Bruce Robinson: Neumann-Goretti’s Turnaround Artist

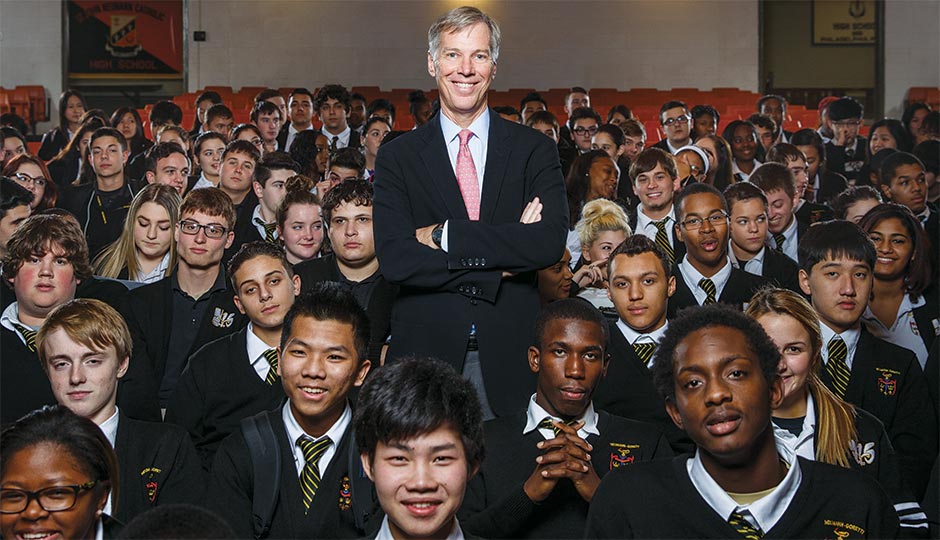

Bruce Robinson wants Neumann-Goretti to be a preeminent college-prep school. Photograph by Gene Smirnov

Inside a near-empty auditorium at Saints John Neumann and Maria Goretti High School in South Philly, roughly 100 adults are sitting in a sea of burnt-red seats beneath a statue of the outstretched Christ. Standing before the group, Bruce Robinson no doubt hopes a divine presence is watching over him, too.

Robinson, Neumann-Goretti’s new president, is in the middle of a town hall meeting with the school’s parents, and he’s getting an earful from some of them.

“People treat us like we send our kids to Graterford,” one mother says. Adds another mom (who happens to be the principal of a nearby parish elementary school): “There’s a perception out there that this school is going to close in a year or two.”

The parents’ anxiety is palpable — and understandable. Over the past decade, enrollment at Neumann-Goretti has dropped from almost 1,300 students to 500. The school, once a mainstay for second- and third-generation immigrant families who lived near the Italian Market, is the only remaining vestige of parochial high-school education south of City Hall — and it’s dying a slow death.

That’s where Robinson comes in. “When I started here, I had at least a dozen people ask me if I was brought in to close the school,” he tells the parents. He’s determined to set the record straight: “I was brought in to turn this school around.”

Robinson — a lean 59-year-old who looks a bit like a well-kempt Steve Buscemi — is a top-button-buttoned kind of guy, dressed in black slacks and a purple tie, facing the parents of a student body made up of more than one-third minority students. Half the families at the school qualify for financial aid, and most of them live in South Philly. Robinson, in contrast, is a wealthy lifelong businessman who has paid for his four kids’ college educations, lives on the Main Line, and has just leased an apartment in Center City. He’s also never worked in education before, and wasn’t even a Catholic until late November, when he completed an expedited adult confirmation process. Six months into the job, he still speaks like he’s auditioning for an episode of Shark Tank. (Example: “What we’re doing here is fine-tuning our value proposition.”) He’s convened this town hall, eight days before Thanksgiving, in order to unveil a radical business plan he believes can rejuvenate the foundering school.

Before the start of next school year, Robinson says, Neumann-Goretti will complete an inside-out overhaul of its curriculum, transforming itself from a traditional Catholic high school to a bona fide college prep school with a special focus on business, innovation and entrepreneurship. Among the items he’s outlined: quadrupling the AP course offerings; outfitting each student with an iPad to improve individualized learning; installing a 20-week internship program with Center City employers that will offset almost half the yearly tuition of participating students; and creating a brand-new “lab for entrepreneurship and innovation” — a school within a school for a select group of bright minds who want to launch the next Snapchat or robotic drone. Robinson is even toying with the idea of a new name: Neumann-Goretti Academy. And he plans to do all of this without raising tuition.

“We want to be the premium co-educational college prep school in the Philadelphia area,” Robinson tells the parents. “This is the comeback story, pure and simple.”

If his plan succeeds, Robinson may have built a blueprint for resuscitating parochial high schools throughout Philly. If it fails, he’s just another businessman without a quick fix, and there will be plenty of hubris to pick up off the floor.

THE EXTERIOR OF Neumann-Goretti looks a little like a prison: a drab brick building at 10th and Moore that’s surrounded by barbed-wire fencing. “If you were from Center City and came to visit the school and saw barbed wire on it, where would you think you’re sending your kid?” Robinson asks when I first meet him inside his modest presidential office. “I can’t have them thinking it’s a correctional institution.”

The aesthetic is no less spartan inside. Religious idols and dress-code fliers dot the hallways, which were designed for plumper enrollment. Although Robinson has redesigned Neumann-Goretti’s website and redecorated his office with student artwork, the school looks about the same as when it opened in 2004, with the merger between all-male Neumann — previously located 16 blocks farther south on Moore — and the all-female Goretti. Both schools had South Philly roots dating back decades. (Neumann was founded in the ’30s; Goretti, in the ’50s.) “Countless teens met at Neumann/Goretti mixers, later married and ultimately sent their children and grandchildren off to repeat the same life cycle,” Philadelphia Weekly wrote in an article at the time of the merger. “Both high schools were as much about perpetuating a way of life as they were about education.”

But over the past quarter century, as the neighborhood became more multicultural and the nation more agnostic, even the consolidated Neumann-Goretti fell victim to the larger forces plaguing the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. Three years ago, facing depleted enrollments and an estimated $6 million operating deficit across its schools, the Archdiocese announced it was closing four of its 17 high schools and closing or merging 45 of its 156 elementary schools. Some teachers still ask why Neumann-Goretti wasn’t on that list; Robinson believes it was spared solely for its symbolic importance in South Philly.

That summer, instead of closing all the schools (more than 30 elementary schools were shuttered), the Catholic Church in Philadelphia made an unprecedented move: It handed control of its high schools to a private nonprofit, Faith in the Future. The five-year agreement with the Archdiocese went something like this: Faith in the Future would cover any operating deficits for special-education schools and parochial high schools, including Neumann-Goretti, in exchange for the authority to guide the strategic direction of each school. Faith in the Future increased fund-raising from $12 million per year before the takeover to $19.6 million two years later, stabilized enrollment declines, and installed new leaders who embody the data-driven mind-set of its board of directors (composed of current and former CEOs from companies such as Tasty Baking, LifeShield and Cigna).

Robinson fits right in with that fraternity. He earned his B.S. in business administration at Drexel in 1978, then his master’s in taxation four years later. Out of college, he spent eight years as a certified public accountant, followed by 25 years as an executive in private-sector real estate development. As the president of GMH Military Housing, based in Newtown Square, he swooped into the military-housing sector when President Clinton signed the Military Housing Privatization Initiative in 1996, allowing private companies to build, renovate and maintain housing on military bases. “What we were able to do is take thousand-dollar-a-month stipends from soldiers and then go to Wall Street and use that income to raise billions of dollars to build and renovate housing,” Robinson says. He hopes to apply a similar approach at Neumann-Goretti, providing a higher-quality product without inflating the price.

In 2008, four years after an initial public stock offering, GMH was bought out by a British construction behemoth, making Robinson a multimillionaire. Six years later, the entrepreneur was twiddling his thumbs at a consulting job in the suburbs, looking for new inspiration, when he received an email from real estate magnate and Faith in the Future board member Brian O’Neill, who was seeking a business leader to run Neumann-Goretti. Despite a career in business and his flight to the ’burbs, Robinson says he’s always felt a pull to give back to Philadelphia. “This is a chance for me to use experiences that I’ve accumulated over 35 years in the business world and try to put them to good use,” he says. Raised in the Mayfair section of the city, Robinson is the son of a public-school principal — so it’s only right that he finally ended up in education. “The big joke is that I’m in the family business,” he says.

NEUMANN-GORETTI WILL require more than a million dollars to pay for all the changes Robinson wants: training teachers to integrate SAT prep into classes; hiring professors to teach college courses at the high school; purchasing technology for the entrepreneurship lab. Robinson is coy about how he’ll come up with the funding by September, but smart money says the benefactor of the new-look school could be Faith in the Future.

“What Bruce is trying to help people understand is that he wants to radically differentiate Neumann-Goretti,” says Faith in the Future CEO Samuel Casey Carter. As Carter sees it, Neumann-Goretti will be a test case for a new parochial-school model within the Archdiocese: a network of specialized high schools, overseen by Faith in the Future, that would collectively resemble a university model — a school for business and entrepreneurship at Neumann-Goretti, a center for art and design elsewhere, another school hosting an engineering program. “You’re going to see all of our schools increasingly emphasize both their core programs and their program accents.”

Carter was previously the president of National Heritage Academies, a prominent for-profit charter chain. Unabashedly, he compares Faith in the Future’s idea of an umbrella system to that of charter stars KIPP and Mastery. Each school will supply its own unique identity while tapping into Faith in the Future’s branding, fund-raising capacity, and expertise in strategic planning. “We create the better together, and they create the individual excellence,” Carter says. “And yes, this is right out of the charter-school playbook.”

Ironically, when charter schools burst onto the education scene in the ’90s, many of them stole the calling cards of Catholic education — high standards, uniforms, discipline — which in turn stole away parochial students. “I mean, if the Catholic schools had patented it, there would be a trade war going on right now,” says Sean Kennedy, a former fellow at the Lexington Institute who has written influential white papers on national Catholic education. In 1961, more than 250,000 children in the Philly region attended parochial schools, which were then free; now, local high schools cost as much as $7,700 a year for non-Catholics, and total enrollment in Archdiocesan schools is down to 57,500. According to Kennedy, the only way for parochial schools to survive the wave of free charters is by practicing what Faith in the Future preaches — rebranding themselves as providers of a better-quality product, using “the charter-school mentality and treating people like customers,” he says. “They need to change, and if they don’t, they’ll be dead like the dodo.”

AS BRUCE ROBINSON IS walking me through his pitch to potential investors for the forthcoming academy (a painstakingly extensive 31-page PowerPoint), he’s speaking in fluent dweeb. That’s when I realize he has a bit of a Mitt Romney problem. As he tosses out terms like “innovative learning,” “partnership with a flagship” and the all-important “value proposition,” it’s easy to see why this might impress some of his business brethren; it’s harder to imagine a middle-class family ponying up $8,000 a year for a values-based education that’s framed like a stock analysis.

And yet Robinson’s corporate lexicon is symptomatic of the way education reform is trending in this city. Over the past several years, the heavily indebted Philadelphia School District has embraced a “portfolio model” — a term derived from Wall Street — that scrutinizes our schools like stocks, using market principles to allocate resources to successful schools and, conversely, to target underperforming schools for closure. A prominent supporter of that model is the Philadelphia School Partnership, which over the past four years has doled out more than $35 million — to parochial, charter and traditional public schools — to boost innovative solutions to the schools crisis. (Whether PSP’s money amounts to subversion of the public schools or is its saving grace is a hot debate.) The head of PSP, Mark Gleason, drew national headlines in April for comments he made in support of the portfolio model: “You keep dumping the losers and over time you create a higher bar for what we expect of our schools.”

PSP also happens to be one of Faith in the Future’s donors. It’s not a stretch to see Robinson as an adjunct of the same corporate-minded reform agenda that both Gleason and Faith in the Future endorse. Robinson espouses private-sector ideas and isn’t shy about criticizing the lack of strategic thinking from his predecessors at Neumann-Goretti. “What’s the definition of insanity? You do the same thing over and over again, expecting a different result,” he says. “The business world is more black-and-white. It’s more cutthroat, and if something isn’t to your liking, you can change it immediately.”

Robinson’s turnaround is a bold solution to an acute problem. Time will tell whether Neumann-Goretti 2.0 can compete with charters and overcome the disarray within the Archdiocese’s parish-school system. But this much is known: The Archdiocese — short on money and ideas — is praying that private expertise can save its schools. When an institution is shedding 80 students a year, a shock to the system is the only way to keep faith alive and the doors open. Ultimately, if the turnaround succeeds, it’s irrelevant whether a priest or a businessman drew up the Hail Mary. Says Robinson: “I think that once we get people through the door, they’re going to like what they see.”

Originally published as “The Turnaround Artist” in the February 2015 issue of Philadelphia magazine.