuels (such as corn ethanol) in gasoline.

Brady, who declined to be interviewed for this story, probably considered it a favor to a major district employer (and it surely didn’t hurt that Rinaldi had hosted a fund-raiser). For Carlyle, it was a matter of protecting its large and growing investment in the Philadelphia refinery. Indeed, the fact that Carlyle took on the risk of the refinery, spent huge sums of money on improvements, and is prepared to up that bet by a billion or more if a pipeline is built says plenty about the city’s prospects as an energy hub. So does Carlyle’s purchase, for $4.9 billion, of DuPont’s performance coating division, which is now headquartered in Philadelphia. That kind of investment goes a long way toward proving that Philadelphia’s energy and manufacturing prospects aren’t simply the stuff of boosters at the Chamber of Commerce.

Still, marketing has its place, and Rinaldi and the Philadelphia Energy Action Team plan to begin their pitch in earnest on December 5th, when they’ll host “representatives of every important chemical and high-energy-use company from Europe and Asia,” Rinaldi says. There may be another big announcement made before then. William R. Sasso, chairman of Stradley Ronon and a longtime Republican power player, is a political sherpa for the energy-hub effort. He says “a major European company” (he won’t say which one) is “80 percent” there on a big new project in the region, one that would cost $300 million to $400 million and generate about 600 jobs. “That’s significant, and it’s real,” Sasso says. “There are others that will follow suit.”

I looked for skeptics. There aren’t many. Timothy Kelsey, co-director of Penn State’s Center for Economic and Community Development and a balanced voice on the economic impact of the Marcellus, says, “Philadelphia very clearly has advantages over other areas relative to this type of activity.” Christina Simeone of PennFuture, an environmentalist who largely dreads the prospect of Philadelphia as an energy hub, says a pipeline would “be a game changer not just for Philadelphia’s energy economics, but for the state.” Manabe, the Moody’s analyst who is skeptical of Rinaldi’s pipeline tactics, nonetheless thinks his broader strategy is “a very interesting concept.” She says, “Logistically, location-wise, Philadelphia is in a good spot — that’s what made Philadelphia such a great city in the time of the Industrial Revolution.”

One of the few industry experts I found who pumped the brakes even a little was Musa, the Braskem America CEO. He sees two major hurdles. One is that the refinery sites — where new petrochemical plants would probably locate — are awfully close to heavily populated areas, which could make it politically difficult to get them built. Second, Musa says, is the massive head start the Gulf Coast has on Philadelphia. “It’s a complex supply chain,” he says, “and you have to lure companies to fill each step in that chain.”

Still, even with those obstacles, Musa thinks Philadelphia will get there, in time. “The base is there. It will happen,” he says. “The question is, does this happen over 20 or 30 years, or in five or 10?”

But there’s an even more basic question: Is this what we really want?

SHORTLY BEFORE 1 A.M. on January 20, 2014, a 101-car freight train rumbled over the Schuylkill Arsenal Rail Bridge laden with crude oil from the Bakken fields of North Dakota, destined for the South Philadelphia refinery. If you spend much time in Center City or West Philadelphia, you’ve likely seen the oil trains. Like giant mobile Tootsie Rolls with a highly explosive filling, the mile-long trains cruise slowly through the core of Drexel’s campus and past Penn’s ball fields, or, on another route, alongside joggers and toddlers in strollers beside the Schuylkill River trail. At least two trains a day traverse Philadelphia, and more are coming all the time, as the PES refinery ramps up production. Already Rinaldi’s refinery is the single largest customer of Bakken crude, and the vast majority of that oil is traveling by train.

That January night, the last seven cars on the train derailed. When morning dawned, commuters saw the cars listing precariously above the river. To call it a narrowly averted disaster is an understatement. The cars could have toppled onto the Expressway, exploding in a massive fireball. They could have crashed into the Schuylkill, spilling thousands of gallons of crude into the city’s most scenic waterway.

“The fact that they’ve packed this highly volatile material in substandard cars that roll right through city communities — it’s just intolerable,” says Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, of the steady rumbling of oil trains in Philadelphia. “What will it take for us to figure that out? Forty-seven people burned alive and half the town destroyed?” This isn’t just empty fear-mongering. The oil trains — which began rolling on such a massive scale only after PES bought the refinery — present a real and serious risk. In July 2013, a runaway oil train slammed into a nightclub and killed 47 people in the Québec town of Lac-Mégantic. And while the oil trains represent probably the biggest new risk of Philadelphia’s emerging energy economy, they’re hardly the sole one. The refinery itself is a highly dangerous place, with a history of deadly accidents and unplanned releases of toxic material. (New pipelines, on the other hand, have an excellent safety record. It’s aging gas distribution lines, like those owned by PGW, that are worth worrying about.)

But even if accidents can be avoided, there are significant downsides to Rinaldi’s vision. One is the risk that the city itself — both its residents and its tax base — will get the short end. Abatements and tax incentives could suck up a lot of the potential public revenue a petrochemical boom could create. And Savage readily acknowledges that his membership “doesn’t look like the city we work in.” About 95 percent of the refinery’s hourly workforce is male, a “large majority” is white, and only about 15 percent live within the city, he says. That dynamic will have to change dramatically if the energy and manufacturing boom Rinaldi imagines is to have the economic impact many Philadelphia officials hope for.

Then there are the inevitable environmental consequences. Natural gas — though much cleaner than coal — is a fossil fuel, and a contributor to global warming. Locally, the biggest worry is probably air quality. The Philadelphia area already has some of the worst air in the nation, trailing only the big metros of car-crazed Southern California and Fairbanks, Alaska, where the locals burn a lot of wood. The biggest single reason the region’s air quality is so rotten is the South Philadelphia refinery. Rinaldi’s shop generates more than 73 percent of the toxic air emissions in Philadelphia, and 31 percent of all toxic emissions in the five-county region.

If the refinery expands, if petrochemical companies flock to Philadelphia and its suburbs to use natural gas from newly constructed pipelines, there will be more air pollution — perhaps a lot. “When you start to talk about a fertilizer plant, an LNG processing facility — these are really nasty plants that would be located in an already stressed urban environment near low-income communities,” says Christina Simeone of PennFuture. “Is this the future we want for Philadelphia?”

Before I interviewed Rinaldi, a PES spokeswoman showed me a heavily photoshopped aerial image of the refinery’s oil train unloader, with the stubby brown weed cover tinted golf-course green and the black tanker cars turned blue. “I really want the cars to pop,” she told me. “But it’s too much, right? Not realistic.” It seemed an inauspicious start. There’s a long history of whitewashing risk in the extraction and energy businesses.

But when I raise the safety and environmental objections with Rinaldi, he’s smart enough to take them seriously. Indeed, PES generally gets superb marks from city officials and frontline workers like Savage for its focus on minimizing dangers. “I think a lot about the incident in January,” Rinaldi tells me. “Really awful. If you wanted to pick a bad place for a problem — it’s hard to think of a worse one.”

Then Rinaldi rallies. He talks up investments in track safety and rail safety reforms. He reminds me that hazardous materials have been traveling by train for a very long time. Rinaldi and his allies, including many in local government, think this is an argument they can win. “On a clear day, I can see the cooling tower of the Limerick nuclear plant,” says Greenberger, the deputy mayor. “Energy production comes with an inherent set of risks and an inherent set of environmental issues. We need to be precise about what those are and how we manage them.”

I DOUBT, THOUGH, THAT it’s possible to manage all the fallout of Philadelphia’s potential evolution into Houston on the Schuylkill. The worst-case scenario, I think, isn’t that Rinaldi’s vision fails utterly, but rather that it’s only half-realized. The pipelines get built. But instead of powering a local manufacturing boom — and creating tens of thousands of permanent, high-paying jobs — the gas is liquefied and exported, or minimally processed into plastics and industrial chemicals that are shipped off to other destinations where they’re made into consumer goods. In that scenario, Philadelphia absorbs almost all the environmental downsides, all the risks associated with large, dangerous petrochemical plants, with only a fraction of the job growth and economic impact boosters are hoping for.

And if Rinaldi’s plan is fully realized, and the petrochemical boom leads to rapid manufacturing growth, Philadelphia will be forever changed — economically and physically, yes, but also in the collective imagination. Cities tend to take their identities from what they do best. Los Angeles is sprawling, vapid and chirpy, like the media. San Francisco is smart, rich, and a bit uncertain how to handle all that money, like the tech industry. Washington is powerful and excruciatingly self-absorbed, like most politicians.

A century ago, Philadelphia’s identity was just as clear; the city was industrious, if a bit complacent. Ever since the factories left, Philadelphia’s image has been less certain. The best things the city has going for it — eds and meds, a graceful and entertaining downtown, a surfeit of personality — have yet to gel into a clear, modern reputation. How will that nascent new identity be altered by a petrochemical boom centered just two miles from Rittenhouse Square? The bet here is that we’ll soon find out, ready or not.

Originally published as “Pipe Dreams” in the October 2014 issue of Philadelphia magazine.